She left nothing out to be successful. She spoke about Russia in words that would never have occurred to a natural Russian: This is not a country, this is a universe! During her lifetime...

She left nothing out to be successful. She spoke about Russia in words that would never have occurred to a natural Russian: This is not a country, this is a universe! During her lifetime she was called the Great. Our heroine is Catherine the Great.

Nobody knows the secret of her birth. Catherine took her to the grave. Was the officially recognized father legal? There were rumors that she was the daughter of Frederick II. Her father was called Ivan Ivanovich Betskov, pointing to the portrait resemblance. In the city of Shchetin there is not even a record of her birth.

Princess Fike's mother was of very free morals, and daddy was already quite an old man. Having left her native small German town, Fike never wanted to return there. In this sense she was a cosmopolitan.

Her brother wished to visit Russia. Catherine refused with the words: There are enough Germans in Russia even without him. During the famine years in Europe, she sent food to her fellow countrymen instead of the money that relatives asked for. An extraordinary woman of the 18th century. Who is she?

How did a German princess end up on the Russian throne and be able to stay there for the rest of her life? She came to Russia as the bride of the heir to the Russian throne, Peter Fedorovich. The wedding took place. But the husband showed no interest in the newlywed. He liked the maids and ladies-in-waiting of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna more.

For several years, Catherine remained alone in the palace, where everyone had a mistress or lover. It is difficult to maintain cleanliness where it is not taken care of. Catherine chose the path of knowledge. She diligently studied the Russian language and Russian history.

Those around her loved her. She didn't love anyone. The young princess had a flexible, tenacious character. She could unmistakably discern character traits and attracted those whom she could use in the future. Her husband, Pert Fedorovich, continued to have fun.

It was a dynastic marriage. An heir was expected from him. But he was still not there. Empress Elizaveta Petrovna tried to solve the problem simply.

She sent a clever man who was able to awaken the heart of Ekaterina Alekseevna.

The novel turned out to be successful and soon a clever man, Sergei Saltykov, went abroad as an ambassador, and Catherine and Peter had a son, Pavel. No one bothered to ensure that Catherine fell in love with the baby. The empress simply took him into her half.

For many years the woman waited in the wings. Elizabeth died, Peter III ascended the throne. But the strange character of the new emperor, which manifested itself even when he was heir to the throne, offended the Russian nobles and clergy.

One can argue for a long time about Peter III, but he did not come to the Russian court. But Catherine remembered everything. Having converted to Orthodoxy, she often went to church and stayed with noble people. By this time she had lived in Russia for 18 years. Everyone forgot that she is not a natural Russian.

The Russian court is not used to tolerating insults. Catherine became empress. It was not always convenient for her to sit on the Russian throne. But there was an opportunity to become the queen of Poland by marrying Stanislav Poniatowski.

But Russia... She loved Russia with cold snows, with daring dancers, with smart men. But Russia did not always give it its due. Under Catherine, bridges collapsed, houses where she stayed overnight burned, horses carried her, and she often lost her wardrobe.

The one sentenced to the rope will not burn or drown. Fate protected her. And Catherine worked tirelessly for the good of the country that became her fatherland. She woke up at 5 am. The average person did not know that she worked all day. And the ruling cabinet began to work early, together with her.

Already at 6 am, Catherine received the ministers with a report. During her reign, the country's borders expanded significantly. Crimea, Kabarda, Ukrainian lands, White Rus', part of Poland were annexed. Georgia, exhausted by Turkish raids, asked to join Russia.

State revenues increased 4 times. 144 cities were built, Russian troops won 78 brilliant victories. Russia's population increased by 14 million people. She built ships and museums, opened educational institutions for peasants and nobility.

Russia's prestige in the international arena was so high that “not a single cannon in Europe will fire without our consent.” But she was a politician. Her appearance combined sinfulness and kindness, majestic beginnings and base deeds, vulgar statements and a subtle taste for art.

She knew how to sew and knitted caps for her dogs. She turned jewelry from simple materials on a lathe. She did engraving and played billiards skillfully. Not chasing fashion, she believed that the court should be the most brilliant in Europe.

She insisted that courtiers always wear jewelry. Her yard shone with diamonds. She wrote plays that were staged on the court stage. She published a magazine and began issuing paper money. Favorite food: a piece of beef and a pickled cucumber, washed down with currant juice.

The Empress realized that she was very attractive to men. Her disposition was affable and simple. The most important thing that this great woman knew how to do was the ability to surround herself with smart minions. She did not have an ounce of jealousy if she saw that a ship called Russia was sailing in the right direction.

Catherine's main associates and favorites were the brilliant Prince Potemkin and Count Orlov. She didn't stop them from stealing. Catherine was generally tolerant of such vice. Knowing that the favorites would do more for Russia if they did not think about money, she turned a blind eye to their art.

Very hot-tempered, she never made decisions in the heat of the moment. I waited for my feelings to calm down. She didn't allow any rudeness. She didn’t give orders to the servants, but asked them to do something for her. Not a fan of arrogant ceremonies, she forbade anyone to stand in front of her.

I didn't like gloomy people. At the entrance to the Hermitage there was an inscription: The mistress of these places does not tolerate coercion. Ekaterina, who wrote Russian poorly, spoke Russian better than natural Russians.

The Great Empress had two sons. Legitimate son Pavel Petrovich and illegitimate son Bobrinsky Alexey Grigorievich. Catherine the Great passed away at the age of 67, leaving behind a grieving fatherland and people.

Ekaterina Alekseevna Romanova (Catherine II the Great)

Sophia Augusta Frederica, Princess, Duchess of Anhalt-Zerb.

Years of life: 04/21/1729 - 11/6/1796

Russian Empress (1762 – 1796)

Daughter of Prince Christian August of Anhalt-Zerbst and Princess Johanna Elisabeth.

Catherine II - biography

Born April 21 (May 2), 1729 in Schettin. Her father, Prince Christian Augustus of Anhalt-Zerb, served the Prussian king, but his family was considered impoverished. Sophia Augusta's mother was the sister of King Adolf Frederick of Sweden. Other relatives of the mother of the future Empress Catherine ruled Prussia and England. Sofia Augusta, (family nickname - Fike) was the eldest daughter in the family. She was educated at home.

In 1739, 10-year-old Princess Fike was introduced to her future husband, heir to the Russian throne Karl Peter Ulrich, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, who was the nephew of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, Grand Duke Peter Fedorovich Romanov. The heir to the Russian throne made a negative impression on high Prussian society, showing himself to be ill-mannered and narcissistic.

In 1744, Fike arrived in St. Petersburg secretly, under the name of Countess Reinbeck, at the invitation of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna. The bride of the future emperor accepted the Orthodox faith and received the name Ekaterina Alekseevna.

