The dispute between two spiritual movements - the “Josephites” and the “non-possessors” at the turn of the 15th - 16th centuries is the apogee of intra-church contradictions of that period, which coincided with a number of vitally important events in the history of our Fatherland. At the same time, many aspects of the spiritual quest of those years remain relevant, since, on the one hand, they left a deep mark on our mentality, and on the other, the Russian Orthodox Church is still guided by them in its daily life.

First of all, it is necessary to characterize the historical situation in the Russian land at this stage, since the Church has never separated itself from the destinies of the country. Moreover, it was with the blessing and with the direct participation of Church leaders that many of the main events took place.

The 15th century was in many ways a landmark for the Moscow state. First of all, these are the foreign policy successes of Rus', revived after the Mongol-Tatar devastation. A century has passed since the bloody battle on the Kulikovo field, and the Grand Duke of Moscow Ivan III in 1480 managed to bring to its logical conclusion what Dmitry Donskoy began - to finally legally consolidate complete independence from the Golden Horde, which was inevitably disintegrating into a number of khanates. “The people were having fun; and the Metropolitan established a special annual feast of the Mother of God and a religious procession on June 23 in memory of the liberation of Russia from the yoke of the Mongols: for here is the end of our slavery.”

At the same time as achieving this goal, Moscow succeeded in the historical mission of gathering Russian lands into a single centralized state, surpassing its competitors in the process. Despite the fact that in the second quarter of the 15th century North-Eastern Rus' was struck by a brutal internecine feudal war, the Moscow princes managed to subjugate Tver, Novgorod and a number of other appanage territories to their influence, and also recapture a vast part of the western Russian lands from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

In addition, another event occurred on the world stage that greatly influenced the worldview of the Russian people, the spiritual and political situation in Rus'. In 1453, the Byzantine Empire fell under the blows of the Ottoman Turks, or rather the fragment that remained of it in the form of Constantinople and its suburbs. Muscovite Rus' remained virtually the only independent Orthodox state in the world, feeling like an island in an alien sea. Together with the Byzantine princess Sophia Palaeologus and the double-headed eagle, as a state emblem, the idea of the succession of power of the Russian prince from the Emperor of Constantinople and of Moscow, as the last and true custodian of the Orthodox faith, gradually penetrated into the consciousness of its society.

This idea was formulated in Church circles. Monk Philotheus was not the first to express it, but in his messages to Vasily III and Ivan IV it sounded most loudly and confidently: “The now united Catholic Apostolic Church of the East shines brighter than the sun throughout the sky, and there is only one Orthodox and great Russian Tsar in all in heaven, like Noah in the ark, saved from the flood, governs and directs the Church of Christ and affirms the Orthodox faith.” The concept of “Moscow - the third Rome” for a long time determined the spiritual priorities of Russia in the world, and during that period it strengthened the foreign policy position of our country in Europe and the East. Even in official titles in relation to the great princes, the Byzantine term “tsar,” i.e., emperor, began to be increasingly used, although the Russian monarchs did not adopt all the traditions of Byzantium, but mainly only the Christian faith and the institution of the Orthodox Church. Thus, the idea of Byzantine universality became isolated within “all Rus'”, and many elements of ancient Greek philosophy, language and Roman antiquity were completely rejected.

The religious situation in North-Eastern Rus' in the 15th - early 16th centuries. remained extremely complex and ambiguous. Several problems made themselves known loudly at once. The attempt of the Patriarchate of Constantinople to attract and prepare the Russian Church for the Ferraro-Florentine Union with Catholics led to the deposition of Metropolitan Isidore of Kiev and All Rus' (Greek by origin) and opened up the possibility for the Russian Church, from 1448, to independently elect metropolitans from among their own compatriots. Fearing the prospects of subordination to the Latin faith, “Moscow became determined to violate the imaginary rights of the Uniate Patriarch over the Russian Church.” De-facto, the Russian Orthodox Church became independent from Constantinople, and the Moscow princes gained even more influence over its politics.

