And half a mina" (measures of weight), in Church Slavonic texts " mene, tekel, fares") - according to the Old Testament Book of the Prophet Daniel - words inscribed on the wall by a mysterious hand during the feast of the Babylonian king Belshazzar shortly before the fall of Babylon at the hands of Cyrus. The explanation of this sign caused difficulties among the Babylonian sages, but the prophet Daniel was able to explain them:

That same night Belshazzar was killed, and Babylon came under the rule of the Persians (Book of the Prophet Daniel, Chapter 5, Art. 30). Probably, the biblical story is based on real events that accompanied the entry of the Persian army into Babylon on the night of October 12, 539 BC. e.

In secular culture

In secular culture, these words have become a shorthand for foreshadowing the death of eminent persons.

- The lyrics of the song “You Fell as a Victim” (1870-1880), which later became one of the most performed Soviet ideologically significant songs, contains a direct reference to the corresponding fragment of the biblical text: “But the menacing letters have long been on the wall / Already the fatal hand is drawing! "

- In A. Dumas’s novel “The Count of Monte Cristo”: “Each line glowed with fiery letters on the wall, like Belshazzar’s “Mene, Tekel, Fares.”

- In Nikos Zervas's story Children vs. Wizards, the genie Mennetekel is present, giving people inspiration to sing the praises of a strong personality.

- In the third part of Pink Floyd's song Another Brick in the Wall, the words "I have seen the writing on the wall" are heard.

- Ivan Nazhivin’s novel, the writer’s reaction to the events of the Revolution of 1905-1907, was called “Mene... tekel... fares...” (1907).

- In the detective story “The Snowman” by Norwegian author Jo Nesbø, Chief Inspector Harry Hole talks to his lover about their relationship. His straightforward response is compared to "the menacing 'Mene, tekel, fares' inscribed on a bedroom wall."

- “Mene, Tekel, Fares” is the title of a story (“summary of a novel”) by Russian writer Olesya Nikolaeva about modern trends in Orthodoxy.

- G. L. Oldie's novel "Tirman" features the main character Daniel, who tries to compare what is happening around him with the biblical story of King Belshazzar. These words are the key.

- In Andrei Tarkovsky’s film “Stalker” the words “Mene, mene, tekel, uparsin” are heard in the Writer’s monologue about the Professor; in this case, these words are given meaning - calculated, measured, verified.

- Parts of Mikhail Weller’s book “B. Babylonian" have names: "Mene", "Tekel", "Fares".

- In Viktor Pelevin’s novel Chapaev and Emptiness, “mene tekel fares” appeared as an acrostic poem from an article about the dispersal of the Duma.

- In Venedikt Erofeev’s poem “Moscow - Petushki” - in the chapter “Petushki. Garden Ring road": " Mene, tekel, fares- that is, “you are weighed on the scales and found light.”

- In Rostislav Chebykin's song (Filigon) "Life Principles" "MENE, TEKEL, UPARSI" appears as a mysterious inscription on the wall.

- In Timur Shaov’s song “About People’s Love”: “He wrote with lipstick on the wall of the tavern: mene, mene, tekel, uparsin.”

- In the song of the Casta group “Feast” there is a description of the scene with the appearance of the inscription and its implementation.

- In an ironic vein, the formidable biblical prophecy is rethought by such Russian authors of modern times as Dmitry Aleksandrovich Prigov, in whose poems “an illiterate man sings “mene, tekel, fares” to the tune of “oh you canopy, my canopy,” Yuliy Gugolev and others. Ironic signed reviews M. Uparsin appeared in a number of publications.

- In Dmitry Yemets’s book “The Staff of the Magi,” Isadora, the wife of General Kotletkin, trying to take possession of Durnev’s apartment, thinks to herself the phrase about the latter, “You are weighed on the scales and found very light...”.

- In the book “Guest from the Hell” by Ilona Volynskaya and Kirill Kashcheev, Irka Khortitsa’s grandmother, having heard that her daughter saw threatening inscriptions on the gate, ironically quotes: “Before she was a psychopath, but now she’s still imagining troubles! Paintings on the walls! “Mene, tekel, fares.”

