The largest monument in Europe, carved from a monolithic rock, is located on the border of Romania and Serbia. The sculpture of the Dacian king Decebalus, famous for his frequent raids on the Roman Empire, took ten years to build; the work was completed in 2004. Twelve mountaineering sculptors worked on the sculpture, 40 meters high and 25 meters wide. The place was not chosen by chance: it was here, in the narrow canyon of the Danube, that the Roman emperor Trajan in 105 won the final victory over the army of Dacia, building a bridge across the river. Decebalus, who did not want to surrender, committed suicide by piercing himself with a sword.

More than a ton of dynamite was used to create the composition. The rock that served as the basis for the monumental bust of the Dacian king rises above the majestic Djerdap Canyon (in Romanian - Porţile de Fier). The statue of Decebalus, which cost more than a million dollars to create, was commissioned by Romanian businessman and historian Joseph Constantin Dragan.

You can see the monumental sculpture of the Dacian king Decebalus from the shore, but the best option is a boat ride along the Djerdap Canyon. Such trips along the Danube start from Orsova; excursions are available from May to October.

How to get there

The sculpture of the Dacian commander Decebalus is located 17 kilometers southwest of the city of Orsova, on the border of Romania and Serbia. The monument rises above the canyon, called Djerdap in Serbian and Porţile de Fier (Iron Gate) in Romanian. If you are traveling around Romania, you can get to the attraction via the DN57 highway, which runs along the picturesque bank of the Danube.

If your path runs along, then you can see the statue from the opposite bank of the river in good and clear weather. Route 25-1 runs along the Danube, a short distance from the high rocky banks. Leaving the car by the road, you can walk to the shore through the forest (about 200-300 meters); the monument will be located behind the bridge. The distance to the nearest town of Tekiya (Tekiјa) is about 11 kilometers.

Domitian's war with the Dacians ended in peace in 89. The emperor was satisfied with the formal expression of submission on the part of the Dacian king Decebalus and celebrated a triumph in honor of the victorious end of the military campaign. Peace with the Dacians allowed Domitian to secure the empire's borders on the lower Danube and transfer his army to another theater of war. One can only guess how long the peace on the Dacian border would have lasted if Domitian had not been killed in 96 by the conspirators. The new emperor Trajan did not continue the policies of his predecessor and began to prepare for the final solution to the Dacian issue.

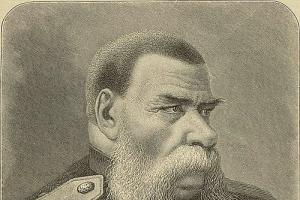

Best Emperor

Trajan was born on September 18, 53. His first step into public life was serving under his father's command in Syria. In 84 he became praetor, in 86 legate of the VII Double Legion stationed in Tarraconian Spain. In 89, by order of Domitian, he led his legion into Upper Germania, whose governor, Antony Saturninus, declared himself emperor. The uprising was suppressed even before his arrival, but Trajan managed to take part in the campaign against the Germans on the Rhine and Danube.

As a reward for his successes, in 91 he received the consulate, and then the governorship, first in the province of Lower Moesia or Pannonia, and then in Upper Germany. Here, in the late autumn of 97, he first received news of his adoption by Emperor Nerva, and then, after Nerva’s death at the end of January 98, of his inheritance of supreme power in the empire. Trajan was in no hurry to leave for Rome. He spent almost a year and a half in Germany, where he was engaged in the reconstruction of the border. Here Trajan's policy was focused on armed containment and maintaining peace with the Germans.

Trajan was a tall man and had a good physique. He had great physical strength and incredible endurance. His face was characterized by a concentrated expression, full of dignity and enhanced by premature gray hair.

On the contrary, the situation on the lower Danube gave him serious fears. Before leaving for Rome, in 99 he undertook an inspection trip to Pannonia and Moesia, as a result of which he decided to start a war against the Dacians.

Cause of war and preparation for it

Roman coins printed in anticipation of the war depicted Mars the Avenger, which was intended to depict an impending campaign of revenge against an enemy who had invaded Roman territory several times over the past fifty years and was responsible for the deaths of two military leaders and a huge number of ordinary soldiers. The peace concluded with the Dacians in 89 immediately after the death of Domitian began to be perceived by his successor as unfavorable and even shameful for Rome. The dependence of the Dacians established by the terms of the treaty was not too great; their military assistance during the subsequent conflicts with the Marcomanni and Sarmatians was insignificant. Decebalus used the cash subsidy that Rome agreed to pay him, as well as the help of Roman military specialists, to build up his own forces.

It should be taken into account, however, that these statements were partly the result of a course of deliberate discrediting of the foreign policy of his predecessor, which was carried out by Trajan. They were also caused by fear of the growing power of the Dacians. The official point of view was voiced by Pliny the Younger in his Panegyric to Trajan, delivered around the year 100:

“So, they became proud and threw off the yoke of subordination and already tried to fight with us not for their liberation, but for the enslavement of us, did not conclude a truce except on equal terms, and, in order to borrow our laws, imposed theirs on us.”

Trajan addresses the soldiers. The Emperor is the most frequently depicted character in the reliefs decorating Trajan's Column. In total, he is depicted on it 59 times.

Trajan addresses the soldiers. The Emperor is the most frequently depicted character in the reliefs decorating Trajan's Column. In total, he is depicted on it 59 times.

The main base for the attack force's attack was Upper Moesia. During the years 100–101, 12 legions from various provinces were gathered in its capital Viminacium (Kostolac). The basis of the army was the Upper Moesian IV Flavius and VII Claudius legions, which were joined by the V Macedonian and I Italian legions from Lower Moesia. Probably, the I Auxiliary, X, XIII and XIV Double, as well as the XV Apollo legions from Pannonia were also involved in full during the campaign. Vexillations of the VI Victorious and VIII Augustus legions were brought up from the Rhine. Even from distant Britain, vexillations of the XX Valerius the Victorious Legion arrived. In the winter of 102, vexillations of the XII Lightning and XVI Flavius legions from Cappadocia were used to eliminate the Sarmatian invasion on the lower Danube.

In addition to the legions, a large corps of auxiliary troops took part in the war, no less than 19 cavalry units, 63 auxiliary and mixed cohorts, as well as contingents provided by dependent rulers and allies of Rome. The Moorish cavalry under the command of their leader Lusius Quiet, eastern archers, and detachments of German allies arrived. The total number of troops assembled exceeded 100,000.

