The German cipher machine was called "Riddle" not for the sake of words. There are legends surrounding the history of its capture and decoding of radio interceptions, and cinema largely contributes to this. Myths and truth about the German encoder are in our material.

It is known that the enemy's interception of messages can only be countered by their reliable protection or encryption. The history of encryption goes back centuries - one of the most famous ciphers is called the Caesar cipher. Then attempts were made to mechanize the process of encryption and decryption: the Alberti disk, created in the 60s of the 15th century by Leon Battista Alberti, the author of the Treatise on Ciphers, one of the first books on the art of encryption and decryption, has reached us.

The Enigma machine used by Germany during World War II was not unique. But it differed from similar devices adopted by other countries in its relative simplicity and widespread use: it could be used almost everywhere - both in the field and on a submarine. The history of Enigma dates back to 1917, when the Dutchman Hugo Koch received a patent for it. Her job was to replace some letters with others using rotating rollers.

We know the history of decoding the Enigma machine mainly from Hollywood blockbusters about submarines. However, these films, according to historians, have little in common with reality.

For example, the 2000 film U-571 tells the story of a secret mission by American sailors to capture an Enigma encryption machine aboard the German submarine U-571. The action takes place in 1942 in the North Atlantic. Despite the fact that the film is spectacular, the story told in it does not correspond to historical facts at all. The submarine U-571 was actually in service with Nazi Germany, but was sunk in 1944, and the Americans managed to capture the Enigma machine only at the very end of the war, and this did not play a serious role in the approach of Victory. By the way, at the end of the film the creators report historically correct facts about the capture of the encoder, but they appeared at the insistence of the film’s consultant, an Englishman by birth. On the other hand, the film's director, Jonathan Mostow, said that his film "is a work of art."

European films try to maintain historical accuracy, but there is also a share of artistic fiction in them. Michael Apted's 2001 film Enigma tells the story of mathematician Tom Jericho, who must solve the updated code of a German cipher machine in just four days. Of course, in real life it took much longer to decipher the codes. At first, this was done by the Polish cryptological service. And a group of mathematicians - Marian Rejewski, Henryk Zygalski and Jerzy Rozicki - studying disused German ciphers, found that the so-called day code, which was changed every day, consisted of the settings of the switchboard, the order of installation of the rotors, the positions of the rings and the initial settings of the rotor . This happened in 1939, even before the capture of Poland by Nazi Germany. Also, the Polish “Bureau of Ciphers,” created specifically to “fight” Enigma, had at its disposal several copies of a working machine, as well as an electromechanical Bomba machine, which consisted of six paired German devices, which helped in working with codes. It was she who later became the prototype for Bombe, the invention of Alan Turing.

The Polish side was able to transfer its developments to the British intelligence services, who organized further work to crack the “riddle”. By the way, the British first became interested in Enigma back in the mid-20s, however, they quickly abandoned the idea of deciphering the code, apparently considering that it was impossible to do so. However, with the beginning of World War II, the situation changed: largely thanks to the mysterious machine, Germany controlled half of the Atlantic and sank European convoys with food and ammunition. Under these conditions, Great Britain and other countries of the anti-Hitler coalition definitely needed to penetrate the Enigma riddle.

Sir Alistair Dennison, head of the State Code and Cipher School, which was located in the huge Bletchley Park castle 50 miles from London, conceived and carried out the secret operation Ultra, turning to talented graduates of Cambridge and Oxford, among whom was the famous cryptographer and mathematician Alan Turing . Turing's work on breaking the Enigma machine codes is the subject of the 2014 film The Imitation Game. Back in 1936, Turing developed an abstract computing "Turing machine", which can be considered a model of a computer - a device capable of solving any problem presented in the form of a program - a sequence of actions. At the code and cipher school, he headed the Hut 8 group, responsible for the cryptanalysis of German Navy communications, and developed a number of methods for breaking the German encryptor. In addition to Turing's group, 12 thousand employees worked at Bletchley Park. It was thanks to their hard work that the Enigma codes could be deciphered, but it was not possible to crack all the ciphers. For example, the Triton cipher worked successfully for about a year, and even when the “guys from Bletchley” cracked it, it did not bring the desired result, since too much time passed from the moment the encryption was intercepted until the information was transmitted to the British sailors.

The thing is that, by order of Winston Churchill, all decryption materials were received only by the heads of the intelligence services and Sir Stuart Menzies, who headed MI6. Such precautions were taken so that the Germans would not realize that the codes had been broken. At the same time, these measures did not always work, then the Germans changed the Enigma settings, after which the decryption work began anew.

The Imitation Game also touches on the topic of the relationship between British and Soviet cryptographers. Official London really was not confident in the competence of specialists from the Soviet Union, however, on the personal order of Winston Churchill, on July 24, 1941, materials with the Ultra stamp were transferred to Moscow. True, to exclude the possibility of disclosing not only the source of information, but also that Moscow would learn about the existence of Bletchley Park, all materials were disguised as intelligence information. However, the USSR learned about the work on deciphering Enigma back in 1939, and three years later, the Soviet spy John Cairncross entered the service of the State School of Codes and Ciphers, who regularly sent all the necessary information to Moscow.

Many people wonder why the USSR did not decipher the radio interceptions of the German “Riddle,” although Soviet troops captured two such devices back in 1941, and in the Battle of Stalingrad Moscow had three more devices at its disposal. According to historians, the lack of modern electronic equipment in the USSR at that time had an impact.