- In V.V. Nabokov’s novel “King, Queen, Jack,” a crazy old man who rented a room to Franz called himself: “an excellent magician, Menetekelfares...”.

- In the song “Weighed” by the group “SBPC” in a duet with Nadezhda Gritskevich: “You are weighed on the scales, found very light.”

- In Cassandra Clare's book The Mortal Instruments. City of Glass. The main villain Valentin says: “Mene, mene, tekel, upharsin”

- In the song by Donovan (Donovan Phillips Leach) Universal Soldier: “...He's the one who must decide, who's to live and who's to die, and he never sees the writing on the wall...” (“He alone decides who lives and who dies , and he didn't see the writing on the wall").

- In Alexey Romanov’s song (Sunday) “Do your job” there is a metaphorical phrase: “weighed, measured, counted.”

- Alexander Polezhaev’s poem “Belshazzar” presents the author’s interpretation of the scene with an inscription - a sign of the end of the kingdom.

- In the movie A Knight's Tale, Count Adhemar's favorite line was: "You were weighed, you were measured, and you were found worthless."

- In Igor Bely’s song “Fish Patrol” there is a mysterious inscription “Mene, tekel, tire service.”

- The song "Mane-Tekel-Fares" as part of the album My Guardian Anger performed by the Polish metal band Lux Occulta (1999).

The biblical expression “Mene, mene, tekel, upharsin (mene, tekel, fares)” served as the basis for the stable phrases “weighed, measured, assessed” and “weighed, measured and found unworthy” (worthless, lightweight and etc.)" .

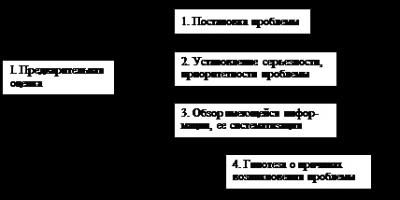

“Mene, mene, tekel, upharsin” or “mene, tekel, fares” (literal translation - “mina, mina, shekel and half a mina”) - words inscribed in letters of fire on the wall during the feast of the Babylonian king Belshazzar. The prophet Daniel was able to explain these words, and they did not promise anything good.

Warning about decadence, sin, moral decline

The character of Karel Capek laments the decline in morals of humanity feasting and rushing into the abyss. Write what he compared the illuminated signs above the entrances to brothels to.

Answer: Mene, tekel, fares.

Test:

A comment: Words inscribed on the wall by a mysterious hand during the feast of the Babylonian king Belshazzar shortly before the fall of Babylon. “Do you want to read the fatal words “mene-tekel-fares”, inscribed in fiery signs over the feasting humanity? Look at the light inscriptions burning all night over the entrances to the dens of revelry and debauchery.”

Biblical expression

It should be one of the first to come when searching through phrases from the Bible (Old Testament).

Describing the death of the Martian civilization, the poet Sergei Orlov notes that three actions were done to the planet, mentioned in the winged biblical saying. Name the person to whom, according to the Bible, this saying was addressed.

Answer: Belshazzar.

A comment: In the poem, the poet writes: “Red Mars was numbered, weighed and measured and drawn to the bottom...”; “Numbered, weighed, measured” - “Mene, mene, tekel, fares” - said the words on the wall of Belshazzar’s palace on the night of the death of his kingdom.

Source: Cybernetic Pegasus. - L.: Children's literature, 1989. - P. 220.

Just three words

Usually with a hint that the words are ancient, incomprehensible, or simply somehow special.

Answer: Mene, tekel, fares.

Test: Mene, tekel, peres; mene, tekel, upharsin.

Mene, mene, tekel, upharsin

In the middle of Belshazzar's feast, during which the holy vessels of the temple were desecrated:

Dan. 5:5. At that very hour the fingers of a human hand came out and wrote against the lamp on the mortar of the wall of the royal palace...