At the same time, ten years later, from 1458, a long period of administrative division of the united Russian Orthodox Church began into the Moscow and Kyiv metropolises, respectively, into the spheres of influence of the Russian state and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (which included the southern and western regions of the former Kievan Rus).

This is how things stood in external church relations. In the 15th century, the Church, with renewed vigor, waged the most decisive struggle against the remnants of ancient Russian paganism, as well as against the influential heresies that appeared in Rus'. Subsequently, the “non-covetous” and “Josephites” will diverge sharply in terms of methods for resolving these issues.

Paganism and its remnants still continued to pose a serious problem for the Church. The influence of pagan remnants on the Russian people at the beginning of the 15th century is evidenced by a document of that period, “The Word of a Certain Lover of Christ...”, which indicates a high level of dual faith, and even inveterate paganism within Rus'. In particular, the unknown author notes the predilection for pagan rituals and superstitions of even educated Christians: “And not only the ignorant do this, but also the enlightened ones - priests and scribes.” In addition, a number of northern Finno-Ugric peoples, included in the orbit of the Russian state, remained in paganism, and in the 14th - 16th centuries there was active missionary activity of the Church to convert them to Christianity.

During the same period of time, dangerous religious doctrines penetrated into Rus', which were, in fact, not just heresies, but sometimes even apostasy. The so-called heresies of Strigolniks and Judaizers acquired especially strong influence. The teaching of the former had its roots in the highly modified Manichaeism of the Bogomils, which came to Rus' from Bulgaria back in the pre-Mongol period, based on ancient Eastern dualism.

Another teaching came to Novgorod from the west in the second half of the 15th century, along with the free-thinking Polish-Lithuanian Jews who found refuge there. Their dogma contained a call to return to the true faith of the times of the Savior, or rather, to the religious experience of the first sects of Judeo-Christians with a large share of the Jewish religion itself, mixed with the rationalistic ideas of the Western forerunners of Protestantism. Since all this was presented from the standpoint of criticism of a fairly large part of the Orthodox clergy, who did not meet the requirements for them and were mired in bribery, drunkenness and debauchery, these heresies found a response in the hearts of not only ordinary people, but even the secular and spiritual aristocracy. Moreover, even Ivan III himself, after the conquest of Novgorod in 1479, “was fascinated by the talents and courtesy of the cunning freethinking archpriests. He decided to transfer them to his capital." For some time, adherents of the sect were able to influence government and government affairs, but soon their activities were outlawed, and Metropolitan Zosima, who provided them with patronage, was removed from power, officially accused of “excessive drinking.”

In such a difficult situation, disputes emerged and began to grow more and more within the Church itself over spiritual and moral guidelines. At the turn of the 15th - 16th centuries, they formed into two groups - the “Josephites” and the “non-covetous”, who did not oppose each other and did not lead to a schism of the Church, but in polemics they looked for ways to further spiritual priorities in the new established reality. The terms “Josephites” and “non-possessors” themselves have a later origin than these events and are associated with the names of two luminaries of Orthodox thought of this period, by whose works the Church largely lives and is guided today - these are the Venerable Joseph of Volotsky and Nil of Sorsky, surrounded by their outstanding followers.

What is the essence of the disagreement between them? There were many controversial issues, but the central questions remained about church land ownership and the structure of monastic life. Historian N. M. Nikolsky wrote in the late 1920s. in Soviet Russia there is a very critical work on the history of the Church (in the spirit of the times, as they say), but even with it one cannot but agree that the Church in this period was a very large landowner. For example, as the same M.N. Nikolsky reports, Ivan III, weakening the Novgorod freemen, subjected local church lands to secularization, taking away from the Church 10 lordly volosts and 3 out of 6 monastic landholdings only in 1478. Enormous wealth often led to great temptations for the unjust distribution of income from land and the personal enrichment of church leaders, which negatively affected the entire authority of the Church. As a result, the question of the need for land ownership and enrichment of the Church (especially monasteries) in general arose within the Church.

