Knowing another language not only allows you to communicate with foreigners, travel and earn more money, but also expands the capabilities of the brain, delays senile dementia and increases the ability to concentrate. Read on and you will understand why.

Famous polyglots

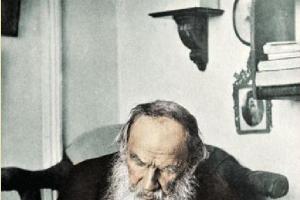

It is known that Leo Tolstoy spoke and read fluently in French, English and German, read in Czech, Italian and Polish, and had a reasonable command of Ukrainian, Greek, Church Slavonic and Latin. In addition, the writer was engaged studying Turkish, Dutch, Hebrew and Bulgarian languages.

We assume that he did this not at all in order to boast of his abilities or to be able to talk with a foreigner, but to develop his mental abilities, and simply because he could not remain idle, live at least a day without mental labor. Until his old age, Tolstoy worked, joyfully communicated with every person and thought deeply about many phenomena.

Other famous polyglots: Empress Catherine II (5 languages), statesman commander Bogdan Khmelnitsky (5 languages), inventor Nikola Tesla (8 languages), writer Alexander Griboyedov (9 languages), Pope John Paul II (10 languages) and writer Anthony Burgess (12 languages).

It should be noted that there are a lot of polyglots among scientists, and especially linguists. The capabilities of the human brain are demonstrated by people who know several dozen languages and dialects. Thus, our contemporary Willy Melnikov, a researcher at the Russian Institute of Virology, knows more than 100 languages, and professor at the University of Copenhagen, linguist Rasmus Konstantin Rask spoke 230 languages (and knew their grammar and linguistics perfectly).

English as a brain trainer

In 2013, an experiment was conducted at the University of Edinburgh (Scotland) to test the ability to concentrate among 38 monolingual and 60 bilingual people under the age of 19. It is unclear whether young people learned a language because they could concentrate or acquired this ability because of the language, but the fact is that people who know two languages performed better, regardless of when they started learning or in high school.

If we theoretically accept language learning for the cause, and the ability to concentrate for the effect, this can be explained this way: when the brain needs to adapt to a second language, it must concentrate on the most important and discard the unnecessary. This helps you quickly translate the necessary phrases in your mind and more accurately understand your interlocutor, without being distracted by unfamiliar words, but perceiving the entire phrase as a whole.

But the ability to concentrate is not the only “bonus” for a polyglot. Scientists have concluded that tension in certain lobes of the brain at any age contributes to the formation of new neural connections and their adaptation to existing chains. Moreover, this happens both in childhood and in young or adulthood.

The above is confirmed by an experiment conducted at a translator academy in Sweden. Newly admitted students were offered learning foreign languages high complexity (Russian, Arabic or Dari language). The language had to be studied every day for many hours. At the same time, scientists monitored medical university students who were studying just as hard. At the beginning and end of the experiment (after 3 months), participants in both groups underwent MRI of the brain. It turned out that among students who studied medicine, the brain structure did not change, but among those who intensively mastered language, the part of the brain responsible for the acquisition of new knowledge (the hippocampus), long-term memory and spatial orientation increased in size.

Finally, or anyone else language has a positive effect on the preservation of mental abilities in old age. This was confirmed by the results of a study that lasted from 1947 to 2010. 853 study participants took an intelligence test at the beginning and end of the experiment, 63 years later. People who knew two or more languages showed higher mental and psychological abilities than their peers who spoke only their native language all their lives. Overall, their brain health was better than what is considered normal at that age.

Important conclusions can be drawn from these studies:

- Our brain needs exercise just like our muscles and ligaments. If we want to maintain good mental abilities into old age, we need to constantly occupy our mind with something. And one of the most effective means is foreign languages.