Marriage of Catherine the Great

On August 21, 1745, the wedding of Ekaterina Alekseevna and Pyotr Fedorovich took place. A brilliant political marriage turned out to be unsuccessful in terms of relationships. He was more formal. Her husband Peter was interested in playing the violin, military maneuvers and mistresses. During this time, the spouses not only did not become close, but also became complete strangers to each other.  Ekaterina Alekseevna read works on history, jurisprudence, works of various educators, learned the Russian language well, traditions and customs of her new homeland. Surrounded by enemies, not loved by her husband or his relatives, Ekaterina Alekseevna gave birth to a son (the future Emperor Paul I) in 1754, constantly fearing that she might be expelled from Russia. “I had good teachers - a misfortune with solitude,” she would write later. Sincere interest and love for Russia did not go unnoticed and everyone began to respect the wife of the heir to the throne. At the same time, Catherine amazed everyone with her hard work; she could personally brew her own coffee, light the fireplace, and even do her laundry.

Ekaterina Alekseevna read works on history, jurisprudence, works of various educators, learned the Russian language well, traditions and customs of her new homeland. Surrounded by enemies, not loved by her husband or his relatives, Ekaterina Alekseevna gave birth to a son (the future Emperor Paul I) in 1754, constantly fearing that she might be expelled from Russia. “I had good teachers - a misfortune with solitude,” she would write later. Sincere interest and love for Russia did not go unnoticed and everyone began to respect the wife of the heir to the throne. At the same time, Catherine amazed everyone with her hard work; she could personally brew her own coffee, light the fireplace, and even do her laundry.

Novels of Catherine the Great

Unhappy in her family life, in the early 1750s Ekaterina Alekseevna began an affair with guards officer Sergei Saltykov.

His royal aunt did not like the behavior of Peter III while still in the status of Grand Duke; he actively expressed his Prussian sentiments against Russia. The courtiers notice that Elizabeth favors his son Pavel Petrovich and Catherine more.

The second half of the 1750s was marked for Catherine by an affair with the Polish envoy Stanislav Poniatowski (who later became King Stanislav Augustus).

In 1758, Catherine gave birth to a daughter, Anna, who died before she was even two years old.

In the early 1760s, a dizzying, famous romance arose with Prince Orlov, which lasted more than 10 years.

In 1761, Catherine's husband Peter III ascended the Russian throne, and relations between the spouses became hostile. Peter threatens to marry his mistress and send Catherine to a monastery. And Ekaterina Alekseevna decides to carry out a coup with the help of the guard, the Orlov brothers, K. Razumovsky and her other supporters on June 28, 1762. She is proclaimed empress and sworn allegiance to her. The spouse's attempts to find a compromise fail. As a result, he signs an act of abdication from the throne.

In 1761, Catherine's husband Peter III ascended the Russian throne, and relations between the spouses became hostile. Peter threatens to marry his mistress and send Catherine to a monastery. And Ekaterina Alekseevna decides to carry out a coup with the help of the guard, the Orlov brothers, K. Razumovsky and her other supporters on June 28, 1762. She is proclaimed empress and sworn allegiance to her. The spouse's attempts to find a compromise fail. As a result, he signs an act of abdication from the throne.

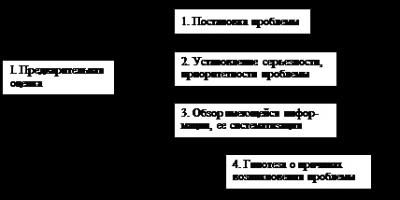

Reforms of Catherine the Great

On September 22, 1762, the coronation of Catherine II took place. And in the same year, the empress gave birth to a son, Alexei, whose father was Grigory Orlov. For obvious reasons, the boy was given the surname Bobrinsky.

The time of her reign was marked by many significant events: in 1762 she supported the idea of I.I. Betsky to create the first Orphanage in Russia. She reorganized the Senate (1763), secularized the lands (1763-64), abolished the hetmanate in Ukraine (1764) and founded the first women's educational institution in the capital at the Smolny Monastery. She headed the Statutory Commission 1767-1769. During her reign, the Peasants' War of 1773-1775 took place. (rebellion of E.I. Pugachev). Issued the Institution for governing the province in 1775, the Charter to the nobility in 1785 and the Charter to the cities in 1785.

Famous historians (M.M. Shcherbatov, I.N. Boltin), writers and poets (G.R. Derzhavin, N.M. Karamzin, D.I. Fonvizin), painters (D.G. Levitsky, F.S. Rokotov), sculptors (F.I. Shubin, E. Falcone). She founded the Academy of Arts, became the founder of the State Hermitage collection, and initiated the creation of the Academy of Russian Literature, of which she made her friend E.R. Dashkova the president.

Under Catherine II Alekseevna as a result of the Russian-Turkish wars of 1768-1774, 1787-1791. Russia finally gained a foothold in the Black Sea; the Northern Black Sea region, the Kuban region, and Crimea were also annexed. In 1783, she accepted Eastern Georgia under Russian citizenship. Partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were carried out (1772, 1793, 1795).

She corresponded with Voltaire and other figures of the French Enlightenment. She is the author of many fictional, journalistic, dramatic, and popular science works, and “Notes.”

External politics of Catherine 2 was aimed at strengthening Russia's prestige on the world stage. She achieved her goal, and even Frederick the Great spoke of Russia as a “terrible power” from which, in half a century, “all of Europe will tremble.”

In the last years of her life, the empress lived with concerns about her grandson Alexander, was personally involved in his upbringing and education, and seriously thought about transferring the throne to him, bypassing her son.

Reign of Catherine II

The era of Catherine II is considered the heyday of favoritism. Separated in the early 1770s. with G.G. Orlov, in subsequent years, Empress Catherine replaced a number of favorites (about 15 favorites, among them the talented princes P.A. Rumyantsev, G.A. Potemkin, A.A. Bezborodko). She did not allow them to participate in solving political issues. Catherine lived with her favorites for several years, but parted for a variety of reasons (due to the death of the favorite, his betrayal or unworthy behavior), but no one was disgraced. Everyone was generously awarded ranks, titles, and money.

There is an assumption that Catherine II secretly married Potemkin, with whom she maintained friendly relations until his death.

“Tartuffe in a Skirt and Crown,” nicknamed A.S. Pushkin, Catherine knew how to win people over. She was smart, had political talent, and had a great understanding of people. Outwardly, the ruler was attractive and majestic. She wrote about herself: “Many people say that I work a lot, but it still seems to me that I have done little when I look at what remains to be done.” Such enormous dedication to work was not in vain.

The life of the 67-year-old empress was cut short by a stroke on November 6 (17), 1796 in Tsarskoe Selo. She was buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg.

In 1778, she composed the following epitaph for herself:

Having ascended to the Russian throne, she wished well

And she strongly wanted to give her subjects Happiness, Freedom and Prosperity.

She easily forgave and did not deprive anyone of their freedom.

She was lenient, didn't make life difficult for herself, and had a cheerful disposition.

She had a republican soul and a kind heart. She had friends.

Work was easy for her, friendship and the arts brought her joy.

Catherine's spouses:

- Peter III

- Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin (according to some sources)

- Pavel I Petrovich

- Anna Petrovna

- Alexey Grigorievich Bobrinsky

- Elizaveta Grigorievna Tyomkina

At the end of the 19th century, the collected works of Catherine II the Great were published in 12 volumes, which included children's moral tales written by the empress, pedagogical teachings, dramatic plays, articles, autobiographical notes, and translations.