On this occasion, the “non-possessors”, led by Rev. Nil Sorsky (who also received the name “Trans-Volga elders”), who inherited the Byzantine tradition of hesychasm, had a strict opinion about the absence of any property not only from an individual monk, but also from the monastery as a whole. The idea of Christ-loving poverty forbade the members of the monasteries “to be the owners of villages and hamlets, to collect taxes and to conduct trade,” otherwise, a different way of life did not correspond to the gospel values. The Church itself was seen by the “non-covetous” as the spiritual shepherd of society with the right of independent opinion and criticism of princely policies, and for this it was necessary to depend as little as possible on the rich grants of secular power. The “non-possessors” saw the understanding of monastic life in ascetic silence, avoidance of worldly concerns and in the spiritual self-improvement of monks.

The Josephites looked at the problem of monastic land ownership somewhat differently. Having an extremely negative attitude towards personal enrichment, they supported the wealth of monasteries as a source of social charity and Orthodox education. The monasteries of the comrades-in-arms of St. Joseph spent enormous, at that time, funds on supporting the needy. The Assumption Volotsk Monastery alone, founded by him, annually spent up to 150 rubles on charity (a cow then cost 50 kopecks); over 7 thousand residents of surrounding villages received financial support; the monastery fed about 700 beggars and cripples, and the shelter housed up to 50 orphans. Such large expenses required a lot of money, which the Church, while maintaining its independence, could receive independently, without princely alms.

In relation to heretics, Joseph Volotsky was more severe than the “non-acquisitive” ones, who had the opinion that heretics should be discussed and re-educated. Nilus of Sorsky spoke out in favor of abandoning repression against heretics, and those who repented of errors should not have been subject to punishment at all, since only God has the right to judge people. In contrast to this point of view, relying on Russian and Byzantine sources of church law, Joseph decisively declares: “Where are they who say that neither a heretic nor an apostate can be condemned? After all, it is obvious that one should not only condemn, but brutally execute, and not only heretics and apostates: those who know about heretics and apostates and did not report to the judges, even if they themselves turn out to be true believers, will accept the death penalty.” Such harsh statements by the monk and the obvious sympathies of the “Josephites” for the Catholic Inquisition in the 19th century gave reason to some liberals to reduce the role of Joseph only to the inspirer of future repressions of Ivan the Terrible. However, the inconsistency of such a judgment was proven not only by church historians, but even by researchers of the Soviet period. Vadim Kozhinov calls this “pure falsification,” citing, for example, the fact that “the main denouncer of the atrocities of Ivan IV, Metropolitan of All Rus', St. Philip, was a faithful follower of St. Joseph.” In heresies, Joseph saw not only a threat to the Orthodox faith, but also to the state, which followed from the Byzantine tradition of “symphony,” i.e., parity of cooperation between secular and church authorities as two forces of one body. He was not afraid to speak out against heretics as ordinary criminals, even when they were favored by Ivan III and some erring church hierarchs.

The differences of opinion between the “non-possessors” and the “Josephites” on the issue of the role and responsibilities of the Orthodox monarch are of no small importance. The “non-covetous” saw the monarch as fair, taming his passions (anger, carnal lusts, etc.) and surrounding himself with good advisers. All this closely resonates with the concept of the “Trans-Volga elders” about personal spiritual growth. “According to Joseph of Volotsky, the main duty of the king, as God’s vicegerent on earth, is to care for the welfare of the flock of Christ,” the extensive powers of the head of state echo no lesser responsibilities to the Church. The sovereign was compared to God in his earthly life, since he had supreme power over people. Joseph Volotsky proposes to correlate the personality of the monarch with Divine laws, as the only criterion “allowing one to distinguish a legitimate king from a tyrant,” which essentially implies in a certain situation the disobedience of subjects to their sovereign, who does not correspond to such qualities.