- A well-functioning brain almost always means a fuller, happier life, and most certainly success in life. Therefore, if we need to achieve wealth, self-realization and the respect of people, it is necessary to study languages or, if we already know how to read a foreign language, start in-depth study of English and learn to communicate freely with its carriers.

- It doesn’t matter at all when we start learning a foreign language: at any age, the brain is rebuilt, new neural connections are formed in it, as well as an increase in its individual parts, which leads to a more complete perception of reality, increased mental abilities, including memorization and concentration.

If you are learning English, then, of course, you have heard about polyglots who managed to learn 5/10/30/50 languages. Which of us doesn’t have the thought: “Surely they have some secrets, because I’ve been learning one and only English for years!” In this article we will present the most common myths about those who successfully learn foreign languages, and also tell you how polyglots learn languages.

A polyglot is a person who can communicate in several languages. Some of the most famous polyglots in the world are:

- Cardinal Giuseppe Mezzofanti, according to various sources, spoke 80-90 languages.

- Translator Kato Lomb spoke 16 languages.

- Archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann spoke 15 languages.

- Writer Leo Tolstoy spoke 15 languages.

- Writer Alexander Griboyedov spoke 9 languages.

- Inventor Nikola Tesla spoke 8 languages.

- Writer Anthony Burgess spoke 12 languages.

- Luca Lampariello

- Sam Jandreau

- Ollie Richards is a contemporary and speaks 8 languages.

- Randy Hunt is a contemporary and speaks 6 languages.

- Donovan Nagel is a contemporary and speaks 10 languages.

- Benny Lewis is a contemporary and speaks 11 languages.

It should be said that basically all polyglots know 2-3 languages at a high level, and speak the rest at the “survival” level, that is, they can communicate on simple topics.

Another interesting feature is that the first foreign language is always the hardest and takes the longest to learn, while subsequent ones are learned much faster and are easier. It is especially easy to learn languages of one group, for example: Italian, French and Spanish.

7 common myths about polyglots

Myth #1: Polyglots are people with special abilities for languages.

Some people believe that polyglots do not need to strain at all: the languages themselves are absorbed in their heads without effort or practice. There is an opinion that those who know many languages have a different brain structure, they easily perceive and reproduce information, grammar is given to them without studying, on its own, etc.

Is it true:

A polyglot is an ordinary person who likes to learn several languages and who makes every effort to do so. There is no such person who could not become a polyglot, because this does not require any special knowledge or mindset. All you need is work and passion.

Don’t be in a hurry to be fluent (you’ll frustrate yourself). Just enjoy the process. It’s slow and not always easy, but it can be enjoyable if you take the pressure off yourself.

Don't rush to fluency straight away (you'll only end up frustrated). Just enjoy the process. It will be slow and not always easy, but it can be fun if you don't push yourself.

Myth #2: Polyglots have unique memories

There is an opinion that all polyglots have a phenomenal memory, so any languages are easy for them. People believe that polyglots remember the meanings of absolutely all unfamiliar words and grammatical structures from the very first time, so subsequently they can easily speak the language they are learning.

Is it true:

Polyglots do have a good memory, but many people confuse cause and effect: it is the study of languages that develops memory, and not unique innate abilities that make it possible to learn a language. Indeed, there are people who can boast of a unique memory, but this does not make them polyglots. The fact is that simply memorizing words or phrases is not enough to fully learn a language.

Myth #3: Polyglots started learning languages at a young age

Another popular myth goes something like this: “Polyglots are people whose parents took them to language courses since childhood. Children find it easier to study, so today these people easily speak several foreign languages.”

Is it true:

For the most part, polyglots are people who are in love with foreign languages. And this love came already at a conscious age. Those who learned foreign languages as children do not have any advantages over adult learners. Most linguists and psychologists are convinced that languages are even easier for adults, because an adult, unlike a child, consciously takes this step and understands why he needs to read texts or translate sentences. Read the article “”, you will see that adults have their own advantages over children in learning foreign languages.