Roman ships on the Danube, relief from Trajan's Column

Roman ships on the Danube, relief from Trajan's Column

For the convenience of supplying this mass of people, old communication routes were reconstructed and new ones were laid. In the year 100, in the Iron Gate (Djerdap Gorge) on the modern border of Serbia and Romania, a road was cut into the rock, which was a hanging balcony. To ensure smooth navigation of ships on the section of the Danube between the cities of Gradac and Karatash, which was replete with dangerous rapids and rapids, a canal 3 km long and 11–35 m wide was laid.

I Dacian War 101 – 102

Trajan left Rome on March 25, 101. It is assumed that he first arrived in Ancona, from there he crossed by sea to Dalmatia and then continued his journey along the Morava to Viminacium. With his arrival, the army crossed the Danube in two columns on pre-built pontoon bridges. The western column, crossing at Lederata (Palanca), was commanded by Trajan himself. The eastern one, under the command of the governor of Lower Moesia, Mania Liberius Maximus, was crossed at Dierna (Orshova).

The emperor's army moved along the same route that Tettius Julian used in 88. A few accidentally preserved words from Trajan’s marching message - “from there we entered Berzobis (Berzovia), and then to Aizis (Fyrlyug)”– are an accurate topographical reference of the route. The army of Liberius Maximus advanced along the valley of the Cherna River through the Teregover Pass to meet it. In the Tibisca (Karansebash) area, both columns of the Roman army successfully united.

Then they followed the valley of the Bistra River in the direction of Tap (Virgo), where the main forces of Decebalus were located. As during the previous campaign, a decisive battle took place here. The Romans were victorious again, but the cost was great. Decebalus managed to retreat with the remnants of his forces to the mountains of Orastia. Leaving Liberius Maximus with half the army to besiege the fortress of Tapa, Trajan himself rushed in pursuit of the retreating. His goal was the Dacian capital Sarmisegethusa, but the early winter that began that year made the continuation of the campaign impossible.

Dacian War of Trajan, routes of the main campaigns of the Romans

Dacian War of Trajan, routes of the main campaigns of the Romans

Trajan returned to spend the winter across the Danube, leaving 4 legions in the captured part of the country and intending to continue the campaign in the spring of next year. Meanwhile, Decebalus organized a second front against the Romans. At the end of the winter of 102, his allies the Roxolani and Aorsi, under the leadership of their kings Susag and Inismea, as well as the Dacians, Bastarnae and Getae, crossed the frozen Danube. They swept away the barrier put up against them by Liberius Maximus and broke into the territory of Lower Moesia. Trajan had to send additional forces to support him, primarily cavalry units from his army. Part of the army was transported on ships of the Danube flotilla.

Thanks to timely assistance, the barbarian detachments were blocked on both sides and completely defeated in a series of bloody battles. The largest of them occurred near the modern Romanian city of Adamiklissi. Its scale is evidenced by the sheer number of Roman losses, amounting to almost 4 thousand people. In connection with this battle, Roman wounded were depicted for the first and last time in the battle scenes of Trajan's Column. Perhaps the episode mentioned by Cassius Dio refers precisely to this event, when in order to bandage the wounded, Trajan ordered his own clothes to be torn into bandages.

Subsequently, in 109, in honor of this victory, a monumental trophy of Trajan was erected in the form of a mound on a stepped base with a diameter of 38 m and a height of 40 m. The crown of the monument was surrounded by a frieze decorated with 54 metopes with images of battle scenes and figures of captive barbarians.

Scene of the battle between the Romans and the Dacians on Trajan's Column

Scene of the battle between the Romans and the Dacians on Trajan's Column

In the spring of 102, the war in Dacia resumed. The Romans again moved towards Sarmizegetusa, advancing in two columns. One part of them, under the command of Trajan himself, relying on previously created bases, advanced from the west through Tapi. The other, under the command of Liberius Maximus, from the south along the valley of the Olt River and the Turnu Rosu pass went to Apul. As evidenced by the reliefs of Trajan's Column, soldiers continued to pave roads and build bridges and towers along the way. Decebalus sent his envoys to the Roman camp, offering to enter into negotiations, but the summit meeting never took place.

The reliefs of the Column show the Romans storming some kind of fortress, it must be Apulus. Numerous trophies were taken during the offensive. In one of the mountain fortresses, weapons and a banner were discovered that were captured by the Dacians during the defeat of the army of Cornelius Fuscus in 86. Liberius Maximus managed to capture the sister of King Decebalus. Somewhere between Apul and Sarmizegetusa another great battle took place, again ending in victory for the Romans.

The Dacians laid down their arms and begged the Roman emperor for mercy. The figure standing at full height depicts the Dacian king Decebalus. On the right the Dacians are demolishing their fortifications

The Dacians laid down their arms and begged the Roman emperor for mercy. The figure standing at full height depicts the Dacian king Decebalus. On the right the Dacians are demolishing their fortifications

Having lost hope of victory and fearing for his capital, Decebalus finally sued for peace. His ambassadors arrived at a Roman military camp set up in the vicinity of Sarmizegetusa. The king was ordered to hand over weapons, defectors and prisoners, tear down fortifications, pay a huge indemnity and take an oath of allegiance to Rome. All conditions, despite their severity, were accepted. Decebalus' envoys were sent to Rome to appear before the Senate. Trajan returned to Rome, where he celebrated his triumph and received the solemn title “Dacian” from the Senate.

Interwar years

Immediately after the end of the First Dacian War, Roman troops began strengthening camps and strongholds around Dacia and building communications in the border zone on the Lower Danube. Brick marks, inscriptions and coins on the left bank of the Danube reveal the presence of the I Auxiliary, III Flavius the Fortunate and XIII Dual legions.

VII Claudius' legion in 103 - 105 was busy at Drobeta (Kostol) with the construction of a large stone bridge across the Danube. The bridge was built according to the design of Apollodorus of Damascus, a brilliant engineer whose works also include Trajan's Forum and Trajan's Column in Rome. The bridge over the Danube became a real miracle of engineering of its time. The length of the bridge was 1.2 km, it was erected on 20 stone pillars, each about 50 m high and 18–20 m wide. The bridge spans had an arched structure and were made of wooden beams. Images of this wonder of the world were presented on reliefs of Trajan's Column and in a large series of minted Roman coins.