It is clear that for such reasons, Ivan III, who needed lands for the serving nobility, initially sympathized with the “non-covetous people.” However, as the heresy of the Judaizers was exposed, he began to listen to the authority of the Monk Joseph, although the Grand Duke expressed his desire to seize church lands until his death. This desire was facilitated by the elimination or obsolescence of previously interfering external factors - “the dependence of the Russian Metropolis on the Patriarchate of Constantinople, the close alliance of metropolitans with the Moscow princes, the Horde policy of granting Tarkhanov to the possessions of the Church, and finally, the constant support of church institutions, which the Grand Duke enjoyed in the fight against appanages.” . In the end, the debate between the two spiritual movements, expressed in numerous letters and messages from opponents, found its way out at the church council of 1503.

The decisions of the council summed up, in a way, the first result of the dispute between two intra-church movements. Supporters of Nil Sorsky and Joseph Volotsky (they themselves were also present at the council) mutually condemned the heresy of the Judaizers and other apostasy from the Orthodox faith. At the same time, the “non-possessors” opposed the persecution of heretics, but their position was in the minority. As for church land ownership, the “Josephites” managed to defend it, motivating their right with the “Gift of Constantine” and other legal acts of Orthodox (and not only) monarchs, confirming the donations and inviolability of church lands from the time of the Byzantine emperor Constantine the Great (IV century AD .). Ivan III, who actively took part in the work of the council, tried to secularize the lands of the Church in exchange for monetary compensation and bread allowance (which would have led the Church to a decline in authority and would have made it highly dependent on the princely power), but a serious illness that suddenly struck him stopped this. an event that seemed quite real.

Thus, the “Josephites” won the struggle for inalienable church property, and the grand ducal government had to look for new ways of coexistence with the Church in the next twenty years. Meanwhile, the spiritual image of the monk and his personal non-covetousness, as well as many elements of the monastic community modeled on the Nile of Sorsky, were finally established by the council in monastic life.

The dispute between the “non-possessors” and the “Josephites” continued after the council and the death of Saints Nile and Joseph. Gradually, the “Josephites” gained the upper hand, especially after 1522, when their representatives began to invariably occupy the metropolitan throne. Oppression began against some prominent “non-possessors”, as a result of which the “peaceful” stage of disputes ended and by the middle of the 16th century, many of the monasteries of the “Trans-Volga elders” were empty. And yet this cannot be called a confrontation, since the dispute itself had the character of true Christian humility. Thus, A.V. Kartashev emphasizes that “the quiet, silent victory of the Josephites” is very significant. The quiet, passive retreat of “non-acquisitiveness” is also indicative.” In Western Europe, for example, a somewhat similar spiritual dispute resulted in the Reformation with its 150 years of bloody religious wars.

The “Josephites” who prevailed, without rejecting the best from non-covetousness, established the Church as an independent institution, independent of secular power, but at the same time outlined close cooperation with the state, bringing closer the subsequent “symphony” in their relations. At the same time, from a historical perspective, the constant strengthening of the absolute power of the monarchy led to its desire to subordinate the critical voice of the Church to its interests, which was realized in the 18th century by Peter I.

S: What is the meaning of M. Luther’s idea of “omniholiness”?

-: in comparison with God, absolutely all mortals are insignificant

-: every believer justifies himself before God personally, becoming his own priest and, as a result, no longer needs the services of the clergy

-: reliance only on the state, institutions of secular power

-: only that monarch should rule for whom power is not a privilege, but a burden placed on him by God

-: M. Luther

-: N. Machiavelli

-: J. Calvin

-: J. Buchanan

S: What term was introduced into political and legal use by the monarchomachs - writers who defended the interests of the noble-opposition circles?

-: “sovereignty of the people”, “social contract”

-: “legitimacy of state power”

-: “the right to resist”

- : “sovereignty of the nation”

-: J. Bodin

-: A. Derbe

-: F. Brander

S: According to J. Bodin, the most natural form of the state is:

-: republic

-: federation

-: monarchy

-: confederation

-: T. Campanella

-: N. Machiavelli

S: T. Campanella in his essay “City of the Sun” comes to the conclusion that the cause of all evil in society is:

-: civic selfishness

-: spiritual nihilism

-: private property

-: freethinking

-: democracy

-: anarchism

-: liberalism

-: dictatorship

S: In the history of political and legal thought, a significant mark was left by the following work of B. Spinoza:

-: “Theological-political treatise”

-: “Ethics”

-: “Political treatise”

- : "Policy"

S: According to the position of B. Spinoza, only those states that are built on:

-: Republican-Democratic

-: socialist

-: communist

-: monarchical mode

S: A significant step forward in the science of state and law was the methodology of political and legal phenomena developed by B. Spinoza. Treating the state and law as a system of natural forces that organically extends into the more general mechanism of the universe, he applied:

-: sociological

-: naturalistic

-: psychological

-: philosophical approach

S: During the period of the English bourgeois revolution of the 17th century. The theory of the patriarchal origin of the state was outlined by R. Filmer in the essay “Patriarchy, or the natural power of the king.” He proves that the power of the English kings originates directly from:

-: Richard the Lionheart

-: Roman emperors

-: the progenitor of the human race - Adam

-: Plantagenet

-: monarchical absolutism

-: socialist utopianism

-: early bourgeois liberalism

-: great power chauvinism

V3: Political and legal teachings of Russia during the formation of a single sovereign state, the formation of an estate-representative and absolute monarchy (second half of the 14th – 17th centuries)

-: Spiridon-Sava

-: Apolinarius

-: Filofey

-: Alexy

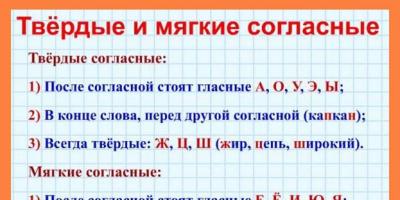

S: How do you understand the idea of secularization of monastic lands in Rus' in the 16th century?

-: distribution of state lands to church ministers

-: transfer of monastic lands into the hands of the state

-: expansion of monastic lands due to the “advancement” of Rus' to the East

-: development of agriculture in territories belonging to monasteries

S: Who are they Josephites?

-: supporters of preserving the church of all its land holdings

-: supporters of obtaining new “worldly benefits” ??????

-: adherents of wars of conquest with neighboring states

-: champions of non-covetousness, the ascetic lifestyle of the clergy

S: Who was the ideological inspirer of the Josephites?

-: N. Sorsky

-: I. Volotsky

-: V. Patrikeev

-: S. Helmsman

S: To A.M. Kurbsky dedicated “The Story of the Grand Duke of Moscow”?

-: Vasily III

-: Ivan III

-: Ivan IV

S: In “The Tale of Tsar Constantine” I.S. Peresvetov proves that the main reason for the capture of Constantinople by the Turks was:

-: the weakness of the Byzantine emperor: “But it is impossible for the king to be without a threat; like a horse under a king without a bridle...”

-: Betrayal of Orthodoxy by Byzantium

-: the dominance of the Byzantine nobles, who “exhausted” the state, robbed its treasury, took “promises…. from legal and guilty"

-: the invincibility of a strong and disciplined Turkish army

S: How did radicalism manifest itself in the views of the heretic F. Kosy?

-: denial of the official church, monasticism, monasteries

-: opposition to monastic and church land ownership???????

-: a call to disobey the church and authorities

- : denial of God

The heresy of Theodosius Oblique is the most radical of all heretical movements of Ancient Rus'. Heretics denied Holy Tradition, the need for the Church and church land ownership, Orthodox prayers and sacraments. They also denied the worship of the cross, because the cross is only a tree.

S: Find the false proposition. The peasants' dissatisfaction with the existing system resulted in a peasant war under the leadership of I.I. Bolotnikov (1606-1607). Moving towards Moscow, Bolotnikov sent out “sheets” that outlined the main goals of the uprising:

-: deal with feudal lords and rich townspeople

-: a complete renewal of the state apparatus was planned

-: establishment of republican rule

-: overthrow the king and replace him with the “legitimate king”

S: The direction of social thought in the 16th century. called "humanism". Choose a historical synonym for this word.