These words were illegible, so Daniel, the now elderly interpreter of Nebuchadnezzar's dreams, was sent for, and his interpretation was as follows:

Dan. 5:25–28. And this is what is written: MENE, MENE, TEKEL, UPHARSIN. This is the meaning of the words: ME - God has numbered your kingdom and put an end to it; TEKEL - you are weighed on the scales and found very light; PERES - your kingdom is divided and given to the Medes and Persians.”

The actual meaning of "mene, mene, tekel, upharsin" is unclear, but these are apparently Aramaic words and may represent the names of measures of weight. Mene is a mina, which is the approximate equivalent of the modern pound, and tekel is a shekel, which is a fiftieth of a mina or a third of an ounce. Upharsin is more mysterious. The Revised Standard Version replaces it with "parsin" and this may be a play on words related to "Parsa" - the native word for what we call Persia. Some believe that Upharsin is a form of a word that originally meant half a shekel.

In any case, the inscription, composed of the names of weights, may have given the impression that God weighed the value of Chaldea against Persia and found that Chaldea was “found very light,” that is, twice as light. This is reminiscent of the scenes in the Greek epic Iliad where Zeus consults the Fates, placing many representatives of the two opposing sides on separate scales to see who outweighs whom. This may have been the source of the vision of God weighing Belshazzar on the scales.

It was this dramatic event that gave rise to the common phrase "a mark on the wall", meaning some indication of imminent disaster, despite even apparent success.

From the book “Behold the Lilies of the Field...” Course of lectures on liturgical theology by Kern CyprianDo not cry for Me, Mother (Friday) All services of the Holy Orthodox Church with all universal purity and clarity reveal the dogmatic meaning and significance of the personality of the Most Holy Theotokos; but the liturgical concept of the Most Pure Virgin is revealed with particular completeness and

From the book of St. Basil the Great. Creations. Part 3 author Great VasilyIn response to the words: “My sick Father is not Me” (John 14:28) The greater is called greater, either in size, or in time, or in dignity, or in strength, or as a reason. But it cannot be said that the Father is greater in size than the Son; because it is incorporeal. But no more and in time; for the Son is the Creator

From the book And There Was Morning... Memories of Father Alexander Men author Team of authorsAND IT WAS MORNING... Memories of Father Alexander Mena And at the top - the Cross. (O. Ignatius Krekshin) When a traveler walks along the road and there is very little left for him to reach his intended goal, but the day is drawing to a close - now twilight is already descending on the earth - will he really look back at

From the book Memories of Fr. Alexandra Mene author Fainberg Vladimir LvovichIt has become fashionable to proclaim the “end times” of Russian literature. There are many reasons for the “decline”: television, the Internet, the low level of current education, a long ruble, in pursuit of which there is no time to read... And most importantly, the lack of criteria for distinguishing between good and evil, beauty and ugliness, real and fictional among both readers and writers . In search of “eternal truths,” the reading public “emigrates” to the classics, completely forgetting that the literature of the 19th century was written one way or another within the Orthodox tradition. It is this, and not abstract “eternal values”, that is its “golden ratio”. It is precisely this foundation that modern Russian literature lacks for the most part. Therefore, the appearance of a talented book written by an Orthodox person is a significant fact in both literary and church life.

In 2003, the Eksmo publishing house published a book of prose by Olesya Nikolaeva, Mene, Tekel, Fares. The novel that gives the collection its title, the story “Disabled Childhood,” and the stories are united by an “unusual” theme: the life of the modern Orthodox Church. But before we start talking about the novel "Mene, Tekel, Fares", it is worth talking about the author himself.

Olesya Alexandrovna was born on June 6, 1955. The first period of her creative biography, and accordingly most of her life, became a “test of strength” for her, as well as for many modern writers who experienced a change in historical eras. Olesya Nikolaeva went through this stage twice: as a bright poetess who did not fit into the framework of the official literary canon, and as a person professing Orthodoxy. She passed, sharing with her husband, a former journalist, and now a priest, Vladimir Vigilyansky, both the hardships of the life of “unreliable” writers and the joys of spiritual work.