Myth #4: Polyglots can learn any language in 3-5 months

The issue of the need to study English and other languages is especially relevant today, so almost every day we read another article or watch an interview with a polyglot. These people sometimes claim that they learned a foreign language in 3-5 months. At the same time, many polyglots, in their interviews or articles, immediately offer you to purchase for money a language learning course that they themselves invented. Is it worth spending money on this?

Is it true:

In fact, polyglots rarely clarify what they mean by the phrase “I learned a language in 5 months.” As a rule, during this time a person has time to learn the basics of grammar and basic vocabulary in order to explain himself in everyday communication. But to talk about more complex topics, for example about life and the structure of the Universe, any person needs more than 5 months. Those who speak several languages really well will tell you that they have been studying them for years and are constantly improving their knowledge. Therefore, if you plan to advance beyond the “read, translate with a dictionary” level, prepare not for 3-5 months, but for at least 1-2 years of studying your first foreign language “from scratch”.

Myth #5: Polyglots have a lot of free time

When we read articles about polyglots, it seems that all they do is give interviews from morning to night and tell how they managed to achieve success in the field of learning foreign languages. This is where the myth arose that those who don’t work learn languages; they say they mastered English simply “out of nothing to do.”

Is it true:

To confirm our words, watch this video by polyglot Ollie Richards, he talks about life hacks that will help even the busiest people learn a language:

Myth #6: Polyglots travel a lot

Many people believe that you can “truly” learn a foreign language only abroad, in the country of native speakers of that language. There is an opinion that abroad you can completely “immerse” yourself in the subject you are studying, create an ideal language environment, etc. It turns out that in order to become a polyglot, you need to constantly travel around countries.

Is it true:

In fact, most polyglots say that they communicate a lot with native speakers of the language they are learning, are interested in their way of life, culture, etc. However, this does not mean that people studying foreign languages travel 365 days a year. Technologies allow every person to communicate with people from any country without leaving home. Visit the language exchange sites listed in this article. On them you can find someone to talk to from the USA, Great Britain, Australia, and any other country. Polyglots take advantage of this same opportunity and successfully learn new languages. In the article "" we provided 15 tips for creating a language environment for learning English in your native country.

You can recreate an immersion environment at home, by streaming movies, listening to podcasts, playing music, and reading in your target language... all you need is an internet connection.

You can immerse yourself in a language environment at home by watching movies, listening to podcasts and music, reading in your target language... all you need is an internet connection.

Myth #7: Polyglots have a lot of money

This myth is closely related to the previous two: people believe that polyglots do not work, but only travel. In addition, people think that polyglots constantly spend large sums on educational materials: they buy tutorials and dictionaries, take expensive lessons from native-speaking teachers, and travel abroad for language courses. People believe that polyglots have a lot of money and therefore opportunities to learn foreign languages.

Is it true:

At the time of writing this article, “millionaire” and “polyglot” are not identical concepts. As we have already found out, polyglots are not on a continuous journey and among them there are many who are just like you and me, ordinary working people. It’s just that those who want to know many languages use every opportunity to gain knowledge. It should be said that we have a lot of such opportunities: from all kinds of courses to thousands of educational Internet resources. For example, you can learn English on the Internet completely free of charge, and to make it easier for you to find the sites you need, we constantly write articles with collections of tips and useful resources for developing certain skills. Subscribe to our newsletter and you won't miss important information.

Secrets of polyglots: how to learn foreign languages

1. Set yourself a clear goal

Learning a foreign language "because everyone else is learning it" won't last long, so decide why you need to know it. The goal can be anything: from serious, for example, to get a position in a prestigious company, to entertaining, like “I want to understand what Sting sings about.” The main thing is that your goal motivates you and in every possible way strengthens your desire to learn English. To strengthen your desire to learn a language, we advise you to read our articles “” and “”.