-: anti-reformation

-: existentialism

-: ideology of the Renaissance

-: anticlericalism

One of the first major intra-church ideological conflicts of Muscovite Rus' was the famous dispute between the Josephites and the Trans-Volga elders (non-possessors) (see also in the article Nil Sorsky and Joseph Volotsky). Here, in essence, two understandings of Orthodoxy collided in its relation to the “world.” Although this conflict also did not receive a principled formulation into force, it was precisely a matter of principles. A dispute between the Josephites and the Trans-Volga elders arose over two specific issues: over the fate of the monastic property and over the issue of methods of combating the “heresy of the Judaizers” that had then appeared in Novgorod. But in relation to these two issues, the difference between the social and ethical worldview of both movements clearly emerged.

First we need to say a few words about the historical background of the dispute. From the very beginning of Christianity in Rus', monasteries were hotbeds of Christian enlightenment and played a decisive role in the Christianization of morals. However, over time, when the monasteries turned out to be the owners of vast lands and all kinds of wealth, life in the monastery became a temptation for all sorts of parasites who went there not so much for the salvation of their souls, but for a comfortable and safe life. Monastic morals, which had been strict before, were significantly weakened. But, in addition, a movement arose in the monasteries themselves, led by Nil Sorsky, who believed that monasteries should be, first of all, a focus of asceticism and prayer, that monks should be “non-acquisitive” - not have any property and eat only from the fruits of their own labor. The energetic and powerful Joseph Volotsky, abbot of the Volokolamsk monastery, spoke out against him. Joseph was also aware that there was a decline in morals in the monasteries, but he proposed to combat this evil by introducing strict discipline. He considered the very concentration of wealth in monasteries useful for strengthening the authority and power of the church. Speaking in defense of the monastic property, Joseph was at the same time a prominent apologist for the authority of the royal power. He seemed to offer the state a very close alliance with the church, in every possible way supporting the princes of Moscow in their unification policy. Therefore, at the convened Church Council, the Grand Duke of Moscow ultimately supported the Josephites, who emerged victorious in disputes with the “Volga residents.”

Joseph Volotsky

The victory of the Josephites corresponded to the then trends in the general development of Rus' towards strengthening unity at the expense, perhaps, of spiritual freedom (XV - XV centuries). The ideal of the Volga residents, who called for non-covetousness, for spiritual rebirth (“smart prayer”), for going to a monastery, was too impractical for that harsh time. It should be noted that Nil Sorsky, one of the most enlightened Russian saints, also spoke out against the excesses of external asceticism (asceticism, mortification, etc.). Above all, he placed “smart prayer”, purity of mental state and active help to others. His students even spoke out in the spirit that it was better to help people than to spend money on decorating temples too splendidly. It was not for nothing that he spent many years on Athos, which was experiencing its revival, where the influence of the great ascetic and father of the church, St. Gregory Palamas. In contrast, Joseph primarily emphasized the strictness of the monastic rules, the purity of ritual and church “splendor.” If Nile appealed to the highest strings of the soul - to inner freedom, to purity of spiritual orientation, then Joseph, as a strict teacher and organizer, had in mind primarily ordinary monks, for whom discipline and, in general, strict adherence to the rules should have the main educational significance. Joseph acted with severity, St. Neil - with kindness.

In Russian historiography, the sympathies of historians invariably fell on the side of the Nile, and many consider the very figure of Joseph fatal for the fate of the church in Russia. Nil of Sorsky became the favorite saint of the Russian intelligentsia. This assessment, both from our modern point of view and in general, is correct. However, historically it needs reservations: from a historical point of view, it is impossible to portray Neil as an “advanced, enlightened shepherd”, and Joseph as only a “reactionary”. Neil advocated for “old times” - for the restoration of the former moral and mystical heights of the monasteries. Joseph, for that time, was a kind of “innovator”; he emphasized, speaking in modern language and in relation to the conditions of that time, the socio-political mission of Orthodoxy, which he saw in the correction of morals through the rigor and sincerity of the ritual and charter and in the closest cooperation with the grand ducal authority. The ideals of the Nile were actually put into practice at the dawn of Christianity in Rus', when the church was not so closely connected with the political life of the country and was more concerned about the moral education of the people.