Today Olesya Nikolaeva cannot be called only a poet or writer. What she does is more correctly described as literary, church, and social activities. Since 1989, she has been teaching at the department of literary excellence at the Literary Institute, being the head of a creative poetry seminar. In 1989-1990, she gave a course of lectures on “The History of Russian Religious Thought.” In 1990-1994, she traveled at the invitation of New York University, Geneva University and the Sorbonne to give poetry and lectures in New York, Geneva and Paris, taught ancient Greek to the monks-icon painters of the Pskov-Pechersky Monastery, in 1995 she worked as a driver for Abbess Seraphim (Chernaya) in the Novodevichy Convent. In 1998, she was invited to the Theological University of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian to teach the course “Orthodoxy and Creativity” and head the department of journalism.

Olesya Nikolaeva has published six poetry collections and two books of prose. She is the author of two books of religious essays, numerous literary critical essays, and journalistic articles on cultural issues. Her work has been translated into English, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Chinese and other languages. The last novel, “Mene, Tekel, Fares,” which will be discussed, received the Znamya magazine award for 2003.

The novel “Mene, Tekel, Fares” is about the life (or rather, from the life) of Orthodox monks. As the publishers rightly emphasize, it is about the life of “the most neglected prose category of our contemporaries.” For an unchurched, but caring person, this is a book-opening, immersing in the world of people for whom life has an enduring meaning, but who have no less problems and difficulties because of this. For those who are part of church unity, Olesya Nikolaeva’s book is an intelligent view of a believer on the events taking place in the Church. And the main thing is a sincere reflection on how difficult it is to maintain love in the era of “cooling love”, how easy it is to lose it.

An indicator of the “need” and “interest” of a work is the “amplitude of fluctuations” in the opinions of readers and critics. There are no neutral judgments regarding “Mene, tekel, fares”. There are: “A smart, funny and daring book,” “This has never happened before!”, and along with this: “The author, without a sense of truth...”, “A terrible work.” The main accusation is “political incorrectness.” The novel is written in the wake of real events, its characters are recognizable, and its style is unexpected. Its name was taken from the biblical Book of the Prophet Daniel: “Mene, tekel, fares” (which means: “Numbered. Weighed. Divided”), but it was written in an interesting and funny way. Olesya Nikolaeva’s style of narration is often and appropriately compared to Dovlatov and Leskov. What ideological critics call the author’s “political incorrectness” is more correctly called a “point of view” - sincerely experienced, strictly reflected and stylistically brilliantly presented.

It turns out that for a writer’s notebook, the inhabitants and guests of the Holy Trinity Monastery are no less fertile material than the employees of the editorial office or literary museum. As Olesya Nikolaeva herself says: “The hero who constantly appears both in my prose and in poetry is an extremely simple-minded, naive person who does not understand many things at all, can even act like a fool, loves to throw out some trick or joke.” . Just look at the appearance of the American Nancy, who came to the monastery in all seriousness to look for an “environmentally friendly” father for her child! Or the “brothers” who at all costs want to bury their “sidekick” Vitaly in the monastery caves. Absurd realities, which Russian reality does not skimp on and which, if desired, could become the plot of a dark narrative, in Olesya Nikolaeva’s “performance” are recognizable, but not scary, and therefore, with God’s help, surmountable.

The style and humor in the novel turn out to be the landscape for a serious conversation about the life of the Church. The main character of the work, Abbot Herm, an icon painter and theologian, is both talented and fickle. In search of his “own” path, he falls first into the Old Believers, then into reformism, then into Catholicism. Each time he takes his passion to the point of absurdity, not noticing how his spiritual children suffer from this, how form becomes an end in itself, and pride takes the place of love. Following the trajectory of hegumen Erma, Olesya Nikolaeva, with kind irony, writes a chronicle of mistakes and a quotation book of common misconceptions: someone is used to being in opposition and cannot help but organize a riot on the ship, even if it is the Ark of the Covenant, someone is tired of thinking and falls into good-naturedness .