In cinema, her image is reflected in the films: “Evenings on a farm near Dikanka”, 1961; "Royal Hunt", 1990; “Vivat, midshipmen!”, 1991; “Young Catherine”, 1991; "Russian Revolt", 2000; "Golden Age", 2003; “Catherine the Great”, 2005. Famous actresses played the role of Catherine (Marlene Dietrich, Julia Ormond, Via Artmane, etc.).

Many artists captured the appearance of Catherine II. And works of art clearly reflect the character of the empress herself and the era of her reign (A. S. Pushkin “The Captain’s Daughter”; B. Shaw “The Great Catherine”; V. N. Ivanov “Empress Fike”; V. S. Pikul “The Favorite”, “Pen and Sword”; Boris Akunin “Extracurricular Reading”).

In 1873 monument Catherine II The Great was opened on Alexandrinskaya Square in St. Petersburg. On September 8, 2006, a monument to Catherine II was opened in Krasnodar, on October 27, 2007, monuments to Catherine II Alekseevna were opened in Odessa and Tiraspol. In Sevastopol - May 15, 2008

The reign of Ekaterina Alekseevna is often considered the “golden age” of the Russian Empire. Thanks to her reform activities, she is the only Russian ruler who, like Peter I, was awarded the epithet “Great” in the historical memory of her compatriots.

Empress of All Russia (June 28, 1762 - November 6, 1796). Her reign is one of the most remarkable in Russian history; and its dark and light sides had a tremendous influence on subsequent events, especially on the mental and cultural development of the country. The wife of Peter III, nee Princess of Anhalt-Zerbt (born April 24, 1729), was naturally gifted with a great mind and strong character; on the contrary, her husband was a weak man, poorly brought up. Not sharing his pleasures, Catherine devoted herself to reading and soon moved from novels to historical and philosophical books. A select circle formed around her, in which Catherine’s greatest trust was enjoyed first by Saltykov, and then by Stanislav Poniatovsky, later the King of Poland. Her relationship with Empress Elizabeth was not particularly cordial: when Catherine’s son, Paul, was born, the Empress took the child to her place and rarely allowed the mother to see him. Elizabeth died on December 25, 1761; with the accession of Peter III to the throne, Catherine’s position became even worse. The coup of June 28, 1762 elevated Catherine to the throne (see Peter III). The harsh school of life and enormous natural intelligence helped Catherine herself to get out of a very difficult situation and to lead Russia out of it. The treasury was empty; the monopoly crushed trade and industry; factory peasants and serfs were worried about rumors of freedom, which were renewed every now and then; peasants from the western border fled to Poland. Under such circumstances, Catherine ascended the throne, the rights to which belonged to her son. But she understood that this son would become a plaything on the throne, like Peter II. The regency was a fragile affair. The fate of Menshikov, Biron, Anna Leopoldovna was in everyone’s memory.

Catherine's penetrating gaze stopped equally attentively on the phenomena of life both at home and abroad. Having learned, two months after her accession to the throne, that the famous French Encyclopedia had been condemned by the Parisian parliament for atheism and its continuation was prohibited, Catherine invited Voltaire and Diderot to publish the encyclopedia in Riga. This one proposal won over the best minds, who then gave direction to public opinion throughout Europe, to Catherine’s side. In the fall of 1762, Catherine was crowned and spent the winter in Moscow. In the summer of 1764, Second Lieutenant Mirovich decided to elevate to the throne Ioann Antonovich, the son of Anna Leopoldovna and Anton Ulrich of Brunswick, who was kept in the Shlisselburg fortress. The plan failed - Ivan Antonovich, during an attempt to free him, was shot by one of the guard soldiers; Mirovich was executed by court verdict. In 1764, Prince Vyazemsky, sent to pacify the peasants assigned to the factories, was ordered to investigate the question of the benefits of free labor over hired labor. The same question was proposed to the newly established Economic Society (see Free Economic Society and Serfdom). First of all, the issue of the monastery peasants, which had become especially acute even under Elizabeth, had to be resolved. At the beginning of her reign, Elizabeth returned the estates to monasteries and churches, but in 1757 she, along with the dignitaries around her, came to the conviction of the need to transfer the management of church property to secular hands. Peter III ordered that Elizabeth's instructions be fulfilled and the management of church property be transferred to the board of economy. Inventories of monastery property were carried out, under Peter III, extremely roughly. When Catherine II ascended the throne, the bishops filed complaints with her and asked for the return of control of church property to them. Catherine, on the advice of Bestuzhev-Ryumin, satisfied their desire, abolished the board of economy, but did not abandon her intention, but only postponed its execution; She then ordered that the 1757 commission resume its studies. It was ordered to make new inventories of monastic and church property; but the clergy was also dissatisfied with the new inventories; The Rostov Metropolitan Arseny Matseevich especially rebelled against them. In his report to the synod, he expressed himself harshly, arbitrarily interpreting church historical facts, even distorting them and making comparisons offensive to Catherine. The Synod presented the matter to the Empress, in the hope (as Solovyov thinks) that Catherine II this time will show her usual gentleness. The hope was not justified: Arseny's report caused such irritation in Catherine, which had not been noticed in her either before or since. She could not forgive Arseny for comparing her with Julian and Judas and the desire to make her out to be a violator of her word. Arseny was sentenced to exile to the Arkhangelsk diocese, to the Nikolaev Korelsky Monastery, and then, as a result of new accusations, to deprivation of the monastic dignity and lifelong imprisonment in Revel (see Arseny Matseevich). The following incident from the beginning of her reign is typical for Catherine II. The matter of allowing Jews to enter Russia was reported. Catherine said that to begin her reign with a decree on the free entry of Jews would be a bad way to calm minds; It is impossible to recognize entry as harmful. Then Senator Prince Odoevsky suggested looking at what Empress Elizabeth wrote in the margins of the same report. Catherine demanded a report and read: “I do not want selfish profit from the enemies of Christ.” Turning to the prosecutor general, she said: “I wish this case to be postponed.”