By the way, a special department of the Cheka, dealing with encryption and decryption, was convened in the USSR on May 5, 1921. The employees of the department had a lot of not very advertised victories, for obvious reasons - the department worked for intelligence and counterintelligence. For example, the disclosure of diplomatic codes of a number of countries already in the twenties. They also created their own cipher - the famous “Russian code”, which, as they say, no one was able to decipher.

Wars are fought with weapons. However, only weapons are not enough. The one who has the information wins! You need to receive other people's information and protect your own. This special type of struggle is ongoing.

The ancient Egyptians protected their secrets with hieroglyphic ciphers, the Romans with the Caesar cipher, the Venetians with Alberti's cipher disks. With the development of technology, the flow of information increased, and manual encryption became a serious burden, and did not provide adequate reliability. Encryption machines appeared. The most famous among them is Enigma, which became widespread in Nazi Germany. In fact, Enigma is a whole family of 60 electromechanical rotary encryption devices that worked in the first half of the 20th century in commercial structures, armies and services of many countries. A number of books and films such as the Hollywood blockbuster "Enigma" introduced us to the German military "Enigma" (Enigma Wehrmacht). She has a bad reputation because English cryptanalysts were able to read her messages, and this backfired on the Nazis.

This story contained brilliant ideas, unique technological achievements, complex military operations, disregard for human lives, courage, and betrayal. She showed how the ability to anticipate enemy actions neutralizes the brute force of a weapon.

The appearance of "Riddle"

In 1917, the Dutchman Koch patented an electric rotary encryption device for protecting commercial information. In 1918, the German Scherbius bought this patent, modified it and built the Enigma encryption machine (from the Greek ανιγμα - “riddle”). Having created the company Chiffriermaschinen AG, the businessman from Berlin began to increase demand for his not yet secret new product, exhibiting it in 1923 at the international postal congress in Bern, and a year later in Stockholm. The “riddle” was advertised in the German press, radio, and the Austrian Institute of Criminology, but there were almost no people willing to buy it - it was too expensive. Custom Enigmas went to Sweden, the Netherlands, Japan, Italy, Spain, and the USA. In 1924, the British took the car, registered it in their patent office, and their cryptographic service (Room 40) looked into its insides.

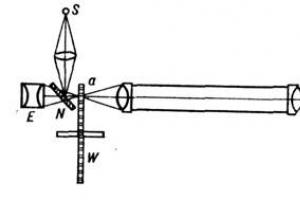

And they are simple. This is a kind of electric typewriter: a keyboard with 26 letters of the Latin alphabet, a register with 26 light bulbs with letters, a switchboard, a 4.5 volt battery, a coding system in the form of rotors with encryption disks (3-4 working ones plus 0-8 replaceable ones). The rotors are connected to each other like the gears in an odometer (car odometer). But here, unlike the odometer, the rightmost disk, when entering a letter, rotates by a variable step, the value of which is set according to a schedule. Having made a full revolution, it transfers the turn by step to the next rotor, etc. The right disk is the fastest, and the gear ratio is variable, i.e., the commutation scheme changes with each letter entered (the same letter is encrypted by differently). The rotors are marked with an alphabet, which allows you to change their initial setting according to pre-agreed rules. The highlight of the Enigma is the reflector, a statically fixed rotor, which, having received a signal from the rotating rotors, sends it back and in a 3-rotor machine the signal is converted 7 times.

The operator works like this: presses the key with the next letter of the encrypted message - the light bulb on the register lights up, corresponding (only at the moment!) to this letter - the operator, seeing the letter on the light bulb, enters it into the encryption text. He does not need to understand the encryption process; it is done completely automatically. The output is complete nonsense, which is sent as a radiogram to the addressee. It can only be read by “one of our own”, who has a synchronously configured “Enigma”, i.e., who knows which rotors and in what order are used for encryption; his machine also decrypts the message automatically, in reverse order.

“Riddle” dramatically speeded up the communication process, eliminating the use of tables, cipher notebooks, transcoding logs, long hours of painstaking work, and inevitable errors.

From a mathematical point of view, such encryption is the result of permutations that cannot be tracked without knowing the starting position of the rotors. The encryption function E of the simplest 3-rotor Enigma is expressed by the formula E = P (pi Rp-i) (pj Mp-j) (pk Lp-k)U (pk L-1 p-k) (pj M-1 p-j) ( pi R-1 p-i) P-1, where P is the patch panel, U is the reflector, L, M, R are the actions of the three rotors, the middle and left rotor are j and k rotations of M and L. After each key press, the transformation changes .

For its time, Enigma was quite simple and reliable. Its appearance did not puzzle any of Germany’s possible opponents, except Polish intelligence. The German military and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ignoring the new product, continued to work manually (ADFGX method, code books).

And then in 1923, the British Admiralty released The History of the First World War, telling the world about its advantage in that war thanks to breaking the German code. In 1914, the Russians, after sinking the German cruiser Magdeburg, fished out the corpse of an officer clutching a naval code magazine to his chest. The find was shared with their ally England.

The German military elite, having experienced shock and analyzing the course of hostilities after that incident, concluded that such a fatal leak of information should not be allowed in the future. “Enigma” immediately became in demand, was purchased en masse by the military, and disappeared from public sale. And when Hitler began to prepare a new war, the encryption miracle became a mandatory program. Increasing the security of communications, designers constantly added new elements to the machine. Even in the first 3-rotor model, each letter has 17,576 variations (26x26x26). When using 3 working rotors out of 5 included in the kit in a random order, the number of options is already 1054560. Adding a 4th working rotor complicates encryption by orders of magnitude; When using replaceable rotors, the number of options is already measured in the billions. This convinced the German military.