One of the most dramatic places in the novel is the chapter “Orthodoxosis”. It talks about the conflict with the reformers of the Church “Lavrishchevites” (they are easily recognized as followers of the priest Georgy Kochetkov). Their struggle with the “orthodox” Philip for the Moscow Nativity Monastery is being conducted according to the rules of Soviet persecution: with devastating articles in the press and compulsory psychiatric hospitalization. The “good intention” to make the Church “intelligent” turns into provocation, deception and obscurantism.

But it is unlikely that the purpose of the book was to collect problems and “sharp corners.” The monks about whom the novel is written are the most tempted and most responsible people. Responsible for the preservation of Love in our sinful world... And this Love is higher than any principled point of view and greater than absurd reality.

We managed to ask how Olesya Aleksandrovna herself sees her novel.

Olesya Aleksandrovna, what caused the appearance of this unusual, one-of-a-kind novel? Agree that its topic is at least unusual...

I wrote this novel for the reason that I could not help but write it: it required me to sit up at night and pull it out of oblivion into the light of God. Sometimes I myself was surprised at what appeared on paper. At some point I suddenly became confused: is it possible to write so freely about a monastery and monks? I even disturbed Archimandrite Kirill (Pavlov) for the sake of this wonderful and respected elder, and he answered me in the most amazing way for me: “Write as inspiration tells you.” After such a blessing, my novel, which somehow “failed” and “did not line up,” suddenly, as I worked, began to acquire a structure that allowed me to continue writing it.

Can your novel be called a chronicle of church life in recent years, or is it a novel about the difficulties of repentance and finding love?

I think that this is a novel about love for our Creator and Provider, for our Lord, Who in the rite of Baptism is called “A Fair Artist,” which is why he builds every human life according to certain artistic laws.

Why did you take well-known events, famous among religious figures, characters, and people as the plot of the novel? Wouldn’t it be easier to focus on the life of a single monastery, an icon-painting monastery, for example?

If we talk about my novel plots, they seem to me to be very rich in comprehension and characteristic of modern life: the invasion of secular motives into church life, of worldly mentality into monastic life... Well, after so many years of Bolshevik persecution of the Church, this is quite understandable and fixable . In addition, I was amazed that in recent years of church freedom, several Orthodox priests converted to Catholicism. A change of confession between the governor of a monastery and the rector of a Moscow church, you see, is in itself a drama, a conflict, hot food for literature.

If we talk about the prototypes of the heroes of “Mene, Tekel, Fares” and the “partially documentary” aspect - who is who in the novel?

There are many autobiographical elements in the novel, however, there is also a lot of fiction, including fictional characters. And although they have some features of recognizable prototypes, almost all of them represent a kind of alloy of several people, that is, they are collective images. The playwright Strelbitsky, whom for some reason some of my readers and critics identify with Bulat Shalvovich Okudzhava, contains several people, and his story contains several stories that have nothing to do with the real poet. Also “two-part” and my favorite hero is Hierodeacon Dionysius.

But if we talk in general about prototypes in literature, then not a single worthwhile novel can do without them, the main condition of which (as opposed to a story) is the discovery of new characters, the creation of new heroes. Even behind the fictional hero of the novel there are shadows of real people. There are simply prototypes “in their pure” form and recognizable, like, say, Karmazinov (Turgenev), Foma Fomich Opiskin (Gogol), elder Semyon Yakovlevich (the famous Moscow holy fool Ivan Yakovlevich Koreisha) in Dostoevsky, and there are hidden prototypes. I’m now writing a novel about the collapse of an intelligent, talented, charming, but completely groundless unbeliever, and although my hero is fictional, I feel like the words, habits, habits, actions, ideas of my very real acquaintances “flock” to him.