The increase in the number of serfs through huge distributions to the favorites and dignitaries of the populated estates, the establishment of serfdom in Little Russia, completely remains a dark stain on the memory of Catherine II. One should not, however, lose sight of the fact that the underdevelopment of Russian society at that time was evident at every step. So, when Catherine II decided to abolish torture and proposed this measure to the Senate, senators expressed concern that if torture was abolished, no one, going to bed, would be sure whether he would get up alive in the morning. Therefore, Catherine, without abolishing torture publicly, sent out a secret order that in cases where torture was used, judges would base their actions on Chapter X of the Order, in which torture is condemned as a cruel and extremely stupid thing. At the beginning of the reign of Catherine II, an attempt was renewed to create an institution resembling the Supreme Privy Council or the Cabinet that replaced it, in a new form, under the name of the permanent council of the empress. The author of the project was Count Panin. Feldzeichmeister General Villebois wrote to the Empress: “I don’t know who the drafter of this project is, but it seems to me as if, under the guise of protecting the monarchy, he is subtly leaning more towards aristocratic rule.” Villebois was right; but Catherine II herself understood the oligarchic nature of the project. She signed it, but kept it under wraps and it was never made public. Thus Panin's idea of a council of six permanent members remained just a dream; Catherine II's private council always consisted of rotating members. Knowing how Peter III's defection to Prussia irritated public opinion, Catherine ordered Russian generals to remain neutral and thereby contributed to ending the war (see Seven Years' War). The internal affairs of the state required special attention: what was most striking was the lack of justice. Catherine II expressed herself energetically on this matter: “extortion has increased to such an extent that there is hardly the smallest place in the government in which a court would be held without infecting this ulcer; if anyone is looking for a place, he pays; if anyone is defending himself from slander, he defends himself with money; Whether anyone slanderes anyone, he backs up all his cunning machinations with gifts.” Catherine was especially amazed when she learned that within the current Novgorod province they took money from peasants for swearing allegiance to her. This state of justice forced Catherine II to convene a commission in 1766 to publish the Code. Catherine II handed this commission an Order, which it was to be guided by when drawing up the Code. The mandate was drawn up based on the ideas of Montesquieu and Beccaria (see Mandate [ Big] and the Commission of 1766). Polish affairs, the first Turkish war that arose from them, and internal unrest suspended the legislative activity of Catherine II until 1775. Polish affairs caused the divisions and fall of Poland: under the first partition of 1773, Russia received the current provinces of Mogilev, Vitebsk, part of Minsk, i.e. most of Belarus (see Poland). The first Turkish war began in 1768 and ended in peace in Kucuk-Kaynarji, which was ratified in 1775. According to this peace, the Porte recognized the independence of the Crimean and Budzhak Tatars; ceded Azov, Kerch, Yenikale and Kinburn to Russia; opened free passage for Russian ships from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean; granted forgiveness to Christians who took part in the war; allowed Russia's petition in Moldovan cases. During the first Turkish war, a plague raged in Moscow, causing a plague riot; In eastern Russia, an even more dangerous rebellion broke out, known as the Pugachevshchina. In 1770, the plague from the army entered Little Russia; in the spring of 1771 it appeared in Moscow; the commander-in-chief (currently the governor-general) Count Saltykov left the city to the mercy of fate. Retired General Eropkin voluntarily took upon himself the difficult responsibility of maintaining order and easing the plague through preventive measures. The townsfolk did not follow his instructions and not only did not burn the clothes and linen of those who died of the plague, but they hid their very death and buried them in the outskirts. The plague intensified: in the early summer of 1771, 400 people died every day. The people crowded in horror at the Barbarian Gate, in front of the miraculous icon. The infection from crowding of people, of course, intensified. The then Moscow Archbishop Ambrose (q.v.), an enlightened man, ordered the icon to be removed. A rumor immediately spread that the bishop, together with the doctors, had conspired to kill the people. The ignorant and fanatical crowd, mad with fear, killed the worthy archpastor. Rumors spread that the rebels were preparing to set fire to Moscow and exterminate doctors and nobles. Eropkin, with several companies, managed, however, to restore calm. In the last days of September, Count Grigory Orlov, then the closest person to Catherine, arrived in Moscow: but at this time the plague was already weakening and stopped in October. This plague killed 130,000 people in Moscow alone.

The Pugachev rebellion was started by the Yaik Cossacks, dissatisfied with the changes in their Cossack life. In 1773, the Don Cossack Emelyan Pugachev (q.v.) took the name of Peter III and raised the banner of rebellion. Catherine II entrusted the pacification of the rebellion to Bibikov, who immediately understood the essence of the matter; It’s not Pugachev that’s important, he said, it’s the general displeasure that’s important. The Yaik Cossacks and the rebellious peasants were joined by the Bashkirs, Kalmyks, and Kyrgyz. Bibikov, giving orders from Kazan, moved detachments from all sides to more dangerous places; Prince Golitsyn liberated Orenburg, Mikhelson - Ufa, Mansurov - Yaitsky town. At the beginning of 1774, the rebellion began to subside, but Bibikov died of exhaustion, and the rebellion flared up again: Pugachev captured Kazan and moved to the right bank of the Volga. Bibikov's place was taken by Count P. Panin, but did not replace him. Mikhelson defeated Pugachev near Arzamas and blocked his path to Moscow. Pugachev rushed to the south, took Penza, Petrovsk, Saratov and hanged nobles everywhere. From Saratov he moved to Tsaritsyn, but was repulsed and at Cherny Yar was again defeated by Mikhelson. When Suvorov arrived to the army, the impostor barely held on and was soon betrayed by his accomplices. In January 1775, Pugachev was executed in Moscow (see Pugachevshchina). Since 1775, the legislative activity of Catherine II resumed, which, however, had not stopped before. Thus, in 1768, the commercial and noble banks were abolished and the so-called assignat or change bank was established (see Assignations). In 1775, the existence of the Zaporozhye Sich, which was already heading towards collapse, ceased to exist. In the same 1775, the transformation of provincial government began. An institution was published for the management of provinces, which was introduced for twenty whole years: in 1775 it began with the Tver province and ended in 1796 with the establishment of the Vilna province (see Governorate). Thus, the reform of provincial government, begun by Peter the Great, was brought out of the chaotic state by Catherine II and completed by her. In 1776, Catherine ordered the word in petitions slave replace with the word loyal. Towards the end of the first Turkish war, Potemkin, who strove for great things, became especially important. Together with his collaborator, Bezborodko, he compiled a project known as the Greek one. The grandeur of this project - by destroying the Ottoman Porte, restoring the Greek Empire, to the throne of which Konstantin Pavlovich would be installed - pleased E. An opponent of Potemkin's influence and plans, Count N. Panin, tutor of Tsarevich Paul and president of the College of Foreign Affairs, in order to distract Catherine II from the Greek project , presented her with a project of armed neutrality in 1780. Armed neutrality (q.v.) was intended to provide protection to the trade of neutral states during the war and was directed against England, which was unfavorable for Potemkin’s plans. Pursuing his broad and useless plan for Russia, Potemkin prepared an extremely useful and necessary thing for Russia - the annexation of Crimea. In Crimea, since the recognition of its independence, two parties were worried - Russian and Turkish. Their struggle gave rise to the occupation of Crimea and the Kuban region. The Manifesto of 1783 announced the annexation of Crimea and the Kuban region to Russia. The last Khan Shagin-Girey was sent to Voronezh; Crimea was renamed the Tauride province; Crimean raids stopped. It is believed that as a result of the raids of the Crimeans, Great and Little Russia and part of Poland, from the 15th century. until 1788, it lost from 3 to 4 million of its population: captives were turned into slaves, captives filled harems or became, like slaves, in the ranks of female servants. In Constantinople, the Mamelukes had Russian nurses and nannies. In the XVI, XVII and even in the XVIII centuries. Venice and France used shackled Russian slaves purchased in the markets of the Levant as galley laborers. The pious Louis XIV tried only to ensure that these slaves did not remain schismatics. The annexation of Crimea put an end to the shameful trade in Russian slaves (see V. Lamansky in the Historical Bulletin for 1880: “The Power of the Turks in Europe”). Following this, Irakli II, the king of Georgia, recognized the protectorate of Russia. The year 1785 was marked by two important pieces of legislation: Charter granted to the nobility(see nobility) and City regulations(see City). The charter on public schools on August 15, 1786 was implemented only on a small scale. Projects to found universities in Pskov, Chernigov, Penza and Yekaterinoslav were postponed. In 1783, the Russian Academy was founded to study the native language. The founding of the institutions marked the beginning of women's education. Orphanages were established, smallpox vaccination was introduced, and the Pallas expedition was equipped to study the remote outskirts.