2. At the beginning of your studies, take at least a few lessons from a teacher

We've all read about how polyglots master any language on their own. However, many polyglots write blogs and often indicate that they started learning the language with a teacher, and after learning the basics they moved on to independent learning. We recommend doing the same: the teacher will help you lay a solid foundation of knowledge, and you can build subsequent “floors” yourself if you wish. If you decide to follow this advice, we suggest you try it with one of our experienced teachers. We can help you “promote” English to any level of knowledge.

3. Speak out loud from the first day of learning a new language

Even if you are learning your first ten words, say them out loud, this way you will remember the vocabulary better. In addition, you will gradually develop correct pronunciation. From the very first day, look for interlocutors to communicate with. For beginners, the ideal “partner” for developing oral speech would be a professional teacher, and at a higher level, you can look for an interlocutor on language exchange sites and hone your speaking skills with a native speaker. Please note: almost all polyglots claim that the most effective and interesting method of learning a new language is communicating with native speakers. At the same time, polyglots say that during communication, words and grammatical structures are easier to remember: you do not force yourself to study them, but remember them during an interesting conversation.

My absolute favorite language learning activity is talking to people! And it turns out, that’s pretty convenient, because that’s the whole reason we learn languages anyway, right? We learn the language in order to use it. And since language is a skill, the best way to learn it is by using it.

My favorite activity in language learning is communicating with people! And it turns out that this is quite convenient, because this is the reason we learn languages, right? We learn a language in order to use it. And since language is a skill, the best way to improve it is to use it.

4. Learn phrases, not individual words.

Watch this video by Luca Lampariello, he talks about how to learn new words (you can turn on Russian or English subtitles in the settings).

5. Don't get bogged down in theoretical grammar.

But this advice must be understood correctly, because lately the opinion that English grammar is unnecessary knowledge has been actively discussed on the Internet. Allegedly, for communication it is enough to know three simple tenses and a lot of words. However, in the article “” we explained why this opinion is fundamentally wrong. What do polyglots mean? They encourage us to pay less attention to theory, and more to practical exercises, the use of grammatical structures in oral and written speech. Therefore, immediately after familiarizing yourself with the theory, proceed to practice: do translation exercises, grammar tests, use the studied structures in speech.

6. Get used to the sound of new speech

I love to listen to podcasts, interviews, audiobooks or even music in my target language while walking or driving. This makes efficient use of my time and I don’t feel like I’m making any particular kind of effort.

I love listening to podcasts, interviews, audio books, or even music in the language I'm learning while I'm walking or driving. This allows me to use my time effectively without feeling like I'm making any special effort.

7. Read texts in the target language

While reading texts, you see how the grammar you are studying “works” in speech and how new words “cooperate” with each other. At the same time, you use visual memory, which allows you to remember useful phrases. On the Internet you can find texts in any language for beginners, so you need to start reading from the very first days of learning the language. Some polyglots advise practicing, for example, reading text in parallel in Russian and English. This way you can see how sentences are constructed in the language you are learning. In addition, polyglots claim that this allows them to wean themselves from the harmful habit of translating speech word for word from their native language into the target language.

8. Improve your pronunciation

9. Make mistakes

“Get out of your comfort zone!” - this is what polyglots call us to. If you are afraid to speak the language you are learning or try to express yourself in simple phrases to avoid mistakes, then you are deliberately creating an obstacle for yourself to improve your knowledge. Don’t be shy about making mistakes in the language you’re learning, and if you’re so tormented by perfectionism, take a look at RuNet. Native speakers of the Russian language, without a shadow of embarrassment, write words like “potential” (potential), adykvatny (adequate), “pain and numbness” (more or less), etc. We urge you to take an example from their courage, but at the same time try to take into account your own mistakes and eradicate them. At the same time, polyglots remind us of how children learn to speak their native language: they begin to speak with mistakes, adults correct them, and over time the child begins to speak correctly. Do the same: it's okay to learn from your mistakes!