Blitzkrieg weapon

Enigma is just one type of electromechanical disk encoder. But here is its mass character... From 1925 until the end of World War II, about 100 thousand cars were produced.

This is the whole point: the encryption technology of other countries was piecemeal, working in the special services, behind closed doors. "Enigma" - a blitzkrieg weapon - fought in the field at levels above the division, on board a bomber, ship, submarine; was in every port, on every major railway. stations, in every SS brigade, every Gestapo headquarters. Quantity has turned into quality. The not-so-complex device became a dangerous weapon, and fighting it was fundamentally more important than intercepting individual, even very secret, but still not mass correspondence. Compact in comparison with foreign analogues, the vehicle could be quickly destroyed in case of danger.

The first - Model A - was large, heavy (65x45x35 cm, 50 kg), similar to a cash register. Model B already looked like an ordinary typewriter. The reflector appeared in 1926 on the truly portable Model C (28x34x15 cm, 12 kg). These were commercial devices with encryption without much resistance to hacking, and there was no interest in them. It appeared in 1927 with the Model D, which later worked on the railways and in occupied Eastern Europe. In 1928, Enigma G, aka Enigma I, aka “Wehrmacht Enigma” appeared; having a patch panel, it was distinguished by enhanced cryptographic resistance and worked in the ground forces and air force.

But the German Navy was the first to use Enigma. It was a 1925 Funkschlüssel C model. In 1934, the Navy adopted a naval modification of the army vehicle (Funkschlüssel M or M3). At that time, the army used only 3 rotors, and in the M3, for greater safety, you could choose 3 rotors out of 5. In 1938, 2 more rotors were added to the kit, in 1939, 1 more, so it became possible to choose 3 out of 8 rotors. And in February 1942, the German submarine fleet was equipped with a 4-rotor M4. Portability was preserved: the reflector and the 4th rotor were thinner than usual. Among the mass-produced Enigmas, the M4 was the most secure. It had a printer (Schreibmax) in the form of a remote panel in the commander's cabin, and the signalman worked with encrypted text, without access to classified data.

But there was also special, special equipment. The Abwehr (military intelligence) used a 4-rotor Enigma G. The level of encryption was so high that other German authorities could not read it. For the sake of portability (27x25x16 cm), the Abwehr abandoned the patch panel. As a result, the British managed to hack the machine's security, which greatly complicated the work of German agents in Britain. “Enigma T” (“Tirpitz machine”) was created specifically for communication with its ally Japan. With 8 rotors, reliability was very high, but the machine was hardly used. Based on the M4, they developed the M5 model with a set of 12 rotors (4 working/8 replaceable). And the M10 had a printer for open/closed texts. Both machines had another innovation - a gap-filling rotor, which greatly increased the strength of the encryption. The Army and Air Force encrypted messages in groups of 5 characters, the Navy - in groups of 4 characters. To make it more difficult to decrypt enemy interceptions, the texts contained no more than 250 characters; long ones were broken into parts and encrypted with different keys. To increase security, the text was clogged with “garbage” (“letter salad”). It was planned to rearm all types of troops with M5 and M10 in the summer of 1945, but time ran out.

"Rejewski's Bomb"

So, the neighbors were “blind” to Germany’s military preparations. The Germans' radio communication activity increased many times over, and it became impossible to decipher the interceptions. The Poles were the first to be alarmed. While keeping an eye on their dangerous neighbor, in February 1926, they suddenly could not read the encryption of the German Navy, and from July 1928, the encryption of the Reichswehr. It became clear: they switched to machine encryption. In January 29th, Warsaw customs found a “lost” parcel. Berlin's harsh request to return it attracted attention to the box. There was a commercial Enigma. Only after studying it was given to the Germans, but this did not help reveal their tricks, and they already had a reinforced version of the machine. Especially to combat Enigma, Polish military intelligence created the Cipher Bureau of the best mathematicians who spoke fluent German. They were lucky only after 4 years of marking time. Luck came in the form of an officer of the German Ministry of Defense, “bought” in 1931 by the French. Hans-Thilo Schmidt (“Agent Asche”), responsible for the destruction of outdated codes of the then 3-rotor Enigma, sold them to the French. I also got them instructions for it. The bankrupt aristocrat needed money and was offended by his homeland, which did not appreciate his services in the First World War. French and British intelligence showed no interest in this data and handed it over to their Polish allies. In 1932, the talented mathematician Marian Rejewski and his team cracked the miracle machine: “Ashe’s documents became manna from heaven: all the doors instantly opened.” France supplied the Poles with agent information until the war, and they managed to create an Enigma simulator, calling it a “bomb” (a type of ice cream popular in Poland). Its core was 6 Enigmas connected into a network, capable of sorting through all 17,576 positions of the three rotors, i.e., all possible key options, in 2 hours. Her strength was enough to open the keys of the Reichswehr and the Air Force, but she could not split the keys of the Navy. The “bombs” were made by the company AVA Wytwurnia Radiotechniczna (it was the company that reproduced the German “Enigma” in 1933 - 70 pieces!). 37 days before the start of World War II, the Poles passed on their knowledge to the allies, giving them one “bomb” each. The French, crushed by the Wehrmacht, lost their car, but the British turned theirs into a more advanced cyclometer machine, which became the main instrument of the Ultra program. This counter-Enigma program was Britain's best-kept secret. The messages decrypted here were classified as Ultra, which is higher than Top secret.