Potemkin's enemies interpreted, not understanding the importance of acquiring Crimea, that Crimea and Novorossiya were not worth the money spent on their establishment. Then Catherine II decided to explore the newly acquired region herself. Accompanied by the Austrian, English and French ambassadors, with a huge retinue, in 1787 she set off on a journey. The Archbishop of Mogilev, Georgy Konissky, met her in Mstislavl with a speech that was famous by her contemporaries as an example of eloquence. The whole character of the speech is determined by its beginning: “Let us leave it to the astronomers to prove that the Earth revolves around the Sun: our sun moves around us.” In Kanev, Stanislav Poniatovsky, King of Poland, met Catherine II; near Keidan - Emperor Joseph II. He and Catherine laid the first stone of the city of Yekaterinoslav, visited Kherson and inspected the Black Sea fleet that Potemkin had just created. During the journey, Joseph noticed the theatricality in the situation, saw how people were hastily herded into villages that were supposedly under construction; but in Kherson he saw the real deal - and gave justice to Potemkin.

The Second Turkish War under Catherine II was fought in alliance with Joseph II, from 1787 to 1791. In 1791, on December 29, peace was concluded in Iasi. For all the victories, Russia received only Ochakov and the steppe between the Bug and the Dnieper (see Turkish wars and the Peace of Jassy). At the same time, there was, with varying success, a war with Sweden, declared by Gustav III in 1789 (see Sweden). It ended on August 3, 1790 with the Peace of Verel (see), based on the status quo. During the 2nd Turkish War, a coup took place in Poland: on May 3, 1791, a new constitution was promulgated, which led to the second partition of Poland, in 1793, and then to the third, in 1795 (see Poland). Under the second section, Russia received the rest of the Minsk province, Volyn and Podolia, and under the 3rd - the Grodno Voivodeship and Courland. In 1796, in the last year of the reign of Catherine II, Count Valerian Zubov, appointed commander-in-chief in the campaign against Persia, conquered Derbent and Baku; His successes were stopped by the death of Catherine.

The last years of the reign of Catherine II were darkened, from 1790, by a reactionary direction. Then the French Revolution broke out, and the pan-European, Jesuit-oligarchic reaction entered into an alliance with our reaction at home. Her agent and instrument was Catherine’s last favorite, Prince Platon Zubov, together with his brother, Count Valerian. European reaction wanted to drag Russia into the struggle with revolutionary France - a struggle alien to the direct interests of Russia. Catherine II spoke kind words to the representatives of the reaction and did not give a single soldier. Then the undermining of the throne of Catherine II intensified, and accusations were renewed that she was illegally occupying the throne that belonged to Pavel Petrovich. There is reason to believe that in 1790 an attempt was being made to elevate Pavel Petrovich to the throne. This attempt was probably connected with the expulsion of Prince Frederick of Württemberg from St. Petersburg. The reaction at home then accused Catherine of allegedly being excessively free-thinking. The basis for the accusation was, among other things, permission to translate Voltaire and participation in the translation of Belisarius, Marmontel's story, which was found anti-religious, because it did not indicate the difference between Christian and pagan virtue. Catherine II grew old, there was almost no trace of her former courage and energy - and so, under such circumstances, in 1790 Radishchev’s book “Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow” appeared, with a project for the liberation of the peasants, as if written out from the published articles of her Order. The unfortunate Radishchev was punished by exile to Siberia. Perhaps this cruelty was the result of the fear that the exclusion of articles on the emancipation of peasants from the Order would be considered hypocrisy on the part of Catherine. In 1792, Novikov, who had served so much in Russian education, was imprisoned in Shlisselburg. The secret motive for this measure was Novikov’s relationship with Pavel Petrovich. In 1793, Knyazhnin suffered cruelly for his tragedy "Vadim". In 1795, even Derzhavin was suspected of being in a revolutionary direction, for his transcription of Psalm 81, entitled “To Rulers and Judges.” Thus ended the educational reign of Catherine the Second, which raised the national spirit, this great man(Catherine le grand). Despite the reaction of recent years, the name of educational activity will remain with him in history. From this reign in Russia they began to realize the importance of humane ideas, they began to talk about the right of man to think for the benefit of his own kind. had a great influence on the general course of affairs." Under Catherine, Zubov’s influence was harmful, but only because he was an instrument of a harmful party.].

Literature. The works of Kolotov, Sumarokov, Lefort are panegyrics. Of the new ones, Brickner's work is more satisfactory. Bilbasov's very important work is not finished; Only one volume was published in Russian, two in German. S. M. Solovyov, in the XXIX volume of his history of Russia, focused on peace in Kuchuk-Kainardzhi. The foreign works of Rulière and Custer cannot be ignored only because of undeserved attention to them. Of the countless memoirs, Khrapovitsky's memoirs are especially important (the best edition is by N.P. Barsukova). See Waliszewski's newest work: "Le Roman d"une impératrice". Works on individual issues are indicated in the corresponding articles. The publications of the Imperial Historical Society are extremely important.

E. Belov.

Gifted with literary talent, receptive and sensitive to the phenomena of life around her, Catherine II took an active part in the literature of her time. The literary movement she excited was dedicated to the development of educational ideas of the 18th century. Thoughts on education, briefly outlined in one of the chapters of “Instruction,” were subsequently developed in detail by Catherine in allegorical tales: “About Tsarevich Chlor” (1781) and “About Tsarevich Fevey” (1782), and mainly in “Instructions to Prince N. Saltykov" given upon his appointment as tutor to the Grand Dukes Alexander and Konstantin Pavlovich (1784). Catherine mainly borrowed the pedagogical ideas expressed in these works from Montaigne and Locke: from the first she took a general view of the goals of education, and she used the second when developing particulars. Guided by Montaigne, Catherine II put the moral element in first place in education - the rooting in the soul of humanity, justice, respect for laws, and condescension towards people. At the same time, she demanded that the mental and physical aspects of education be properly developed. Personally raising her grandchildren until the age of seven, she compiled an entire educational library for them. Catherine also wrote “Notes on Russian History” for the Grand Dukes. In purely fictional works, which include magazine articles and dramatic works, Catherine II is much more original than in works of a pedagogical and legislative nature. Pointing out actual contradictions to the ideals that existed in society, her comedies and satirical articles were supposed to significantly contribute to the development of public consciousness, making the importance and expediency of the reforms she was undertaking more clear.