Trajan makes sacrifices before starting his campaign in Dacia. Behind as a background is a bridge across the Danube, built in 103 - 105 by Apollodorus of Damascus

Trajan makes sacrifices before starting his campaign in Dacia. Behind as a background is a bridge across the Danube, built in 103 - 105 by Apollodorus of Damascus

Despite the defeat and capitulation, Decebalus did not consider himself completely defeated. When surrendering the weapons, he managed to conceal a significant part of them, and also continued to accept Roman defectors. The clause of the agreement providing for the demolition of the fortifications was completely ignored by him. In addition, the king sought to start negotiations with Rome’s opponents. In particular, in the capital of the province of Bithynia, Callidromus, a former slave of Liberius Maximus, who in 102 was captured by the Sarmatians and presented to Decebalus, was identified. He sent Callidromus to the Parthian king Pacorus II to encourage the Parthians to attack the Roman borders. On the way back, he managed to escape and so he ended up in his native Nicomedia, where he was exposed and sent under escort to Trajan.

The emperor's patience finally ran out in the winter of 104, when Decebalus attacked the Sarmatian-Yazyges living along the Tisza. Unlike their relatives the Roxolani, the Iazyges were Roman allies during the previous war. Decebalus took revenge on them for supporting Rome and took away part of their territory, which directly violated the terms of the peace treaty. In light of these events, at the beginning of 105, the Senate declared war on him.

II Dacian War 105 – 106

Decebalus tried to take the initiative into his own hands by launching a preemptive strike against the Roman garrisons left on the left bank of the Danube. The Romans were ready and managed to repel all attacks. The attack on the bridge was also unsuccessful. On June 6, 105, Trajan left the capital for the theater of military operations. By this time, the army stationed on the border with Dacia had increased to 16 legions. The I Minerva and XI Claudius legions from the Rhine arrived on the Danube, as well as the newly created II Trajan legion. With the arrival of Trajan, the legions crossed the Danube across the bridge at Drobeta and moved north in several columns. Their goal was again the Dacian capital Sarmisegethusa, which, contrary to the treaty, Decebalus hastened to strengthen.

Dacians lay siege to a Roman fortification

Dacians lay siege to a Roman fortification

The details of the war are not fully understood, because its presentation in the sources, as well as the scenes depicted on Trajan’s Column, represent an incomplete and unreliable reflection of the events. The war seems to have taken an extremely violent form, involving the killing of prisoners on both sides and the destruction of Dacian dwellings.

Decebalus captured a high-ranking military man, Gnaeus Pinarius Aemilius Pompeius Longinus, consul-suffect of 90, governor of Upper Moesia in 93–96 and Pannonia in 98. After the end of the first war with the Dacians, he commanded the Roman troops on the left bank of the Danube. Decebalus promised to return the prisoner if Trajan would withdraw his troops beyond the Danube. While the emperor was considering his answer, Pompey Longinus took poison, which he obtained through a loyal freedman. He sent the freedman himself with a letter to Trajan. Having discovered what had happened, Decebalus offered to hand over the body of Longinus in exchange for the return of the freedman, but Trajan refused, considering the preservation of his life more significant than the burial of the dead.

Battle of the Romans with the Dacians

Battle of the Romans with the Dacians

Sarmisegethusa was surrounded and fell after a fierce assault. The Dacian leaders chose to commit suicide so as not to fall into the hands of the enemy. One of the scenes from Trajan's Column shows them taking a cup of poison in a circle. The golden treasury of Decebalus fell into the hands of the Romans. The money was hidden at the bottom of a cave dug in the bed of the Sargetia River flowing near the capital. The prisoners who performed this work were all killed, but one of the king’s close associates revealed the secret.

Decebalus himself fled from the capital and, with a few associates, retreated to the mountains in the east of the country. Here he continued his resistance until he died in 106. One of the reliefs of the Column depicts the persecution and death of the Dacian king. The retinue accompanying him was killed by Roman horsemen. Seeing no salvation, Decebalus pierced himself with a sword.

Suicide scene of Decebalus, relief of Trajan's Column

Suicide scene of Decebalus, relief of Trajan's Column

In 1965, a funeral stele and epitaph belonging to Tiberius Claudius Maximus was found near Philippi in Macedonia. The inscription indicates that it was he who captured Decebalus and gave his severed head to Trajan in the fortress of Ronistore in the territory of modern Transylvania. The head of Decebalus was sent to Rome and here thrown on the Haemonian steps at the foot of the Capitol.

Results of the war

As a result of the Roman conquest, Dacia was devastated. Cities and fortresses lay in ruins, the country's wealth was stolen, livestock was slaughtered, fields were burned. A significant part of the country's population died, thousands of survivors were forced to leave their homeland. About half a million Dacians were captured and sold into slavery. To populate the newly conquered lands, Trajan had to resettle there many colonists from among the Romanized population of the Balkan and eastern provinces. A significant part of the new population were army veterans and members of their families.

The Romans capture the Dacians

The Romans capture the Dacians

Huge booty was captured during the war. According to John Lida, it amounted to 5 million pounds of gold (2 thousand tons) and 10 million pounds of silver (4 thousand tons). In value terms, this was equivalent to 30 years of imperial income! Trajan donated about 50 million sesterces to the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, in addition, every Roman citizen received 2000 sesterces as a gift from him. Using Dacian wealth, the emperor was able to completely resolve financial problems and make generous distributions to soldiers in anticipation of new campaigns being prepared against Parthia.

Literature:

- Kruglikova, I.T. Dacia during the era of Roman occupation / I.T. Kruglikova. – M., 1955.

- Parfenov V.N. Domitian and Decebalus: an unrealized version of the development of Roman-Dacian relations // Ancient World and Archeology. - Vol. 12. ― Saratov, 2006. ― P. 215–227.

- Kolosovskaya Yu.K. Rome and the world of tribes on the Danube. I-IV centuries AD, Moscow, 2000

- Zlatkovskaya T.D. Moesia in the 1st – 2nd centuries AD. M., 1951.

- Rubtsov S. M. Legions of Rome on the Lower Danube: military history of the Roman-Dacian wars (end of the 1st - beginning of the 2nd century AD). – St. Petersburg: Petersburg Oriental Studies, 2003. – 256 p.