The title of your novel is “Mene, tekel, fares”, mysterious letters from the Book of the Prophet Daniel... One of the heroes of the novel, both in the border detachment and in the monastery, prefers Ukrainian and Chinese to Russian... The French monk Gabriel, who converted to Orthodoxy, in a remote village composes sermons for Russian "grandmothers" in their native language... The conversations of the "Lavrishchevites" remind the reader of "newspeak", consisting of poorly understood Christian vocabulary and Soviet clichés... At the same time, the magnificent style and language of the narrative of your work is at times associated with the style and language of Leskov and Dovlatov. Can we say that another hero of the novel is the modern Russian language, where all meanings have been erased like an old sole? The "high and mighty" who requires immediate resuscitation?

I had some kind of vague idea of language, by the way, you noticed this very accurately. But most likely it was an association with the Babylonian division of languages. The American and Abbot Erm would not have been able to understand each other, even if they had not spoken through an interpreter... And at the same time, the trick with the “fake Chinese” is that they are just real, and it’s all about the idea of them and their "mauvais" of a monk-gardener. As for the “Lavrishchevites”, the creation of their own “elite”, but in fact flat and colorless language is their deliberate desire to draw a line between themselves and the “incomplete members”.

Quote from your novel, chapter “Female Priesthood”: “...Never think that you can make humanity happy with your poems! Never try to predict how they might evaluate what you write! Listen to everyone who will express their opinion about your opuses, but don’t listen! - This is how the famous writer Strelbitsky instructed me and, of course, it was not for me to convert him to my faith...” Do you listen to reviews about your novel and do you listen?

Of course, I listen and read with great attention. Unfortunately, now criticism is reduced to a brief retelling of the content, unraveling prototypes and polemics around the ideas of the novel. It would be much more interesting for me to read an intelligent analytical article, even a very harsh and abusive one, than the reproaches of some home-grown critic that, say, I do not like Catholics. But why don't I like them? I even love them very much in France, especially in the United States. I love them in Africa, in Asia. I love them in Mexico, where they were persecuted during the Mexican Revolution, when monks were expelled from monasteries, churches were emptied... In general, I am not interested in reading ideological criticism, although it is funny.

Your creativity is multifaceted and you don’t even know how to recommend you “in one word” - as a poet, prose writer, publicist... How do you see yourself?

I am a man of sensation and intuition, not analysis and discourse. For me, a visual or musical image is important - an event, a person, a particular time and space. Style is important to me. That is, something that, although it can be to some extent rationally decomposable and explained, can exist without any analysis or justification. I was very happy when I read in the notes of Archpriest Alexander Elchaninov that we perceive some things primarily stylistically. This confirmed the validity of my worldview. Therefore, I believe that I am first and foremost a poet.

Besides, when I write poetry, I feel as if this is my home, I am the mistress here, I do what I want, I am my own mistress, and no one can tell me. An amazing feeling of freedom: complete autocracy. With prose, of course, everything is different. In these spaces, I feel like a wanderer, a traveler, who is interested in everything, everything is new, everything is a holiday, but it is still unknown where he will lay his head, where he can get food, where he will be received with open arms, and where he will be kicked and slapped slap on the wrist: this is the land that still needs to be properly known, studied and made yours. Well, journalism is just that: putting things in order in thoughts and feelings.

What do you think is the meaning of creativity? Could you write on a table, or does a real artist need a reader?

Creativity is the calling of every person. As for me, for me literary creativity is a way of life. I think if I found myself on a desert island and there was a pen and paper there, I would sit on a big rock and write all sorts of poems, stories, novels.

Another quote from the novel: “Love has grown cold ‹…›. You see, it has cooled, it’s already completely cold, it’s almost gone... No, I’m not saying - there, .. with Christ. But on earth, here, between all of us - it’s almost gone. ‹…› But man longs for it. He wants to be loved, in spite of everything! Because that’s exactly how he was conceived, that’s exactly how God sees him. And when he’s loved, he’s exactly that!” Today is precisely the era of “cooling love.” Has love ever been hot and will it ever be again? And what does a person need to do for this?