The beginning of Catherine II's public literary activity dates back to 1769, when she became an active collaborator and inspirer of the satirical magazine "Everything and Everything" (see). The patronizing tone adopted by "Everything and Everything" in relation to other magazines, and the instability of its direction, soon armed almost all the magazines of that time against it; her main opponent was the brave and direct “Drone” of N. I. Novikov. The latter's harsh attacks on judges, governors and prosecutors greatly displeased "Everything"; It is impossible to say positively who conducted the polemics against “Drone” in this magazine, but it is reliably known that one of the articles directed against Novikov belonged to the empress herself. In the period from 1769 to 1783, when Catherine again acted as a journalist, she wrote five comedies, and between them her best plays: “About Time” and “Mrs. Vorchalkina’s Name Day.” The purely literary merits of Catherine's comedies are not high: they have little action, the intrigue is too simple, the denouement is monotonous. They are written in the spirit and model of French modern comedies, in which servants are more developed and intelligent than their masters. But at the same time, in Catherine’s comedies, purely Russian social vices are ridiculed and Russian types appear. Hypocrisy, superstition, bad education, the pursuit of fashion, blind imitation of the French - these are the themes that Catherine developed in her comedies. These themes had already been outlined earlier in our satirical magazines of 1769 and, by the way, “Everything and Everything”; but what was presented in magazines in the form of separate pictures, characteristics, sketches, in the comedies of Catherine II received a more complete and vivid image. The types of the stingy and heartless prude Khanzhakhina, the superstitious gossip Vestnikova in the comedy "About Time", the petimeter Firlyufyushkov and the projector Nekopeikov in the comedy "Mrs. Vorchalkina's Name Day" are among the most successful in Russian comic literature of the last century. Variations of these types are repeated in other comedies of Catherine.

By 1783, Catherine’s active participation in the “Interlocutor of Lovers of the Russian Word,” published at the Academy of Sciences, edited by Princess E. R. Dashkova, dates back. Here Catherine II placed a number of satirical articles entitled “Fables and Fables.” The initial purpose of these articles was, apparently, a satirical depiction of the weaknesses and funny aspects of the society contemporary to the empress, and the originals for such portraits were often taken by the empress from among those close to her. Soon, however, “Were and Fables” began to serve as a reflection of the magazine life of “Interlocutor”. Catherine II was the unofficial editor of this magazine; as can be seen from her correspondence with Dashkova, she read many of the articles sent for publication in the magazine while still in manuscript; some of these articles touched her to the quick: she entered into polemics with their authors, often making fun of them. For the reading public, Catherine’s participation in the magazine was no secret; Articles of letters were often sent to the address of the author of Fables and Fables, in which rather transparent hints were made. The Empress tried as much as possible to maintain composure and not give away her incognito identity; only once, enraged by Fonvizin’s “impudent and reprehensible” questions, she so clearly expressed her irritation in “Facts and Fables” that Fonvizin considered it necessary to rush with a letter of repentance. In addition to “Facts and Fables,” the empress placed in “Interlocutor” several small polemical and satirical articles, mostly ridiculing the pompous writings of random collaborators of “Interlocutor” - Lyuboslov and Count S.P. Rumyantsev. One of these articles (“The Society of the Unknowing, a daily note”), in which Princess Dashkova saw a parody of the meetings of the then newly founded, in her opinion, Russian Academy, served as the reason for the termination of Catherine’s participation in the magazine. In subsequent years (1785-1790), Catherine wrote 13 plays, not counting dramatic proverbs in French, intended for the Hermitage theater.

The Masons have long attracted the attention of Catherine II. If you believe her words, she took the trouble to familiarize herself in detail with the vast Masonic literature, but did not find anything in Freemasonry other than “stupidity.” Stay in St. Petersburg. (in 1780) Cagliostro, whom she described as a scoundrel worthy of the gallows, armed her even more against the Freemasons. Receiving alarming news about the increasingly increasing influence of Moscow Masonic circles, seeing among her entourage many followers and defenders of the Masonic teaching, the Empress decided to fight this “folly” with literary weapons, and within two years (1785-86) she wrote one the other, three comedies ("The Deceiver", "The Seduced" and "The Siberian Shaman"), in which Freemasonry was ridiculed. Only in the comedy "The Seduced" are there, however, life traits reminiscent of the Moscow Freemasons. "The Deceiver" is directed against Cagliostro. In “The Shaman of Siberia,” Catherine II, obviously unfamiliar with the essence of Masonic teaching, did not think to bring it on the same level with shamanic tricks. There is no doubt that Catherine’s satire did not have much effect: Freemasonry continued to develop, and in order to deal a decisive blow to it, the empress no longer resorted to meek methods of correction, as she called her satire, but to drastic and decisive administrative measures.

In all likelihood, Catherine’s acquaintance with Shakespeare, in French or German translations, also dates back to this time. She remade The Witches of Windsor for the Russian stage, but this rework turned out to be extremely weak and bears very little resemblance to the original Shakespeare. In imitation of his historical chronicles, she composed two plays from the life of the ancient Russian princes - Rurik and Oleg. The main significance of these “Historical Representations,” which are extremely weak in literary terms, lies in the political and moral ideas that Catherine puts into the mouths of the characters. Of course, these are not the ideas of Rurik or Oleg, but the thoughts of Catherine II herself. In comic operas, Catherine II did not pursue any serious goal: these were situational plays in which the main role was played by the musical and choreographic side. The empress took the plot for these operas, for the most part, from folk tales and epics, known to her from manuscript collections. Only “The Woe-Bogatyr Kosometovich,” despite its fairy-tale character, contains an element of modernity: this opera showed the Swedish king Gustav III, who at that time opened hostile actions against Russia, in a comic light, and was removed from the repertoire immediately after the conclusion of peace with Sweden. Catherine's French plays, the so-called “proverbs,” are small one-act plays, the plots of which were, for the most part, episodes from modern life. They do not have any special significance, repeating themes and types already introduced in other comedies of Catherine II. Catherine herself did not attach importance to her literary activity. “I look at my writings,” she wrote to Grimm, “as trifles. I love to do experiments in all kinds, but it seems to me that everything I wrote is rather mediocre, which is why, apart from entertainment, I did not attach any importance to it.”

Works of Catherine II published by A. Smirdin (St. Petersburg, 1849-50). Exclusively literary works of Catherine II were published twice in 1893, edited by V. F. Solntsev and A. I. Vvedensky. Selected articles and monographs: P. Pekarsky, “Materials for the history of the journal and literary activities of Catherine II” (St. Petersburg, 1863); Dobrolyubov, st. about the “Interlocutor of lovers of the Russian word” (X, 825); "Works of Derzhavin", ed. J. Grota (St. Petersburg, 1873, vol. VIII, pp. 310-339); M. Longinov, “Dramatic works of Catherine II” (M., 1857); G. Gennadi, “More about the dramatic writings of Catherine II” (in “Biblical Zap.”, 1858, No. 16); P. K. Shchebalsky, “Catherine II as a Writer” (Zarya, 1869-70); his, “Dramatic and morally descriptive works of Empress Catherine II” (in “Russian Bulletin”, 1871, vol. XVIII, nos. 5 and 6); N. S. Tikhonravov, “Literary trifles of 1786.” (in the scientific and literary collection, published by "Russkie Vedomosti" - "Help to the Starving", M., 1892); E. S. Shumigorsky, “Essays from Russian history. I. Empress-publicist” (St. Petersburg, 1887); P. Bessonova, “On the influence of folk art on the dramas of Empress Catherine and on the integral Russian songs inserted here” (in the magazine “Zarya”, 1870); V. S. Lebedev, “Shakespeare in the adaptations of Catherine II” (in the Russian Bulletin) (1878, No. 3); N. Lavrovsky, “On the pedagogical significance of the works of Catherine the Great” (Kharkov, 1856); A. Brickner, “Comic Opera Catherine II "Woe-Bogatyr" ("J.M.N. Pr.", 1870, No. 12); A. Galakhov, "There were also Fables, the work of Catherine II" ("Notes of the Fatherland" 1856, No. 10).