- Chaplygina, N.A. Romans on the Danube (I–III centuries AD) / N.A. Chaplygin. – Chisinau, 1990, – 187 p.

- Salmon E.T. Trajan's Conquest of Dacia // Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 67 (1936), pp. 83–105

- Bennet J. Trajan, Optimus Princeps. A Life and Times. ― London-New York: Routledge, 2006. ― 317 p.

- Speidel M. A. Bellicosissimus princeps // Traian. Ein Kaiser der Superlative am Beginn einer Umbruchszeit? Nünnerich-Asmuss A. (Hrsg.). - Mainz a. R.: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 2002. - S. 23–40.

- Strobel K. Die Untersuchungen zu den Dakerkriegen Trajans. ― Bonn: Rudolf Habelt, 1984. ― 284 p.

Dacia from Burebista to Decebalus. Connections between the Dacians and the Romans

Dacian rulers. After the overthrow of Burebista, power briefly passed to Deceneus. Then the throne was inherited, as Jordanes says, by Komozik, who had as much power as his predecessor. The same historian notes that “after this one also left human affairs, King Corillus reigned over the Goths, and he ruled his tribe in Dacia for forty years.”

The name Corilla is not confirmed by other sources. It is possible that Jordanes confused him with King Scorilon, who is mentioned in later monuments and who was a contemporary of Nero. On the other hand, it is possible that after Komozik, the throne in Sarmizegetuz was actually occupied by a king who ruled for a very long time. Other sources name a certain Cotizone ( Cotiso), who reigned in Dacia in the last third of the 1st century. BC e. and at the beginning of the next century. Thus, in one of Horace’s odes, written in 29 BC. e., it is said that “the army of the Dacian Cotizon was defeated” (III, 8, 18). In turn, Suetonius mentions Cotisone when talking about the conflict between Octavian and Mark Antony. In the oldest manuscripts of the works of Suetonius, the spelling is preserved Cosoni (Cosini) Getarum regi. Numerous treasures of gold were found in the vicinity of the capital of the Dacian kingdom. /29/ coins with the inscription "Koson" in Greek letters. Therefore, it is possible that King Koson is the same Kotizon mentioned in the sources. Moreover, Cotiso is again mentioned as an enemy of Rome in the context of the events of 11–12 AD. n. e. His power extended to the mountainous part of Dacia, which may coincide with those mountains where the capital of Dacia, Sarmizegetusa, was located (Florus, 11, 28, 18–19). This Coson-Kotizon ruled for a very long time (about four decades), which corresponds to the data of Jordanes, who, however, could well have confused the name of the Dacian king with the name of another, later ruler.

After the era of Augustus, ancient authors no longer mention the Dacian kings, since most of the first half of the 1st century. n. e. and the first decades of the second half of this century were a relatively calm period, without major clashes between the Dacians and the Romans. Therefore, it should be borne in mind that the names of several rulers who followed each other may simply not have reached us.

During the time of Nero, King Skorilon is mentioned. The dates of his life are unknown, but it is likely that the throne was inherited by his brother Duras, who attacked Moesia in the winter of 85/86. Soon after this, according to Cassius Dio, “Duras, who had previously ruled, voluntarily transferred power to Decebalus, since he was a skilled commander...” (LXVII, 6, 1).

All the rulers of Dacia up to the wars with Trajan were known to contemporaries, mainly because of the conflicts that arose between the Dacians and the Romans. However, there were relatively calm periods when tensions eased and Dacia's economy boomed thanks to trade exchanges with the Roman Empire.

Daco-Roman relations. As already mentioned, after the conclusion of an alliance between Burebista and Pompey, Caesar became an enemy of the Dacians and planned a great campaign against them. The assassination of Caesar delayed its start, but Octavian did not abandon this plan, and after the Pannonian War of 35–33. BC e. the city of Segestes became the base for preparing a military campaign against the Dacians (Appian, Illyricum, 22, 65–66). However, the decisive clash with the Dacians was again postponed due to the outbreak of the Civil War.

In 29 BC. e. The Dacians (under the leadership of Coson-Cotizon) and the Bastarni attacked the Roman possessions south of the Danube, after /30/ what the governor of Macedonia, Marcus Licinius Crassus, did in 29–28. two punitive campaigns. The Dacians and Bastarnae were defeated, and the Romans headed to Dobruja. Supported by the king of the Getae, Rol, who owned the regions in the south of Dobruja, Crassus defeated first Dapix, taking possession of Central Dobruja, and then over Zirax, whose possessions were in the north of this region. After the campaign of Crassus, peace was established in the eastern part of the Lower Danube for some time.

By the end of the 1st century. BC e. and at the beginning of the next century the theater of war between the Dacians and the Romans shifted to the west and southwest of Dacia. During the war that the Romans waged against the Pannonian tribes in 13-11. BC e., the Dacians attacked the western regions of the Lower Danube. Marcus Vinicius repelled the attack and pursued the enemy all the way to Mures. Due to frequent Dacian raids, especially on the western “front”, at the beginning of the 1st century. n. e. Aelius Catus made a campaign in the area north of the Danube (probably in Banat), from where he resettled 50 thousand Dacians in the area south of the Danube. At the same time, in 11–12. BC e., the Dacians of Coson-Cotizon suffered a new defeat. Florus (II, 28, 18–19) narrates these facts and tells how these predatory raids took place. “The life of the Dacians was closely connected with the mountains. From there, under the leadership of King Cotizon, they descended and devastated the neighboring regions as soon as the ice bound the Danube and connected its banks. Emperor Augustus decided to put an end to these people, who were not easy to reach. He sent Lentulus there, who pushed them to the opposite bank, and left garrisons on this bank. Thus, then (11–12) the Dacians were not defeated, but only driven back and scattered.” Traces of these collisions have been found by archaeologists. Dacian fortifications on the left bank of the Danube, at the Iron Gate (Lyubkova, Pescari, Divic), were burned at the beginning of the 1st century. n. e. Some were later restored, but then destroyed again during the Daco-Roman wars at the end of the 1st - beginning of the 2nd century.