Neil Sorsky

The difference between both camps was even more pronounced in their attitude towards the heresy of the Judaizers. The founder of the heresy was the learned Jew Skhariya, and it spread mainly in Novgorod. “Judaizers” gave the Bible priority over the New Testament, they denied the sacraments and doubted the dogma of the Holy Trinity. In a word, it was a rationalistic, as it were, Protestant sect. It is no coincidence that this heresy spread precisely in Novgorod, which always maintained close relations with the West, but its worldview was really close to Judaism. At one time, the “Judaizers” were successful - the Metropolitan of Novgorod himself was close to her, and at one time even Grand Duke Ivan III was inclined towards this heresy. But thanks to the accusatory sermons of the new Novgorod Archbishop Gennady and then Joseph of Volokolamsk himself, this heresy was exposed and suppressed.

However, the disciples of Nil Sora at the Church Council proposed to fight the new heresy with word and conviction, while Joseph was a supporter of the direct persecution of heretics. And in this matter the Josephites prevailed, and some of the Volga residents (in particular, the “prince-monk” Vassian Patrikeev) subsequently paid with their lives.

We briefly recalled the history of this dispute. But what is most important to us is its meaning. Some historians, for example father Georgy Florovsky, consider the victory of the Josephites to be essentially a break with Byzantium in favor of the Muscovite-Russian principle. They refer to the fact that the movement of the Trans-Volga elders arose due to the influence of the Greek " hesychasts"- teachings about the need for moral cleansing and removal from worldly vanity that came with Athos Monastery. This teaching was also associated with the so-called Light of Tabor, foreshadowing the imminent end of the world. However, the tendency of Joseph Volotsky has its parallels in Byzantium. Emphasizing the strictness of the charter and ritual, close cooperation between the church and the state - after all, this is also a Byzantine tradition. Essentially, the dispute between the Josephites and the Volga elders was a dispute between two Byzantine traditions, which were already quite firmly transplanted onto Russian soil. But in any case, the victory of strictly “everyday confessionalism” over the mystical, grace-filled stream contributed to the further nationalization of the Russian Church and separation from the tradition of universal Christianity. The victory of the Josephites was a prerequisite for the later schism, based on the opposition of “Russian” Orthodoxy to “Greek” Orthodoxy. It also contributed to further theological lethargy, for, although Nilus of Sora cannot be considered a Christian thinker, he is only a more free-thinking reader than Joseph, but his tradition, which gave great scope to the mind, could create the preconditions for an earlier awakening of religious and philosophical thought in us .

Speaking about the “Volga region people,” one cannot ignore Maxim the Greek, who was invited by Ivan III to translate the Greek originals. This remarkable scientist, a Greek from Italy, could, according to the reviews of his contemporaries, become the pride of Greek-Italian science; however, he preferred to accept the invitation of the Grand Duke and go to Muscovy, where his fate was sad. Exiled for many years to remote places, he died prematurely. Charges of a political nature were brought against him, which may have been justified. But it is characteristic that he supported the “Volga residents” with his authority and even managed to create a small circle of “Christian humanists” around himself.

The only more or less independent Russian theological writer of the 16th century came out of the school of Maxim the Greek - Zinovy Otensky, author of the work “Truth, testimony to those who asked about the new teaching.” He moves entirely in the traditions of Greek patristics, and it is difficult to call him more than a knowledgeable compiler, but still it was the fruit of the rudiments of Russian theology worthy of the attention of a historian. Unfortunately, he was subjected to repression, and this tradition was not continued. From this circle later came such an outstanding figure as the first Russian emigrant, Prince Kurbsky. In the well-known correspondence between Kurbsky and Ivan the Terrible, the prince, among other things, accused Ivan of having “closed the Russian land, that is, free human nature, like a stronghold in hell.” This emphasis on “natural law” (“free human nature”) undoubtedly comes from Italy and, through Maxim the Greek, somehow resonates with the more humanistic direction of the “Volga residents.” Ivan, in his “long-winded” writings, especially emphasized the divine origin of royal power and his right to “execute and pardon” at his own discretion. He will give an answer only before God's court.