Bletchley Park: Station X

After World War I, the British cut their cryptologists. The war with the Nazis began - and all forces had to be urgently mobilized. In August 1939, a group of code-breaking specialists entered the Bletchley Park estate, 50 miles from London, under the guise of a company of hunters. Here, at the decryption center Station X, which was under the personal control of Churchill, all information from radio interception stations in Great Britain and abroad converged. The company "British Tabulating Machines" built here the first decoding machine "Turing bomb" (this was the main British cracker), the core of which was 108 electromagnetic drums. She tried all the options for the cipher key given the known structure of the message being deciphered or part of the plaintext. Each drum, rotating at a speed of 120 revolutions per minute, tested 26 letter options in one full revolution. During operation, the machine (3.0 x2.1 x0.61 m, weight 1 t) ticked like a clockwork, which confirmed its name. For the first time in history, ciphers created en masse by a machine were also solved by the machine.

"Enigma" auf U-Boot U-124

To work, it was necessary to know the physical principles of the Enigma down to the smallest detail, and the Germans constantly changed it. The British command set the task: to obtain new copies of the machine at all costs. A targeted hunt began. First, they took a Luftwaffe Enigma with a set of keys from a Junkers shot down in Norway. The Wehrmacht, smashing France, advanced so quickly that one signal company overtook its own and was captured. The Enigma collection was replenished by the army. They were dealt with quickly: Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe encryption began to appear on the table of the British headquarters almost simultaneously with the German one. The most complex one was desperately needed - the naval M3. Why? The main front for the British was the sea front. Hitler tried to strangle them with a blockade, cutting off the supply of food, raw materials, fuel, equipment, and ammunition to the island country. Its weapon was the Reich's submarine fleet. The group tactics of the “wolf packs” terrified the Anglo-Saxons, their losses were enormous. They knew about the existence of the M3: 2 rotors were captured on the submarine U-33, and instructions for it were captured on the U-13. During a commando raid on the Lofoten Islands (Norway) on board the German patrol ship "Crab" they captured 2 rotors from the M3 and keys for February, the Germans managed to drown the car. Moreover, it turned out quite by accident that there were German non-military ships sailing in the Atlantic, which had special communications on board. Thus, the Royal Navy destroyer Griffin inspected the allegedly Dutch fishing vessel Polaris off the coast of Norway. The crew, consisting of strong guys, managed to throw two bags overboard, and the British caught one of them. There were documents for the encryption device.

In addition, during the war, the international exchange of weather data ceased - and converted “fishermen” went from the Reich to the ocean. On board they had Enigma and settings for every day for 2-3 months, depending on the duration of the voyage. They regularly reported the weather and were easy to find. Special Royal Navy task forces came out to intercept the “meteorologists.” Fast destroyers literally took the enemy to task. By shooting, they tried not to sink the “German”, but to drive his crew into panic and prevent the destruction of special equipment. On May 7, 1941, the trawler Munich was intercepted, but the radio operator managed to throw the Enigma and May keys overboard. But in the captain’s safe they found the keys for June, a short-range communication code book, a coded weather log and a Navy coordinate grid. To conceal the capture, the English press wrote: “Our ships, in a battle with the German Munich, captured its crew, who abandoned the ship, sinking it.” The mining helped: the time from intercepting a message to decrypting it was reduced from 11 days to 4 hours! But the keys had expired and new ones were needed.

Captain Lemp's mistake

Surrender of the German submarine U-110 to the British. May 9, 1941

The main catch was made on May 8, 1941 during the capture of the submarine U-110 of Lieutenant Commander Julius Lemp, which was attacking convoy OV-318. After bombing U-110, the escort vessels forced her to surface. The captain of the destroyer HMS Bulldog went to ram, but, seeing that the Germans were jumping overboard in panic, he turned away in time. Having penetrated the half-submerged boat, the boarding party discovered that the team had not even tried to destroy the secret communications means. At this time, another ship picked up the surviving Germans from the water and locked them in the hold to hide what was happening. This was very important.

On the U-110 they took: a working Enigma M3, a set of rotors, keys for April-June, encryption instructions, radiograms, logs (personnel, navigation, signal, radio communications), sea charts, diagrams of minefields in the North Sea and coast of France, operating instructions for type IXB boats. The booty was compared to the victory in the Battle of Trafalgar, experts called it a “gift from heaven.” King George VI himself presented the awards to the sailors: “You deserve more, but now I can’t do it” (through the award system, German agents could have discovered the fact of the loss of the car). A subscription was taken from everyone; the capture of U-110 was not disclosed until 1958.

The gutted boat was sunk to maintain secrecy. Captain Lemp died. Interrogation of the remaining Germans revealed that they did not know about the loss of the secret. Just in case, measures were taken to disinformation, in front of the prisoners they lamented and regretted: “It was not possible to land on the boat, it suddenly sank.” For the sake of secrecy, they even coded her capture: “Operation Primrose.” Shocked by the success, First Sea Lord Pound radioed: “My heartiest congratulations. Your flower is of rare beauty.”