After the formation of the province of Moesia and the construction of a Roman fortress on the right bank of the Danube (probably during the reign of Tiberius), the Romans were able to effectively defend their possessions south of the Danube. As a result, the number of Dacian raids decreased sharply. Until the wars of Domitian and Trajan, there were no serious conflicts between the Dacians and Romans, with rare exceptions. /31/

In 66 or 67, the governor of Moesia, Titus Plautius Silvanus Aelian, resettled over 100 thousand “Transdanubian inhabitants” in the area south of the Danube, as can be learned from the inscription dedicated to him on a tombstone discovered in Tibur. This new “colonization” of the right bank was carried out so that those forcibly resettled would cultivate the land and pay tribute. Soon after these events, taking advantage of the unrest that arose in Rome in connection with the death of Nero, and the fact that the fortress was left unprotected, the Dacians attacked Moesia in the first months of 69. Tacitus wrote: “The Dacian tribe was also indignant; they were never truly loyal to Rome, and after the troops left Moesia they decided that now they had absolutely nothing to fear. At first they remained calm and only watched what was happening, but when the war flared up throughout Italy and the armies, one after another, began to be drawn into the fight, the Dacians captured the winter camps of foot cohorts and cavalry units, captured both banks of the Danube and were about to attack the camps of the legions "( History, III, 46, 2). The situation was saved by Mutian, the governor of Syria, whose troops were quickly heading to Italy from the eastern regions. Having learned about the Dacian invasion, he hastened to restore the previous situation along the entire course of the Danube. This Dacian raid foreshadowed a series of conflicts during the reign of Domitian. The Dacian invasion of Moesia during the reign of Duras (winter 85/86) was even more devastating and became a kind of prelude to those events that ultimately led to the conquest of Dacia by the Romans.

Despite constant clashes, throughout most of this period economic relations between the Dacians and Romans developed along an upward trend. During the reign of Burebista, products from Roman workshops came to Dacia; Of these, the most famous are bronze vessels from the late period of the republic. In the last quarter of the 1st century. BC e. in a number of settlements, jewelry and metal parts for clothing of the Roman type appeared. But a particularly large number of products produced in the Roman Empire (bronze and ceramic vessels, glass and iron products, jewelry, mainly bronze, etc.) penetrated into Dacia during the 1st century. n. e., which is explained by the relatively peaceful situation in the period after /32/ the reign of Augustus, as well as the formation of the border provinces of Pannonia and Moesia.

Products from the Roman Empire spread throughout Dacia. But their particular concentration is observed in a number of economic and trade centers (for example, in large settlements in the Siret Valley in the South Carpathian region, in Ocnita in Oltenia, in Piatra Craivius in Transylvania), mainly in fortresses and settlements around the capital of the Dacian kingdom. In Dacia in the 1st century. n. e. Roman artisans were already working. The technologies used in a number of metalworking workshops and the products of these workshops clearly indicate where the craftsmen came from. Finally, due to the integration of Dacia into the Mediterranean economy, the Dacian kings began to accurately copy Roman coins, abandoning the coinage characteristic of the period preceding the establishment of the kingdom of Burebista. Two coin workshops (one discovered on the site of the fortress in Tiliška, and the other in Sarmizegetusa Regia itself), as well as a number of finds in other settlements, indicate that the Dacian kings reproduced silver Roman denarii with great accuracy. These coins were minted until the conquest of Dacia by the Romans, and it is no coincidence that about 30 thousand such coins were found on the territory of Ancient Dacia, much more than in other “barbarian” regions neighboring the Roman Empire.

From the book Empire - II [with illustrations] author20. Linguistic connections between Russia and Egypt in the Middle Ages 20. 1. What alphabet did the Copts - the inhabitants of Egypt - use? The Copts are the Christian inhabitants of medieval Egypt. They, according to Scaligerian history, gave the country their name: Copt - Gypt - Egypt. And then we find out

From the book Reconstruction of World History [text only] author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich8.12.7. THE CLOSE RELATIONS BETWEEN “ANCIENT” AMERICA AND “ANCIENT” EURASIA ARE WELL KNOWN. BUT THEY DID NOT BEGAN IN “ANTIQUE”, BUT ONLY IN THE XIV-XV CENTURIES Modern historical science has accumulated a lot of evidence about the close connection between the “ancient” Mayan cultures in America and the “ancient”

From the book New Chronology of Egypt - II [with illustrations] author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich9.21. Connections between ancient Egypt and Horde Russia The astronomical dating of the Egyptian zodiacs presented in this book - as well as numerous traces of Christian symbolism in ancient Egyptian art - clearly show that Ancient Egypt was medieval

From the book Rus' and Rome. Colonization of America by Russia-Horde in the 15th–16th centuries author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich18. The close connections between “ancient” America and “ancient” Eurasia are well known. But they began not in “antiquity,” but in the 14th–15th centuries. Modern historians have accumulated a lot of evidence about the close connection between the “ancient” Mayan cultures in America and the “ancient » European cultures and

From the book Neither Fear nor Hope. Chronicle of World War II through the eyes of a German general. 1940-1945 author Zenger Frido vonCONNECTIONS BETWEEN THE TWO GENERAL STAFFS Since March 1942, the Joint Anglo-American Headquarters began operating in Washington. The American Joint Chiefs of Staff was strengthened by representatives of a similar British committee. The last one by then

From the book History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages author Gregorovius Ferdinand2. Henry IV besieges Rome for the third time (1082-1083). - Capture of Leonina. -Gregory VII in the Castle of St. Angel. - Henry is negotiating with the Romans. - Dad's inflexibility. - Jordan of Capua swears allegiance to the king. - Desiderius is a mediator in concluding peace. - Henry's treaty with

From the book Barbarian Invasions on Europe: the German Onslaught by Musset LucienV. Was there an ideological confrontation between the barbarians and the Romans? Ancient historiography portrays barbarians only in black terms: they bring chaos or destruction and are incapable of creation. Is this stamp confirmed by the events of the 5th and 6th centuries? Did it move

From the book Legions of Rome on the Lower Danube: Military history of the Roman-Dacian wars (end of the 1st - beginning of the 2nd century AD) author Rubtsov Sergey MikhailovichChapter 3 The army of Decebalus and his allies