The Gospel says everything about this: “And because iniquity increases, the love of many will grow cold” (Matthew 24:12). A person who loves God and strives to be with Him cannot help but love people. On the other hand, your love must be nurtured and cherished, and preserved, and preserved. However, everything good must also be preserved (intelligence, talent, kindness). My mother once told me: “If you really love someone, then hold this love of yours with both hands, with all your fingers, don’t let go, so that it doesn’t leave you.” And it’s amazing: I can no longer stop loving all the people whom I have fallen in love with over my long life, even if I no longer have any relationships with these people or I haven’t seen or dated them for a long time. To stop loving someone is a terrible shock to the soul, a big disaster.

Photo by Dmitry Borovsky

V, 25-28), during the feast of the king of Babylon Belshazzar and his desecration of the sacred vessels brought from the Jerusalem temple, a human hand appeared, which inscribed some words on the wall with a finger. When none of the Babylonian wise men could explain or even read what was written, the prophet Daniel was called; according to his explanation, these words meant: God has numbered your kingdom (mene), you are weighed on the scales (fekel), i.e. it turned out that you lack something for which your existence could be extended, and your kingdom is divided (fares ). According to generally accepted opinion, the last word refers to the Persians.

Encyclopedic Dictionary F.A. Brockhaus and I.A. Efron. - S.-Pb.: Brockhaus-Efron. 1890-1907 .

See what “Mene mene tekel fares” is in other dictionaries:

- (Meneh, meneh, tekel, upharsin). According to the biblical story (Dan., V, 25-28), during the feast of the Babylonian king Belshazzar and his mockery of the sacred vessels brought from the Jerusalem temple, a human hand appeared, which... ... Encyclopedic Dictionary F.A. Brockhaus and I.A. Ephron

Rembrandt's painting depicting Belshazzar's feast Mene, mene, tekel, upharsin (Hebrew: מְנֵא מְנֵא תְּקֵל וּפַרְסִין, in Aramaic means letters ... Wikipedia

Mene, tekel, upharsin or mene, tekel, fares- an inscription on the wall of the palace that appeared during a feast and was interpreted as predicting the fall of the kingdom (Tanakh, Daniel 5:25, Christians have the Old Testament, Daniel 5:25): ஐ I tapped it with my finger, and immediately at the point of contact it grew small… … Lem's World - Dictionary and Guide

Mene Tekel Fares- (weighed, counted, divided) mysterious words, according to biblical legend, inscribed by an invisible hand on the wall during a feast at the Babylonian king Belshazzar, prophesying his death. Used to express an omen of death ... Popular Political Dictionary

Mene, mene, tekel, upharsin Rembrandt's painting of Belshazzar's feast Mene, mene, tekel, upharsin (Hebrew: מְנֵא מְנֵא תְּקֵל וּפַרְסִין, in Aramaic literally means “mina, mina, shekel and half a mina" (these are measures of weight), in Church Slavonic ... Wikipedia

- “Expulsion of traders from the temple.” Nikolai Haberschrak, mid-15th century Biblical monetary units of the Middle East, ancient Greek, ancient Roman and others ... Wikipedia

Mikhail Weller wrote 9 novels and several dozen short stories. Books by Mikhail Weller Stories and novels Story technology · Rendezvous with a celebrity · The Adventures of Major Zvyagin · Samovar · All about life · Messenger from Pisa · Cassandra · ... Wikipedia

Mikhail Weller wrote 9 novels and several dozen short stories. Books by Mikhail Weller Stories and novels Story technology · Rendezvous with a celebrity · The Adventures of Major Zvyagin · Samovar · All about life · Messenger from Pisa · Cassandra · ... Wikipedia

Mikhail Weller wrote 9 novels and several dozen short stories. Books by Mikhail Weller Stories and novels Story technology · Rendezvous with a celebrity · The Adventures of Major Zvyagin · Samovar · All about life · Messenger from Pisa · Cassandra · ... Wikipedia

Books

- Heavenly fire and other stories, Olesya Nikolaeva. Olesya Nikolaeva is a famous Russian poetess, prose writer, essayist, member of the Writers’ Union, teacher of a creative poetry seminar at the Literary Institute, presenter of the “Fundamentals…