Trophies from U-110 brought a lot of benefits. Having received fresh information, the Bletchley Park hackers began regularly reading the communications between the headquarters of the Reich submarine forces and boats in the ocean, splitting most of the messages protected by the Hydra code. This helped break other Navy codes: “Neptune” (for heavy ships), “Zuyd” and “Medusa” (for the Mediterranean Sea), etc. It was possible to defeat the German network of submarine reconnaissance and supply vessels (“cash cows”) in the Atlantic ). The operational intelligence center learned the details of the Germans' coastal navigation, mining schemes for coastal waters, the timing of submarine raids, etc. Sea convoys began to bypass the “wolf packs”: from June to August, the “Doenitz wolves” found only 4% of convoys in the Atlantic, from September until December - 18%. But the Germans, believing that U-110 had taken its secret into the abyss, did not change the communication system. Admiral Doenitz: “Lemp did his duty and died as a hero.” However, after the publication of Roskill’s book “The Secret Capture” in 1959, the hero became, in the eyes of German veterans, a scoundrel who had tarnished his honor: “He did not carry out the order to destroy secret materials! Hundreds of our boats were sunk, thousands of submariners died in vain,” “if he had not died at the hands of the British, we should have shot him.”

And in February 1942, the 4-rotor M4 replaced the 3-rotor M3 on boats. Bletchley Park has hit a wall again. All that remained was to hope for the capture of a new vehicle, which happened on October 30, 1942. On this day, Captain-Lieutenant Heidtmann's U-559 northeast of Port Said was heavily damaged by British depth charges. Seeing that the boat was sinking, the crew jumped overboard without destroying the encryption equipment. She was found by sailors from the destroyer Petard. As soon as they handed over the loot to the boarding party that arrived in time, the mangled boat suddenly capsized, and two daredevils (Colin Grazier, Antony Fasson) went with it to a kilometer depth.

The spoils were the M4 and the "Brief Call Sign Log"/"Brief Weather Code" brochures, printed with soluble ink on pink blotting paper, which the radio operator was supposed to throw into the water at the first sign of danger. It was with their help that the codes were opened on December 13, 1942, which immediately gave the headquarters accurate data on the positions of 12 German boats. After a 9-month break (black-out), the reading of ciphergrams began again, which did not stop until the end of the war. From now on, the destruction of the “wolf packs” in the Atlantic was only a matter of time.

Immediately after rising from the water, German submariners were completely undressed and all their clothes were taken away in order to search for documents of interest to intelligence (for example, code tables of the Enigma cipher machine).

A whole technology for such operations has been developed. Bombs were used to force the boat to the surface and they began shelling with machine guns so that the Germans, remaining on board, would not begin to sink. Meanwhile, a boarding party was approaching her, aiming to look for “something like a typewriter next to the radio station,” “disks with a diameter of 6 inches,” any magazines, books, papers. It was necessary to act quickly, and this was not always possible. Often people died without obtaining anything new.

In total, the British captured 170 Enigmas, including 3-4 naval M4s. This made it possible to speed up the decryption process. When 60 “bombs” were turned on simultaneously (i.e., 60 sets of 108 reels), the search for a solution was reduced from 6 hours to 6 minutes. This already made it possible to quickly respond to uncovered information. At the peak of the war, 211 “bombs” operated around the clock, reading up to 3 thousand German encryption messages daily. They were served in shifts by 1,675 female operators and 265 mechanics.

When Station X could no longer cope with the huge flow of radio interceptions, some of the work was moved to the United States. By the spring of 1944, 96 “Turing bombs” were working there, and a whole decryption factory had arisen. In the American model, with its 2000 rpm, the decoding was 15 times faster. Confrontation with the M4 has become a chore. Actually, this was the end of the fight with Enigma.

Consequences

Hacking the Enigma codes provided the Anglo-Saxons with access to almost all the secret information of the Third Reich (all armed forces, SS, SD, Foreign Ministry, post office, transport, economy), gave great strategic advantages, and helped them win victories with little bloodshed.

"Battle of Britain" (1940): Having difficulty repelling the German air pressure, in April the British began reading Luftwaffe radiograms. This helped them to properly operate their last reserves, and they won the battle. Without breaking Enigma, a German invasion of England would have been very likely.

“Battle of the Atlantic” (1939-1945): not taking the enemy from the air, Hitler strangled him with a blockade. In 1942, 1,006 ships with a displacement of 5.5 million gross tons were sunk. It seemed that just a little more and Britain would fall to its knees. But the British, reading the coded communications of the “wolves,” began to mercilessly drown them and won the battle.

Operation Overlord (1945): before the landing in Normandy, the Allies knew from the transcript about ALL German countermeasures to repel the landing, every day they received accurate data on positions and defense forces.

The Germans constantly improved Enigma. Operators were trained to destroy it in case of danger. During the war, the keys were changed every 8 hours. Cipher documents dissolved in water. The creators of the “Riddle” were also right: it is in principle impossible to decipher its messages manually. What if the enemy opposes this machine with his own? But that’s what he did; Capturing new copies of technology, he improved his “anti-Enigma”.