From the book Book 2. The Rise of the Kingdom [Empire. Where did Marco Polo actually travel? Who are the Italian Etruscans? Ancient Egypt. Scandinavia. Rus'-Horde n author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich14. Linguistic connections between Russia and African Egypt in the Middle Ages 14.1. What alphabet did the Copts use - the inhabitants of Egypt? The Copts are the CHRISTIAN inhabitants of medieval Egypt. They, according to Scaligerian history, gave the country their name: Copt = Gypt = Egypt. And here we are

From the book Ancient East and Asia author Mironov Vladimir BorisovichTies between Russia and India In Russia, interest in India arose a long time ago. But first we should make a small digression, giving (of course, in the most general terms) a picture of the settlement and movement of Indo-European tribes across the vast expanses of Eurasia. Today they say more often

From the book History of Armenia author Khorenatsi Movses77 About the peace between the Persians and the Romans and about the arrangement of affairs by Artashir in Armenia during the years of anarchy But Probus, who came to reign in Greece, made peace with Artashir and divided our country, marking the borders with ditches. Artashir, having taken over the Naharar tribe,

From the book World History. Volume 2. Bronze Age author Badak Alexander NikolaevichConnections between the South Siberian and Chinese tribes The culture of the eastern part of the territory occupied by the tribes of the Andronovo culture at the end of the 2nd millennium BC. e. began to differ so sharply from the culture of Western territory that this forced historians to distinguish

From the book Book 2. Conquest of America by Russia-Horde [Biblical Rus'. The Beginning of American Civilizations. Biblical Noah and medieval Columbus. Revolt of the Reformation. Dilapidated author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich22. Close connections between “ancient” America and “ancient” Eurasia are well known. But they did not begin in “antiquity,” but only in the 14th–15th centuries. Modern history has accumulated much evidence of a close connection between the “ancient” Mayan cultures in America and the “ancient » European cultures and

From the book Ancient Zodiacs of Egypt and Europe. Dating 2003–2004 [New chronology of Egypt, part 2] author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich5.2. Connections between Ancient Egypt and Horde Russia The astronomical dating of the Egyptian zodiacs presented in this book, as well as numerous traces of Christian symbolism in ancient Egyptian art, clearly show that Ancient Egypt was a MEDIEVAL

From the book The Battle for Syria. From Babylon to ISIS author Shirokorad Alexander Borisovich From the book God of War author Nosovsky Gleb Vladimirovich3.8. Old connections between the Nile and the Volga Let us now turn to the very interesting work of the Egyptian historian Amin al-Kholi. In the middle of the last century, he wrote a book based on materials from medieval Arab chronicles. The book is called: “Connections between the Nile and the Volga in

Beginning of reign

Suicide of Decebalus as depicted on Trajan's Column

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.

See what “Decebalus” is in other dictionaries:

- (Decebalus) (? 106), leader of the Dacians from 87. In 89, after a successful war with the Romans, he achieved peace, according to which Rome had to pay annual subsidies to the Dacians; the Dacian wars with Rome in 101-102 and 105-106 ended with the subjugation of the Dacians to Rome and... ... encyclopedic Dictionary

Decebălus, Δεκεβαλος, actually Doipaneus, so that Decebalus is a common name and means king or prince of the Dacians, ruled over the Dacian tribes and with his invasion of the province of Mssia provoked the campaign of Domitian against himself. Tac. Agr. 41.… … Real Dictionary of Classical Antiquities

- (Decebalus) (died 106), king of the Dacians (See Dacians) from 87. In 89, after a successful war against the Romans under Emperor Domitian, D. concluded a peace under which the Romans agreed to pay annual subsidies and provide the Dacians with Roman artisans ... Great Soviet Encyclopedia

- (Decebalus) king of the Dacians. In 86 AD, D. invaded Mysia, defeated the Roman governor Oppius Sabinus and took possession of most of this province. Emperor Domitian, despite the victory won by his general Julian at Tanya, had to... ... Encyclopedic Dictionary F.A. Brockhaus and I.A. Ephron

- (Decebalus) (d. 106) king of the Dacians, who united numerous people under his rule. Dacian tribes. A stubborn opponent of Rome (the Romans fought with D. twice under Domitian and Trajan). Created an army trained and armed for Rome. manners. In the fight against Rome... ... Soviet historical encyclopedia

Decebalus- see Ducky. (I.A. Lisovy, K.A. Revyako. The ancient world in terms, names and titles: Dictionary reference book on the history and culture of Ancient Greece and Rome / Scientific editor. A.I. Nemirovsky. 3rd ed. Mn: Belarus , 2001) ... Ancient world. Dictionary-reference book.

Decebalus- (d. 106) king of the Dacians, ed. numerous people under their authority. Dacian tribes. A stubborn opponent of Rome (the Romans fought with D. twice under Domitian and Trajan). Created an army, trained. and weapons to Rome manners. In the fight against Rome the prisoner tried. unions... Ancient world. encyclopedic Dictionary

Decebalus- (Decebalus), the last prominent Dacian king, who in 85 86 invaded Moesia and threatened Rome. state (in 101 106 Dacia was conquered by Trajan). With great foresight, using the help of the Greek. and Rome specialists., D. conducted... ... Dictionary of Antiquity

Decebalus- name of the human family, origin... Spelling dictionary of Ukrainian language

- (d. 106) leader of the Dacians from 87. In 89, after a successful war with the Romans, he achieved peace, according to which Rome had to pay annual subsidies to the Dacians; the Dacian wars with Rome in 101-102 and 105-106 ended with the subjugation of the Dacians to Rome and the suicide of Decebalus... Big Encyclopedic Dictionary

Statue of Decebalus (Decebel) on the Danube River, Romania. This is "the biggest face in Europe." This face belongs to the Dacian commander Decebalus, reaches a height of 40 meters and is the largest sculpture in Europe carved from a monolithic rock. Fans of antiquities will be disappointed: this statue is younger than you and me; it was built in 2004 by 12 sculptors who carved it into the rock for almost 10 years. The statue rises above the waters of the Danube and is clearly visible even from Serbia.

Here's a little history about him:

The country of the Dacians, who in ancient times inhabited the lands in the Carpathians between the Danube and Tissa rivers, was rich. Wheat, barley, flax, and hemp grew in fertile fields; Numerous herds grazed in the meadows; Gold was mined in the mountains and rivers. But little of this wealth went to the share of ordinary peasants. From generation to generation they lived in small palisaded villages, in cramped wooden or reed huts built on poles and covered with thatch or reeds. Crude clay utensils, simple wooden plows and other tools were stored here; Here they also buried the ashes of their burned ancestors...