Make at least two hundred mistakes a day. I want to actually use this language, mistakes or not.

Make at least two hundred mistakes a day. I want to use this language, with or without errors.

10. Exercise regularly

The main secret of polyglots is diligent study. There is not a single person among them who would say: “I studied English once a week and learned the language in 5 months.” On the contrary, polyglots, as a rule, are in love with learning languages, so they devoted all their free time to it. We are sure that anyone can find 3-4 hours a week to study, and if you have the opportunity to study for 1 hour a day, any language will conquer you.

11. Develop your memory

The better your memory is, the easier it will be to remember new words and phrases. Learning a foreign language in itself is an excellent memory training, and to make this training more productive, use different ways of learning the language. For example, solving is a fun and useful activity for both learning and memory. - another good idea for training: you can learn the lyrics of your favorite hit by heart, this way you will remember several useful phrases.

12. Follow the example of successful people

Polyglots are always open to new ways of learning; they do not stand still, but are interested in the experiences of other people who successfully learn foreign languages. We have devoted several articles to some of the most famous polyglots; you can read about the experience of learning languages, or study.

13. Curb your appetite

The variety of materials allows you not to get bored and enjoy learning a foreign language, but at the same time, we advise you not to “spray yourself”, but to focus on some specific methods. For example, if on Monday you took one textbook, on Tuesday you grabbed a second one, on Wednesday you studied on one site, on Thursday on another, on Friday you watched a video lesson, and on Saturday you sat down to read a book, then by Sunday you risk getting “porridge” there is an abundance of material in your head, because their authors use different principles for presenting information. Therefore, as soon as you start learning a new language, determine the optimal set of textbooks, websites and video lessons. There shouldn’t be 10-20 of them; limit your “appetite”, otherwise scattered information will be poorly absorbed. You will find ideas for choosing materials that suit you in our article “”, where you can download a free list of the “best” materials for learning a language.

14. Enjoy learning

Among the famous polyglots there is not a single person who would say: “Learning languages is boring, I don’t like to do it, but I want to know many languages, so I have to force myself.” How do polyglots learn languages? These people enjoy not just the understanding that they know a foreign language, but also the learning process itself. Do you think studying is boring? Then use interesting language learning techniques. For example, or is unlikely to seem boring to anyone.

Languages are not something one should study, but rather live, breathe and enjoy.

Languages are not something to be learned, but rather something to be lived, breathed and enjoyed.

Now you know how polyglots learn languages. As you have seen, everyone can learn foreign languages, regardless of “giftedness” and the number of banknotes. There is nothing complicated in the advice of polyglots on learning languages; all techniques are accessible to anyone and are easily applied in practice. Try to follow these recommendations and enjoy learning.

On October 7, the outstanding linguist, semiotician, and anthropologist Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich Ivanov passed away

IN Yacheslav Vsevolodovich Ivanov is a truly legendary figure. He belonged to that rare type of scientists today who can confidently be called encyclopedists. Few can compare with him in the scope of cultures, in the variety of interdisciplinary connections identified in his semiotic and cultural studies. It is difficult to name a humanities science to which he did not make some contribution. He is the author of more than one and a half dozen books and more than 1,200 articles on linguistics, literary criticism and a number of related humanities, many of which have been translated into Western and Eastern languages.

Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich was born on August 21, 1929 in Moscow in the family of the writer Vsevolod Ivanov, a man with a wide range of interests, a connoisseur of poetry and oriental cultures, a bibliophile who paid great attention to the comprehensive education of his son. Already in our time, Vyacheslav Ivanov recalled: “I was lucky, simply because of my family, because of my parents and their friends, to be in the circle of many remarkable people since childhood,” who had a significant influence on the development of the young man. It is no coincidence that a significant part of his scientific research is devoted to people whom he knew since childhood.