The Germans themselves made his work easier. So, they had an “indicator procedure”: at the beginning of the ciphergram, the setting was sent twice (rotor number / their starting positions), where a natural similarity was visible between the 1st and 4th, 2nd and 5th, 3rd and 6 characters. The Poles noticed this back in 1932 and cracked the code. A significant security hole was the weather reports. Submariners received them from the base “reliably” encrypted. On land, the same data was encrypted in the usual way - and now in the hands of crackers there is already a set of known combinations, and it is already clear which rotors work, how the key is built. Deciphering was facilitated by the standard language of messages, where expressions and words were often repeated. So, every day at 6:00 the weather service gave an encrypted forecast. The word "weather" was required, and clumsy German grammar placed it in its exact place in the sentence. Also: the Germans often used the words “Vaterland” and “Reich”. The British had employees with their native German language (native speakers). Putting themselves in the place of the enemy coder, they searched through a lot of encryption for the presence of these words - and brought the victory over Enigma closer. It also helped that at the beginning of the session the radio operator always indicated the call sign of the boat. Knowing all their call signs, the British determined the rotor scheme, obtaining approximate cipher combinations of some characters. “Forced information” was used. So, the British bombed the port of Calais, and the Germans gave an encryption, and in it - already known words! Decryption was made easier by the laziness of some radio operators, who did not change the settings for 2-3 days.

The Nazis were let down by their penchant for complex technical solutions where simpler methods were more reliable. They didn't even know about the Ultra program. Fixated with the idea of Aryan superiority, they considered Enigma impenetrable, and the enemy’s awareness was the result of espionage and betrayal. They managed to get into the London-Washington government communications network and read all the interceptions. Having revealed the codes of sea convoys, they directed “wolf packs” of submarines at them, which cost the Anglo-Saxons 30,000 lives of sailors. However, with an exemplary order in the organization of affairs, they did not have a single decryption service. This was done by 6 departments, which not only did not work together, but also hid their skills from their fellow competitors. The communication system was assessed for resistance to hacking not by cryptographers, but by technicians. Yes, there were investigations into suspicions of a leak via the Enigma line, but the specialists could not open the authorities’ eyes to the problem. “The chief submariner of the Reich, Admiral Doenitz, did not understand that it was not radars, not direction finding, but the reading of ciphergrams that made it possible to find and destroy their boats” (post-war report of the Army Security Agency/USA).

It is said that without breaking the Nazis' main encryption machine, the war would have lasted two years longer, would have cost more casualties, and might not have ended without the atomic bombing of Germany. But this is an exaggeration. Of course, it’s more enjoyable to play by looking at your opponent’s cards, and decoding is very important. However, she did not defeat the Nazis. After all, from February to December 1942, without having a single decipherment, the Allies destroyed 82 German submarines. And on land, the Germans in a huge number of operations sent information by wire, by courier, by dogs or pigeons. During World War II, half of all information and orders were transmitted in this way.

...In the summer of 1945, the guys from TICOM (Target Intelligence Committee, an Anglo-American office for the seizure of German information technologies) confiscated and took away the latest Enigmas and specialists in them. But the car (Schlüsselkasten 43) continued to be produced: in October - 1000, in January 1946 - already 10,000 units! Its hacking remained a secret, and the myth about the absolute reliability of the product of “German genius” spread throughout the planet. The Anglo-Saxons sold thousands of Enigmas to dozens of countries of the British Commonwealth of Nations on all continents. There they worked until 1975, and the “benefactors” read the secrets of any government.

Enigma was used by many: the Spanish - commercial, the Italian Navy - Navy Cipher D, the Swiss - Enigma K. The Japanese clone of Enigma was the 4-rotor GREEN. The British made their Typex according to drawings and even from Enigma parts, piratedly using the patent.

Today there are up to 400 working copies of Enigma in the world, and anyone can purchase it for 18-30 thousand euros.

The chatterbox will be shot!

The measures taken to conceal the Ultra program were unprecedented. German ships and submarines were sunk after gutting so that the enemy would not realize they had been captured. The prisoners were isolated for years, their letters home were intercepted. Their chatterbox sailors were exiled to serve in darkness like the Falkland Islands. The received intelligence data underwent revision/distortion, and only then was transferred to the troops. The full mastery of the “Riddle” was hidden throughout the war even from “big brother” the USA. Knowing from the encryption about the upcoming bombing of Coventry on November 14, 1940, the population of the city was not evacuated so that the Germans would not realize that they were being “read”. This cost the lives of half a thousand townspeople.

At the height of the war, up to 12 thousand people worked in the Ultra program: mathematicians, engineers, linguists, translators, military experts, chess players, puzzle specialists, operators. Two thirds of the staff were wrens (Women's Royal Naval Service). While doing their tiny part of the job, no one knew what they were doing as a whole, and the word "Enigma" had never been heard. People who did not know what was happening behind the next door were constantly reminded: “For chatting about work, you will be shot.” Only 30 years later, after the secrecy was lifted, some of them dared to admit what they did during the war. A. Turing wrote a book about breaking Enigma: the British government did not allow its release until 1996!

The Nazis did not have their own “mole” in Bletchley Park. But for the USSR what was happening there was no secret. Moscow received small doses of “ultra” category information on the direct orders of Churchill, despite the protests of his headquarters. In addition, British intelligence officer John Cairncross, who had access to secret data, supplied the Russians with them without restriction, including Enigma decryptions.

The success of the Enigma crackers was based on just a few brilliant ideas expressed at the right time. Without them, Enigma would have remained a Mystery. Stuart Milner-Berry, British chess champion, one of the main burglars at Bletchley Park: “There is no such example since ancient times: the war was fought in such a way that one enemy could constantly read the most important messages from the army and navy of the other.”

After the war, the Turing bombs were destroyed for safety reasons. 60 years later, the Enigma & Friends society tried to recreate one of them. Only the collection of components took 2 years, and the assembly of the machine itself took 10 years.