Rich and powerful were the tribal leaders and nobility of the Dacians, who, unlike the common people, wore high felt hats. Built by the labor of the poor, their castles rose on inaccessible cliffs - high square towers, made of stone slabs, fastened with wooden beams, surrounded by a battlemented wall and ramparts. And inside these castles were stored expensive weapons, glass and bronze vessels, jewelry purchased from Greek and Roman traders in exchange for bread, leather and slaves...

At the end of the 1st century AD. e. A talented commander Decebalus appeared in Dacia. Relying on the people, dissatisfied with the dominance of the nobility, he tried to create a strong, unified state. Only by uniting could the Dacians resist the Romans, who had already captured all the areas along the left bank of the Danube. More and more Roman merchants entered Dacia. And the Roman legions usually came to the country for the merchants. It was necessary to gather all forces to defend freedom.

The war with the Romans began under Decebalus' predecessor, King Diurpanea. For a whole year there were battles between the Romans and Dacians. Finally, the Roman army pushed the Dacians beyond the Danube and began to cross over to enemy land.

It was then that Diurpaneus, not having the strength to continue the fight, transferred his power to Decebalus. The new leader, having begun negotiations to gain time, at the same time began to energetically prepare for war. He managed to temporarily force the nobility to obey and improve discipline in the army. At the same time, he convinced the neighboring tribes of the Bastarns and Roxolans to enter into an alliance with him. They went with carts, families, herds, and household belongings to settle in the lands that Decebalus promised to win for them from the Romans. He sent his envoys to many tribes dependent on Rome. Under the influence of negotiations with Decebalus, these tribes refused to provide the Romans with auxiliary cavalry, and then rebelled against Roman rule.

At the first clash with the Roman army, the Dacians won a brilliant victory. The commander of the Roman army died in battle; the camp with combat vehicles was captured; almost the entire legion and some auxiliary units were killed, and - which was considered the greatest shame for Rome - the banner of the legion fell into the hands of the enemy. In the south of Dobruja, in Adamkliss, there still stands a monument erected by the Romans in memory of those who fell in this battle, on which their names are written.

But Decebalus was unable to fully exploit the victory. The Dacian nobility weakened his army with their disobedience. And in the next battle, at Tapa, the Dacians were put to flight. The victory of the Romans opened the way for them to the Dacian capital - Sarmisegetusa. Fearing for her fate, Decebalus began to ask for peace. His brother arrived in Rome, brought weapons and prisoners captured from the Romans and, kneeling before the emperor, received the crown from his hands. So Decebalus recognized himself as dependent on the Roman state. At the cost of humiliation, he gained time and even bargained with Domitian for annual financial assistance. Rome also needed a break: for almost eight years it waged a war with the rebel German tribes.

Decebalus closely followed events, preparing for a new war. His agents operated in the Roman army, in the provinces, and among neighboring tribes. They skillfully sought out the dissatisfied, promised them shelter in Dacia and the protection of the Dacian king. He especially willingly accepted deserting Roman soldiers, artisans, builders, and mechanics who knew a lot about the construction of military vehicles and fortresses. Decebalus gradually negotiated an alliance with neighboring tribes, arguing that if they did not support him, sooner or later they themselves would become victims of the insatiable Rome. Some Slavic tribes also joined Decebalus. He tried to negotiate with distant Parthia, the eternal rival of Rome.

Trajan's Column. Rome

In Rome these actions of Decebalus were known. The government could not come to terms with the fact that a force had arisen in the neighborhood of the empire, ready to enter into an alliance with everyone who was dissatisfied with Roman rule. War became inevitable. It flared up when Trajan, a zealous defender of the interests of Roman slave owners, became emperor.

Proclaimed emperor, Trajan immediately set off for the Danube. He stayed here for almost a whole year, personally overseeing the construction of new fortresses, bridges and roads in the mountainous regions of Moesia. To the nine standing on. On the Danube he added troops to the legions, called from Germany and the East. In addition, two more new legions were recruited. In total, together with auxiliary units, there were about 200 thousand soldiers.

Finally, in the spring of 101 AD. e. The Roman army, divided into two columns, crossed the Danube. The western column was commanded by the emperor himself. He went to Tapa, on the approaches to Sarmizegetuza.

Before reaching Tapa, the Romans heard the sounds of the curved pipes of the Dacians and saw their military icons - huge dragons with wolf heads.

Before the start of the battle, one of the tribes, allies of the Dacians, sent Trajan a huge mushroom, on which it was written that the Romans must keep peace and that therefore they should retreat. But this peculiar letter did not stop Trajan. A bloody battle ensued. The Dacians, armed, in addition to bows, with curved sickle-shaped swords, were especially terrible in hand-to-hand combat. They fought with unshakable courage, despising death. Many Romans fell in this battle.

After the battle, the Roman troops had to pause their offensive. Gathering their strength, the Romans at the same time sought to instill fear in the Dacians: on the captured land they destroyed villages and took the inhabitants into slavery.

The Romans have always been famous not only as merciless conquerors, but also as deft diplomats. Now they tried to further inflame discord between the Dacian nobility and turn it against Decebalus. Every now and then, people in high felt hats appeared in Trajan’s camp and, kneeling down, assured him of their devotion and readiness to serve him.

Having recovered from the previous battle, the Romans launched a new attack on Tapa. The Dacians courageously defended each peak and retreated slowly, with stubborn battles. They went further into the mountains, taking Roman prisoners with them.

The Dacian position deteriorated sharply when unexpectedly the Roman auxiliary cavalry struck them in the rear and rushed towards Sarmizegetusa. Decebalus; trying to gain time, he began peace negotiations. But the Romans continued to advance, destroying fortress after fortress. More and more noble Dacians left Decebalus and ran over to Trajan.

The Dacian leader placed his last hope in the troops stationed at the fortress of Apulum, but here too he was defeated. The path to the capital was open. Decebalus had to agree to any terms of peace.