V. Solntsev.

“Her reign was successful. As a conscientious German, Catherine worked diligently for the country that gave her such a good and profitable position. She naturally saw the happiness of Russia in the greatest possible expansion of the boundaries of the Russian state. By nature she was smart and cunning, well versed in the intrigues of European diplomacy. Cunning and flexibility were the basis of what in Europe, depending on the circumstances, was called the policy of Northern Semiramis or the crimes of Moscow Messalina.” (M. Aldanov “Devil's Bridge”)

Years of reign of Russia by Catherine the Great 1762-1796

Catherine the Second's real name was Sophia Augusta Frederika of Anhalt-Zerbst. She was the daughter of the Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst, the commandant of the city of Stettin, which was located in Pomerania, a region subject to the Kingdom of Prussia (today the Polish city of Szczecin), who represented “a side line of one of the eight branches of the house of Anhalst.”

“In 1742, the Prussian king Frederick II, wanting to annoy the Saxon court, which hoped to marry his princess Maria Anna to the heir to the Russian throne, Peter Karl-Ulrich of Holstein, who suddenly became Grand Duke Peter Fedorovich, began hastily looking for another bride for the Grand Duke.

The Prussian king had three German princesses in mind for this purpose: two from Hesse-Darmstadt and one from Zerbst. The latter was the most suitable in age, but Friedrich knew nothing about the fifteen-year-old bride herself. They only said that her mother, Johanna Elisabeth, led a very frivolous lifestyle and that it is unlikely that little Fike was really the daughter of the Zerbst prince Christian Augustus, who served as governor in Stetin.”

How long, short, but in the end the Russian Empress Elizaveta Petrovna chose little Fike as a wife for her nephew Karl-Ulrich, who became Grand Duke Peter Fedorovich in Russia, the future Emperor Peter III.

Biography of Catherine II. Briefly

- 1729, April 21 (Old style) - Catherine the Second was born

- 1742, December 27 - on the advice of Frederick II, the mother of Princess Ficken (Fike) sent a letter to Elizabeth with New Year congratulations

- 1743, January - kind reply letter

- 1743, December 21 - Johanna Elisabeth and Ficken received a letter from Brumner, the teacher of Grand Duke Peter Fedorovich, with an invitation to come to Russia

“Your Grace,” Brummer wrote meaningfully, “are too enlightened not to understand the true meaning of the impatience with which Her Imperial Majesty wishes to see you here as soon as possible, as well as your princess daughter, about whom rumor has told us so many good things.”

- 1743, December 21 - on the same day a letter from Frederick II was received in Zerbst. The Prussian king... persistently advised to go and keep the trip strictly secret (so that the Saxons would not find out ahead of time)

- 1744, February 3 - German princesses arrived in St. Petersburg

- 1744, February 9 - the future Catherine the Great and her mother arrived in Moscow, where the court was located at that moment

- 1744, February 18 - Johanna Elisabeth sent a letter to her husband with the news that their daughter was the bride of the future Russian Tsar

- 1745, June 28 - Sofia Augusta Frederica converted to Orthodoxy and new name Catherine

- 1745, August 21 - marriage of Catherine

- 1754, September 20 - Catherine gave birth to a son, heir to the throne Paul

- 1757, December 9 - Catherine gave birth to a daughter, Anna, who died 3 months later

- 1761, December 25 - Elizaveta Petrovna died. Peter the Third became Tsar

“Peter the Third was the son of the daughter of Peter I and the grandson of the sister of Charles XII. Elizabeth, having ascended the Russian throne and wanting to secure it behind her father’s line, sent Major Korf with instructions to take her nephew from Kiel and deliver him to St. Petersburg at all costs. Here the Holstein Duke Karl-Peter-Ulrich was transformed into Grand Duke Peter Fedorovich and forced to study the Russian language and the Orthodox catechism. But nature was not as favorable to him as fate... He was born and grew up as a frail child, poorly endowed with abilities. Having become an orphan at an early age, Peter in Holstein received a worthless upbringing under the guidance of an ignorant courtier.

Humiliated and embarrassed in everything, he acquired bad tastes and habits, became irritable, cantankerous, stubborn and false, acquired a sad inclination to lie..., and in Russia he also learned to get drunk. In Holstein he was taught so poorly that he came to Russia as a 14-year-old complete ignoramus and even amazed Empress Elizabeth with his ignorance. The rapid change of circumstances and educational programs completely confused his already fragile head. Forced to learn this and that without connection and order, Peter ended up learning nothing, and the dissimilarity of the Holstein and Russian situations, the meaninglessness of the Kiel and St. Petersburg impressions completely weaned him from understanding his surroundings. ...He was fascinated by the military glory and strategic genius of Frederick II...” (V. O. Klyuchevsky “Course of Russian History”)

- 1761, April 13 - Peter made peace with Frederick. All lands seized by Russia from Prussia during the course were returned to the Germans

- 1761, May 29 - union treaty between Prussia and Russia. Russian troops were transferred to the disposal of Frederick, which caused sharp discontent among the guards

(The flag of the guard) “became the empress. The emperor lived badly with his wife, threatened to divorce her and even imprison her in a monastery, and in her place put a person close to him, the niece of Chancellor Count Vorontsov. Catherine stayed aloof for a long time, patiently enduring her situation and not entering into direct relations with the dissatisfied.” (Klyuchevsky)

- 1761, June 9 - at the ceremonial dinner on the occasion of the confirmation of this peace treaty, the emperor proposed a toast to the imperial family. Catherine drank her glass while sitting. When Peter asked why she did not stand up, she replied that she did not consider it necessary, since the imperial family consists entirely of the emperor, herself and their son, the heir to the throne. “And my uncles, the Holstein princes?” - Peter objected and ordered Adjutant General Gudovich, who was standing behind his chair, to approach Catherine and say a swear word to her. But, fearing that Gudovich might soften this uncivil word during the transfer, Peter himself shouted it across the table for all to hear.

The Empress burst into tears. That same evening it was ordered to arrest her, which, however, was not carried out at the request of one of Peter’s uncles, the unwitting culprits of this scene. From that time on, Catherine began to listen more attentively to the proposals of her friends, which were made to her, starting from the very death of Elizabeth. The enterprise was sympathized with by many people from high society in St. Petersburg, most of whom were personally offended by Peter

- 1761, June 28 - . Catherine is proclaimed empress

- 1761, June 29 - Peter the Third abdicated the throne

- 1761, July 6 - killed in prison

- 1761, September 2 - Coronation of Catherine II in Moscow

- 1787, January 2-July 1 -

- 1796, November 6 - death of Catherine the Great

Domestic policy of Catherine II

-

Changes in central government: in 1763, the structure and powers of the Senate were streamlined

-

Liquidation of the autonomy of Ukraine: liquidation of the hetmanate (1764), liquidation of the Zaporozhye Sich (1775), serfdom of the peasantry (1783)

-

Further subordination of the church to the state: secularization of church and monastic lands, 900 thousand church serfs became state serfs (1764)

-

Improving legislation: a decree on tolerance for schismatics (1764), the right of landowners to send peasants to hard labor (1765), the introduction of a noble monopoly on distilling (1765), a ban on peasants filing complaints against landowners (1768), the creation of separate courts for nobles, townspeople and peasants (1775), etc.