The Bombe machine, developed by British mathematician Alan Turing, was of great importance during the Second World War. Turing's invention helped crack German messages encoded by the legendary Enigma machine.

The Turing machine significantly increased the speed of decoding intercepted German messages. This allowed Allied forces to respond to classified intelligence within hours rather than weeks.

Much has been said about Turing's genius, his troubled personal life and his tragically early death. Hollywood even made a film about him. But how much do you know about the machine he built, the principle of hacking the machine, and the impact it had on the course of the war?

We share unknown facts about Turing's invention.

1. Turing didn’t come up with his machine himself.

In fact, Turing's ingenious invention, the Bombe machine, is a continuation of the work of Polish mathematicians Marian Rejewski, Henryk Zygalski and Jerzy Rozycki.

Poland's Bombe succeeded thanks to a flaw in German encryption that double-encrypted the first three letters at the beginning of each message, allowing codebreakers to look for patterns.

Exactly how the Bombe machine worked remains a mystery, but by using six of these machines in parallel, the all-important Enigma Ringstellung (the order of the coding ring) could be discovered in just in a couple of hours.

2. The Germans perfected Enigma

At some point, German cryptographers discovered and fixed the weakness of double encryption. Then the British needed a more advanced solution, and Turing and his team got involved in the work.

Using information provided by the Poles, Turing began hacking Enigma messages using his own "computer".

His methods were based on the assumption that every message contained a cheat sheet - a known piece of German plaintext at a familiar location in the message.

In one example it was weather forecast in Atlantic, which was recorded in the same format every day. Location detection equipment at listening stations allowed codebreakers to determine where a message was coming from, and if it matched the location of a weather station, it was likely that the word "wettervorhersage" (weather forecast) would be present in every message.

Another curious clue for Turing was Enigma's inability to encode a letter as itself. That is, S could never have been S.

3. Enigma has become almost perfect

Even taking into account all the disadvantages of Enigma, it was difficult to crack the code almost impossible. There was not enough time or manpower to work out all possible combinations. This is due to the fact that each letter, when entered into the Enigma machine, was encrypted differently each time.

So, even if you guessed one keyword that offered hints, it took reduce the odds 158,962,555,217,826,360,000 to 1– the exact number of ways to configure Enigma machines.

Moreover, every day a new code had to be cracked to account for the Germans changing the settings at midnight.

4. Turing's team did the opposite

Instead of guessing the key, Bombe used logic to reject certain possibilities. As Arthur Conan Doyle said, “When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how incredible, must be true.”

This method, although successful, still provided a range of possible correct answers for the German ring settings. So more work needed to be done to narrow it down to the right one.

Using testing machine process repeated until the correct answer was found.

This gave the crackers part of the key, but not all of it. Then you had to use what you learned and figure out the rest of the key.

Once the code was cracked, Turing's team would set up an Enigma machine with the correct key of the day and decipher every message intercepted that day.

5. Turing machine today costs 320 million rubles

The "bombs" were 7 feet wide, 6 feet 6 inches tall and literally weighed a ton. They had 12 miles of wires(!) and 97,000 different parts.

The decoder prototype was built at a cost of £100,000, equivalent to around £4 million today. Almost 320 million rubles at the current exchange rate!

In essence, the Turing bomb was an electromechanical machine consisting of 36 different Enigma machines, each containing the exact internal wiring of the German equivalent.

When "Bomb" is turned on, each of the riddles is allocated a pair of letters from the resulting cheat sheet text (for example, when D becomes T in a guessed word).

Each of the three rotors moves at a speed simulating the Enigma itself, testing approximately 17,500 possible positions until a match is found.

6. Turing's genius influenced the outcome of the war

After the Enigma machine was broken, 211 Bombe machines were built and operated around the clock. They were placed in various locations throughout Britain in case of possible explosions that could destroy these very complex and expensive samples.

Due to a shortage of captured Enigma machines, British Typex cipher machines were converted to working Enigma machines.

The fully decrypted messages were translated from German into English and then passed on to British intelligence.

At its peak, the Bombe machine could hack up to 3000 German messages per day. By the end of the war, she had handled 2.5 million messages, many of which gave the Allies vital information about German positions and strategy.

It is assumed that this knowledge played an important role in key battles.

According to many experts, Turing's invention shortened the war by two years.

Bank of England to issue £50 note in Turing's honor

Alan could have been born in India: his father Julius worked in the Indian Civil Service, and the family were just living in India when Ethel Sarah became pregnant. But the couple decided that it was better for the child to be born in London. Alan did just that.

From birth, Alan was, as they say, a strange child and at the same time a genius. According to some versions, he learned to read in just three weeks, and at the age of seven, Alan wanted to collect honey from wild bees during a picnic. To do this, he calculated the flight paths of insects among the heather and thus found the hive.

At the age of six, Alan Turing went to school, and at 13 he became a student at the famous private school Sherborne. It is curious that in Sherborne the humanities were much more valued, but Alan’s passion for mathematics was not encouraged. The school principal wrote to parents:

“I hope he won’t try to sit on two chairs at once. If he intends to remain in a private school, then he must strive to obtain an “education.” If he is going to be exclusively a “scientific specialist,” then a private school is a waste of time for him.”

There, in Sherborne, Alan met someone who became his close friend and, perhaps, his first love, Christopher Marcom. Unfortunately, the young man died from complications from bovine tuberculosis, leaving Alan in despair. It was this death that forced Turing to abandon his religious views and made him an atheist.