He himself appeared in Trajan’s tent. Throwing aside his long straight sword - a sign of royal power, he fell to his knees. Decebalus admitted defeat and asked for leniency. In his presence, the garrison of Sarmizegetusa, where the Roman camp was now set up, laid down its arms. According to the peace treaty, the Dacians agreed to surrender their weapons and military vehicles, demolish fortifications, hand over artisans and soldiers who had fled to them, no longer accept defectors, and always have friends and enemies in common with the Roman people. To monitor the fulfillment of these conditions, Roman troops temporarily remained in the country.

Dacian Wars. 2nd century AD

In order to be able to quickly transfer reinforcements to Dacia, Trajan ordered the construction of a stone bridge across the Danube near the Drobeta fortress. Many decades later, this bridge aroused the surprise and admiration of travelers. It was a kilometer long, supported by 20 stone pillars, 28 m high and 15 m wide. They were spaced 50 m apart and were connected by arches along which the flooring was made.

However, Decebalus did not consider himself completely defeated. He fulfilled all the terms of the peace treaty in order to quickly get rid of the Roman troops. But as soon as they left the country, Decebalus again ordered the rebuilding of fortresses and the construction of fighting vehicles. He hoped to surprise the Romans, taking them by surprise.

Having gathered significant forces, Decebalus in June 105 AD. e. began an assault on the Roman fortifications. At the same time, the Roman camp was captured in Sarmisegethus and the garrison was killed. However, this decisive onslaught was not crowned with success. The Dacians failed to break into Roman territory. Trajan hastily arrived with reinforcements. He was respectfully greeted by ambassadors from his Dacian supporters. Decebalus understood that this first defeat predetermined the outcome of the war. He knew that this time Trajan would not rest until he converted Dacia into a Roman province.

And again, in two columns, the Roman army reached out to Sarmisegetusa. Along the way it encountered almost no resistance. The hastily built fortresses could not defend themselves for long. The population, taking their property, went further into the mountains. But this time the capital was well prepared for defense. Bastions, towers and ditches stretched all the way to Tapa. The Dacians turned every rock and hill into a fortress. Huge reserves of food and gold were stockpiled in the city. Decebalus buried his own countless treasures in the riverbed near the very walls of the palace.

The siege of Sarmizegetusa lasted for a long time. The Roman army besieged it from the west and east, gradually closing the ring more and more closely. Siege structures were built and trenches were dug. Either the Dacians made forays, or the Romans tried to storm the city. Both sides had very large losses. More and more enemy heads were displayed on pillars in the Roman camp and in the Dacian capital.

Decebalus hoped to hold out until the winter cold, hoping that the frosts would force the Romans to lift the siege. But treason penetrated the ranks of his army. Several noble Dacians secretly promised Trajan to open the eastern gates of the capital for him. To divert attention, Trajan ordered the western army to begin an assault on the city at the appointed hour. After stubborn battles, she captured the advanced fortifications. At the same time, the traitors allowed the Romans into the city from the opposite side.

Anger and despair seized the Dacians when they saw enemies in their capital. They decided not to give the city into the hands of the victors and not to surrender alive. A burning torch was thrown into the royal palace building. Behind him, the wooden houses of Sarmizegetusa began to burn. The Dacians placed a large cauldron of poison in the main square. Hundreds of residents of the capital held out their cups for the deadly drink. Many corpses were already lying near the cauldron, but new crowds of those who preferred death to slavery were approaching. The father supported his dying son, preparing to immediately follow him. The mother brought the cup of poison to the child, and then drank it herself.

Roman cavalry attacks the rearguard of the Dacian army

To the sounds of solemn music, Trajan entered the deserted city at the head of the army. Here, among the smoking ruins and corpses of their compatriots, the noble traitors fell to their knees before him and were graciously received by the victor. One of Decebalus' closest associates told where his treasures were hidden. They were removed from the river bed and taken to Trajan's tent. This gold enriched the Roman treasury for a long time. Trajan donated 50 million sesterces to the Temple of Jupiter alone.

But the war was not over yet. Decebalus managed to lead some of the Dacians into the mountain forests. From there they continued to attack Roman troops. Step by step the Romans pressed them back. The Dacian position became almost hopeless when the Romans took the fortress of Apulum, which protected access to the northeastern, wildest part of the country. The Dacian partisans were still holding out there.

The remnants of the defeated troops gathered in the deep forest. Decebalus addressed them with his last speech. He said goodbye to his faithful companions and released them. There was no longer any hope left, and many turned to the last refuge - death. Some threw themselves on the sword, others asked their friends to save them from the shame of slavery with a blow of a dagger. Some sought refuge with neighboring tribes to begin a difficult, harsh, but free life there.

However, treason also penetrated into the last refuge of the vanquished. Some noble Dacians who followed Decebalus decided

gain the favor of Trajan by betraying his leader. After all, the emperor’s triumph will be incomplete if his once formidable enemy does not follow his chariot in chains. Notified by the traitors, the Roman troops blocked Decebalus's path to retreat. His few companions were killed, and finally, his horse fell under him, pierced by a spear. Decebalus fell to the roots of a tall spruce. Already the Roman soldiers stretched out their hands to grab him. With a quick movement, he pulled out a dagger and cut his throat. His head and right hand were delivered to the emperor and displayed before the crowded soldiers.

The war is over. Dacia, converted to a province, was included in the Roman Empire.

Rich rewards were distributed to the army from the huge Dacian booty. On the occasion of the Dacian triumph, Trajan gave a 123-day holiday in Rome. 11 thousand animals and 10 thousand gladiators took part in the games. The Senate decided to use funds taken from the spoils to erect a monument - a column - in honor of the winner. It took five years to build under the leadership of the Greek Apollodorus and has survived to this day. Its height reaches 40m. It is all covered with relief images of military events and is crowned with a statue of Trajan. The emperor's ashes were subsequently buried at the base of this column.

The conquered Dacians, like all provincials, were subject to taxes. Some of their land went to Roman colonists and veterans. Stationed in camps and fortresses throughout the country, the soldiers were tasked with maintaining order and suppressing dissatisfied movements.

But the people did not forget either their former freedom or Decebalus, who fought for it. Every now and then the country was invaded by free Dacians who had moved beyond its borders. They always met with the sympathy and support of their fellow tribesmen. When in the 3rd century. The Roman state began to weaken, and a liberation movement began in Dacia. Other tribes joined the Dacians...

Powerless to fight them, the Romans in the middle of the 3rd century. were forced to leave Dacia.

This was the first province to throw off the hated Roman yoke.