-

Improving the administrative system of Russia: dividing Russia into 50 provinces instead of 20, dividing provinces into districts, dividing power in provinces by function (administrative, judicial, financial) (1775);

-

Strengthening the position of the nobility (1785):

- confirmation of all class rights and privileges of the nobility: exemption from compulsory service, from poll tax, corporal punishment; the right to unlimited disposal of estate and land together with the peasants;

- the creation of noble estate institutions: district and provincial noble assemblies, which met once every three years and elected district and provincial leaders of the nobility;

- assigning the title of “noble” to the nobility.

“Catherine the Second well understood that she could stay on the throne only by pleasing the nobility and officers in every possible way - in order to prevent or at least reduce the danger of a new palace conspiracy. This is what Catherine did. Her entire internal policy boiled down to ensuring that the life of the officers at her court and in the guards units was as profitable and pleasant as possible.”

- Economic innovations: establishment of a financial commission to unify money; establishment of a commission on commerce (1763); manifesto on the general demarcation to fix land plots; establishment of the Free Economic Society to assist noble entrepreneurship (1765); financial reform: introduction of paper money - assignats (1769), creation of two assignat banks (1768), issue of the first Russian external loan (1769); establishment of the postal department (1781); permission for private individuals to open a printing house (1783)

Foreign policy of Catherine II

- 1764 - Treaty with Prussia

- 1768-1774 — Russian-Turkish War

- 1778 - Restoration of the alliance with Prussia

- 1780 - union of Russia and Denmark. and Sweden for the purpose of protecting navigation during the American Revolutionary War

- 1780 - Defensive Alliance of Russia and Austria

- 1783, April 8 -

- 1783, August 4 - establishment of a Russian protectorate over Georgia

- 1787-1791 —

- 1786, December 31 - trade agreement with France

- 1788 June - August - war with Sweden

- 1792 - severance of relations with France

- 1793, March 14 - Treaty of Friendship with England

- 1772, 1193, 1795 - participation together with Prussia and Austria in the partitions of Poland

- 1796 - war in Persia in response to the Persian invasion of Georgia

Personal life of Catherine II. Briefly

“Catherine, by nature, was neither evil nor cruel... and overly power-hungry: all her life she was invariably under the influence of successive favorites, to whom she gladly ceded her power, interfering in their disposal of the country only when they very clearly showed their inexperience, inability or stupidity: she was smarter and more experienced in business than all her lovers, with the exception of Prince Potemkin.

There was nothing excessive in Catherine’s nature, except for a strange mixture of the coarsest sensuality that grew stronger over the years with purely German, practical sentimentality. At sixty-five years old, she, as a girl, fell in love with twenty-year-old officers and sincerely believed that they were also in love with her. In her seventh decade, she cried bitter tears when it seemed to her that Platon Zubov was more reserved with her than usual.”(Mark Aldanov)

A foreigner by birth, she sincerely loved Russia and cared about the welfare of her subjects. Having taken the throne through a palace coup, the wife of Peter III tried to implement the best ideas of the European Enlightenment into the life of Russian society. At the same time, Catherine opposed the outbreak of the Great French Revolution (1789-1799), outraged by the execution of the French king Louis XVI of Bourbon (January 21, 1793) and predetermining Russia's participation in the anti-French coalition of European states at the beginning of the 19th century.

Catherine II Alekseevna (nee Sophia Augusta Frederica, Princess of Anhalt-Zerbst) was born on May 2, 1729 in the German city of Stettin (modern territory of Poland), and died on November 17, 1796 in St. Petersburg.

The daughter of Prince Christian August of Anhalt-Zerbst, who was in the Prussian service, and Princess Johanna Elisabeth (née Princess Holstein-Gottorp), she was related to the royal houses of Sweden, Prussia and England. She received a home education, the course of which, in addition to dance and foreign languages, also included the basics of history, geography and theology.

In 1744, she and her mother were invited to Russia by Empress Elizaveta Petrovna, and baptized according to Orthodox custom under the name of Ekaterina Alekseevna. Soon her engagement to Grand Duke Peter Fedorovich (future Emperor Peter III) was announced, and in 1745 they got married.

Catherine understood that the court loved Elizabeth, did not accept many of the oddities of the heir to the throne, and, perhaps, after Elizabeth’s death, it was she who, with the support of the court, would ascend to the Russian throne. Catherine studied the works of figures of the French Enlightenment, as well as jurisprudence, which had a significant impact on her worldview. In addition, she made as much effort as possible to study, and perhaps understand, the history and traditions of the Russian state. Because of her desire to know everything Russian, Catherine won the love of not only the court, but also the whole of St. Petersburg.

After the death of Elizaveta Petrovna, Catherine’s relationship with her husband, never distinguished by warmth and understanding, continued to deteriorate, taking on clearly hostile forms. Fearing arrest, Ekaterina, with the support of the Orlov brothers, N.I. Panina, K.G. Razumovsky, E.R. Dashkova, on the night of June 28, 1762, when the emperor was in Oranienbaum, carried out a palace coup. Peter III was exiled to Ropsha, where he soon died under mysterious circumstances.

Having begun her reign, Catherine tried to implement the ideas of the Enlightenment and organize the state in accordance with the ideals of this most powerful European intellectual movement. Almost from the first days of her reign, she has been actively involved in government affairs, proposing reforms that are significant for society. On her initiative, a reform of the Senate was carried out in 1763, which significantly increased the efficiency of its work. Wanting to strengthen the dependence of the church on the state, and to provide additional land resources to the nobility supporting the policy of reforming society, Catherine carried out the secularization of church lands (1754). The unification of administration of the territories of the Russian Empire began, and the hetmanate in Ukraine was abolished.

A champion of Enlightenment, Catherine creates a number of new educational institutions, including for women (Smolny Institute, Catherine School).

In 1767, the Empress convened a commission, which included representatives of all segments of the population, including peasants (except serfs), to compose a new code - a code of laws. To guide the work of the Legislative Commission, Catherine wrote “The Mandate,” the text of which was based on the writings of educational authors. This document, in essence, was the liberal program of her reign.

After the end of the Russian-Turkish war of 1768-1774. and the suppression of the uprising under the leadership of Emelyan Pugachev, a new stage of Catherine’s reforms began, when the empress independently developed the most important legislative acts and, taking advantage of the unlimited power of her power, put them into practice.

In 1775, a manifesto was issued that allowed the free opening of any industrial enterprises. In the same year, a provincial reform was carried out, which introduced a new administrative-territorial division of the country, which remained until 1917. In 1785, Catherine issued letters of grant to the nobility and cities.

In the foreign policy arena, Catherine II continued to pursue an offensive policy in all directions - northern, western and southern. The results of foreign policy can be called the strengthening of Russia's influence on European affairs, three sections of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, strengthening of positions in the Baltic states, annexation of Crimea, Georgia, participation in countering the forces of revolutionary France.

The contribution of Catherine II to Russian history is so significant that her memory is preserved in many works of our culture.