He constantly turned to Russian literature of the 20th century, with which, so to speak, he was connected by family ties. He is occupied by the relationship between poetic manifestos and the artistic practice of representatives of the Russian literary avant-garde, parallels and connections between writers who remained in Russia and writers of the Russian diaspora. Ivanov is particularly interested in the biography of Maxim Gorky, whom he knew as a child and saw more than once. In his historical essays, Ivanov seeks to understand the history of relations between writers and authorities during the Soviet period. He was interested in unofficial literature of the Stalin era, the last years of Gorky's life and the circumstances of his death, and the relationship between Stalin and Eisenstein.

Cuneiform and semiotics

In 1946, after graduating from school, Ivanov entered the Romance-Germanic department of the Faculty of Philology of Moscow State University, from which he graduated in 1951.

And already in 1955, Ivanov defended his thesis on the topic “Indo-European roots in the cuneiform Hittite language and the features of their structure,” which made such an impression on the academic council of Moscow State University that he considered the dissertation worthy of a doctorate - this happens in mathematics, but is extremely rare happens in the humanities. However, the Higher Attestation Commission did not approve the doctoral degree under a far-fetched pretext. And the new defense was hampered due to Ivanov’s participation in human rights activities. Only in 1978 did he manage to defend his doctorate at Vilnius University.

After completing his graduate studies, Ivanov was retained at the department at Moscow State University, where he taught ancient languages and taught courses in comparative historical linguistics and introduction to linguistics. But the scope of a traditional academic career was narrow for him. In 1956–1958, Ivanov, together with the linguist Kuznetsov and the mathematician Uspensky, led a seminar on the application of mathematical methods in linguistics. In fact, he stood at the origins of a new discipline that arose in those years - mathematical linguistics, to which he later devoted many of his works.

And then he showed his stormy social temperament, expressing disagreement with

Ivanov, together with the linguist Kuznetsov and the mathematician Uspensky, led a seminar on the application of mathematical methods in linguistics. In fact, he stood at the origins of a new discipline that arose in those years - mathematical linguistics

By attacking Boris Pasternak’s novel “Doctor Zhivago” and supporting the scientific views of Roman Yakobson. And for this in 1959 he was fired from Moscow State University. This decision was officially canceled by the university leadership only in 1989.

So that today’s reader can appreciate the courage of Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich’s behavior, we note that in those years he, apparently, was almost the only one who allowed himself to openly express his disagreement with the defamation of Pasternak.

But the dismissal, in a certain sense, played a positive role both in the fate of Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich and in the fate of science. Ivanov headed the machine translation group at the Institute of Precision Mechanics and Computer Science of the USSR Academy of Sciences. And then he became the creator and first chairman of the linguistic section of the Scientific Council of the USSR Academy of Sciences on cybernetics, headed by academician Axel Ivanovich Berg. Ivanov’s participation in the preparation of the problem note “Issues of Soviet science. General Issues of Cybernetics" under the leadership of Berg played a big role in the history of Russian science. Based on the proposals contained in this note, the Presidium of the USSR Academy of Sciences adopted a resolution on May 6, 1960 “On the development of structural and mathematical methods of language research.” Thanks to this, numerous machine translation laboratories, sectors of structural linguistics and structural typology of languages in academic institutions, departments of mathematical, structural and applied linguistics in several universities in the country were created. Ivanov participated in the preparation of curricula and programs for the department of structural and applied linguistics of the Faculty of Philology of Moscow State University, and in 1961 he gave a plenary report on mathematical linguistics at the All-Union Mathematical Congress in Leningrad.

He played an extremely important role in the development of domestic and world semiotics.

The works of Vyacheslav Ivanov on the subject of semiotics laid the general ideological basis for semiotic research in the USSR and the world-famous Moscow-Tartu semiotic school

Symposium on the structural study of sign systems, organized by the Scientific Council of the USSR Academy of Sciences on Cybernetics. The preface to the abstracts of the symposium written by Ivanov actually became a manifesto of semiotics as a science. Many experts believe that the symposium, together with the subsequent surge in research, produced a “semiotic revolution” in the field of all humanities in our country.