“I am sure that I will never meet again a companion so gifted and at the same time so charming,” Alan wrote to Marcom’s mother. “I shared with him my interest in astronomy (which he introduced me to), and he did the same for me... I know that I have to put as much energy, if not as much interest, into my work as I would have if I had he’s alive, that’s what he would like.”

Correspondence with his friend's mother continued for many years after Morcom's death, and all the letters were filled with tender memories of Christopher.

Alan entered King's College Cambridge, where his talents were already taken seriously. There he came up with the idea of a universal machine - it was still an abstract idea, from which the concept of a computer was later born. Alan studied mathematics and cryptography.

Bletchley Park, The Dilly Girls and The Turing Bomb

Bletchley Park was also called “Station X” or simply “BP” - it was a large mansion in the center of England, which during the Second World War was used for the needs of the main cryptographic department of Britain. Asa Briggs, a wartime historian and codebreaker, said: “Exceptional talent was needed at Bletchley, genius was needed. Turing was that genius."

Like any genius, he was strange. Colleagues called him by the short nickname Prof.

Historian Ronald Levin writes that Jack Goode, a cryptanalyst who worked with Turing, spoke of Alan as follows:

“In the first week of June every year he would have a bad attack of hay fever and would ride his bike to work wearing a gas mask to protect himself from the pollen. His bicycle was broken; the chain was falling off at regular intervals. Instead of fixing it, he counted the number of pedal revolutions through which the chain came off, got off the bike and manually adjusted it. Another time, he chained his mug to the radiator pipes to prevent it from being stolen.”

Because British men were at war, most of Bletchley's workers were women. Cryptographers worked long hours decoding intercepted messages.

“In 1939, the job of a codebreaker, although it required skill, was boring and monotonous,” says Andrew Hodges in The Universe of Alan Turing. “However, encryption was an integral attribute of radio communications. The latter was used in war in the air, at sea and on land, and a radio message for one became available to everyone, so the messages had to be rendered unrecognizable. They weren’t just made “secret,” like those of spies or smugglers, but the entire communication system was classified. This meant errors, limitations, and hours of work on each message. However, there was no choice."

One of the most famous teams was a group of women called the Dilly Girls. They worked under the direction of cryptanalyst Dilwin Knox. It was these women who deciphered the famous Enigma code, and Turing worked on the creation of a cryptanalytic machine. One of the "Dilly girls" was Joan Clarke.

Joan Clark

Turing became incredibly close to Joan, a rather reserved girl. She worked on deciphering maritime codes in real time, one of the most stressful jobs at Bletchley.

“We spent time together,” she recalled in a 1992 interview with BBC Horizon. “We went to the movies, but it was a big surprise for me when he said: “Will you agree to marry me?” I was surprised, but I didn’t doubt it for a second, I answered “yes,” and he knelt in front of my chair and kissed me even though we had no physical contact. The next day we went for a walk after lunch. And then he said that he had homosexual tendencies. Naturally, this worried me a little - I knew for sure that this would be forever.”

Turing broke off the engagement a few months later, but despite this they remained close friends.

Graham Moore, screenwriter of The Imitation Game, believes it was their strangeness that brought Alan and Joan together: “They were both outcasts and that was something they had in common, they saw things differently.”

Gross obscenity

In December 1951, 39-year-old Turing met Arnold Murray. He was 19. An unemployed handsome young man, thin, with big blue eyes and blond hair. Alan invited Arnold to a restaurant. After some time they saw each other again and spent the night together.

Although Alan tried to offer Arnold money, he said he didn't want to be treated like a prostitute. He "borrowed" money from Turing several times, and some time later someone robbed Alan's house.

Arnold confessed to his lover that his friend did it. Alan reported the robbery to the police, but he was forced to admit his homosexuality.

Alan was confident that parliament would soon legalize homosexual relations.

Arnold and Alan appeared in court. They were charged with “gross indecency” and both were found guilty. Arnold received parole, and Alan was given a choice: prison time or treatment for homosexuality with hormones.

Turing wrote to his friend Philip Hall: “I am given a suspended sentence for a year and am required to undergo treatment for the same period. The drugs are supposed to reduce sexual desire while it lasts... Psychiatrists seem to have decided that there is no use in getting involved with psychotherapy.”

And he also said: “Without a doubt, another person will come out of all this, but I don’t know who exactly.”

Poisoned Apple

On June 8, 1954, Turing's housekeeper found him dead in his room. Next to him lay a bitten apple, which most likely became the cause of death. Alan was very fond of Disney's Snow White. According to biographers Hodges and David Leavitt, he took "particularly acute pleasure in the scene where the Evil Queen plunges her apple into the poisonous drink."

Most likely, Alan poisoned the apple with cyanide and ate it.

In August 2009, British computer programmer John Graham-Cumming wrote a petition calling on the British government to apologize for persecuting Turing for his homosexuality. It collected more than 30,000 signatures, and Prime Minister Gordon Brown issued a statement of apology:

“Thousands of people have demanded justice for Alan Turing and demanded that he be treated appallingly. Turing was treated according to the law of that time, and we cannot turn back time, what they did to him was, of course, unfair. I and all of us deeply regret what happened to him. On behalf of the British Government and all those who live freely thanks to Alan's work, I say: Forgive us, you deserve better.

Photo: Getty Images, REX