Ivanov’s works on the subject of semiotics laid the general ideological foundation for semiotic research in the USSR and the world-famous Moscow-Tartu semiotic school.

Humanitarian precision

Ivanov was constantly interested in the connection between linguistics and other sciences, especially the natural ones. In the 1970s and 1980s, he took an active part in experiments conducted in collaboration with neurophysiologists on the localization of semantic operations in various parts of the brain. He saw his task as creating a unified picture of knowledge so that, as he said, “the humanities would not be such outcasts against the background of those flourishing sciences that use precise methods.” Therefore, it is no coincidence that he is interested in the personalities of major natural scientists, to whom he devotes separate essays: geologist Vladimir Vernadsky, radio engineer Axel Berg, astrophysicist Joseph Shklovsky, cyberneticist Mikhail Tsetlin.

It is no coincidence that Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich saw similarities between linguistics and mathematics, emphasizing the mathematical rigor of phonetic laws and the closeness of the laws of language functioning and natural science laws.

Ivanov's linguistic interests were extremely diverse. These are general problems of the genealogical classification of the world's languages and Indo-European studies, Slavic linguistics and the ancient languages of the extinct peoples of the Mediterranean in their relation to the North Caucasian languages, the languages of the aborigines of Siberia and the Far East, the Aleutian language, Bamileke and some other African languages. He said about himself: “I am not a polyglot at all, although I speak all European languages. I can read like a hundred. But it's not that difficult."

But he not only studied languages. His track record includes dozens of translations of poems, stories, journalistic articles and scientific works from various languages of the world.

He said about himself: “I am not a polyglot at all, although I speak all European languages. I can read like a hundred. But it's not that difficult." But Ivanov not only studied languages. His track record includes dozens of translations of poems, stories, journalistic articles and scientific works from various languages of the world.

Thanks to the works of Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich Ivanov in the mid-1950s, Indo-European studies was actually revived in our country, one of the outstanding achievements of which was the monograph “Indo-European Language and Indo-Europeans. Reconstruction and historical-typological analysis of proto-language and proto-culture”, created jointly with Tamaz Gamkrelidze. This book was awarded the Lenin Prize in 1988 and caused great resonance throughout the world.

For more than half a century, starting in 1954, Ivanov systematically sums up the current state of linguistic comparative studies in the form of an updated version of the genealogical classification of the world's languages. Since the 1970s, this scheme has included kinship at the Nostratic level, and since the 1980s, Dene-Caucasian kinship. And each time it turns out that we are closer and closer to proving the hypothesis about the monogenesis of human languages, that is, about their origin from a single source, since more and more new connections are being discovered between language families.

From 1989 until recently, Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich was the director of the Institute of World Culture of Moscow State University. Since 1992 - Professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Since 2003 - director of the Russian Anthropological School at the Russian State University for the Humanities. Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich - Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences, member of the American Academy of Sciences and Arts.

In recent years, Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich has had a hard time experiencing the problems of Russian science. In one of his last speeches, he said: “I have been surprised lately to read various kinds of attacks on our science and its current situation. Believe me, I have been reading every day for more than a year what is written on this topic on the Internet in serious messages and in the scientific press. And the main thing is still a discussion of the works of our scientists, who enjoy worldwide fame and recognition anywhere, but not in our country... But I am sure that it is not the lack of money that is given to science, although this, of course, takes place, some minor troubles like the wrong exam form, but a much more significant thing is happening: science, literature, art, culture in our country have ceased to be the main thing to be proud of. It seems to me that the task that my generation was partly trying to accomplish was that we wanted to achieve a change in this situation, and to some extent, maybe some of us achieved.”

On October 7, Vyacheslav Vsevolodovich passed away.