However, it should be noted that the famous Council of the Hundred Heads, convened under Ivan the Terrible, was organized on the initiative of Macarius and Sylvester, students of Joseph of Volokolamsk. Macarius, chief compiler Chet'i-Minei", this encyclopedia of ancient Russian church education, was an enlightened Josephite. It is known that he had a good influence on young John. This already indicates that the Josephites, having defeated the Trans-Volga people, in the second generation did not become “reactionaries”, but to some extent adopted the Trans-Volga spirit of tolerance and humanity.

Since the time of two spiritual movements - the “Josephites” and the “non-possessors” at the turn of the 15th-16th centuries, it has been the apogee of intra-church contradictions of this period, which coincided with a number of vitally important events in the history of our Fatherland. At the same time, many aspects of the spiritual quest of those years remain relevant, since, on the one hand, they left a deep mark on our mentality, and on the other, the Russian Orthodox Church is still guided by them in its daily life.

First of all, it is necessary to characterize the historical situation in the Russian land at this stage, since the Church has never separated itself from the destinies of the country. Moreover, it was with the blessing and with the direct participation of Church leaders that many of the main events took place.

The 15th century was in many ways a landmark for the Moscow state. First of all, these are the foreign policy successes of Rus', revived after the Mongol-Tatar devastation. A century has passed since the bloody battle on the Kulikovo field, and the Grand Duke of Moscow Ivan III in 1480 managed to bring to its logical conclusion what Dmitry Donskoy began - to finally legally consolidate complete independence from the Golden Horde, which was inevitably disintegrating into a number of khanates. “The people were having fun; and the Metropolitan instituted a special annual feast of Our Lady and a religious procession on June 23 in memory of the liberation of Russia from the yoke of the Mongols: for here is the end of our slavery.”

At the same time as achieving this goal, Moscow succeeded in the historical mission of gathering Russian lands into a single centralized state, surpassing its competitors in the process. Despite the fact that in the second quarter of the 15th century North-Eastern Rus' was struck by a brutal internecine feudal war, the Moscow princes managed to subjugate Tver, Novgorod and a number of other appanage territories to their influence, and also recapture a vast part of the western Russian lands from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

In addition, another event occurred on the world stage that greatly influenced the worldview of the Russian people, the spiritual and political situation in Rus'. In 1453, the Byzantine Empire fell under the blows of the Ottoman Turks, or rather, the fragment that remained of it in the form of Constantinople and its suburbs. Muscovite Rus' remained virtually the only independent Orthodox state in the world, feeling like an island in an alien sea. Together with the Byzantine princess Sophia Palaeologus and the double-headed eagle, as a state emblem, the idea of the succession of power of the Russian prince from the Emperor of Constantinople and of Moscow as the last and true custodian of the Orthodox faith gradually penetrated into the consciousness of its society.

This idea was formulated in Church circles. Monk Philotheus was not the first to express it, but in his messages to Vasily III and Ivan IV it sounded most loudly and confidently: “The now united Catholic Apostolic Church of the East shines brighter than the sun throughout the sky, and there is only one Orthodox and great Russian Tsar in everything in the heavens, like Noah in the ark, who was saved from the flood, governs and directs the Church of Christ and affirms the Orthodox faith.” The concept of “Moscow - the third Rome” for a long time determined the spiritual priorities of Russia in the world, and during that period it strengthened the foreign policy position of our country in Europe and the East. Even in official titles in relation to the great princes, the Byzantine term “tsar,” i.e., emperor, began to be increasingly used, although the Russian monarchs did not adopt all the traditions of Byzantium, but mainly only the Christian faith and the institution of the Orthodox Church. Thus, the idea of Byzantine universality became isolated within “all Rus'”, and many elements of ancient Greek philosophy, language and Roman antiquity were completely rejected.

The religious situation in North-Eastern Rus' in the 15th - early 16th centuries. remained extremely complex and ambiguous. Several problems made themselves known loudly at once. The attempt of the Patriarchate of Constantinople to attract and prepare the Russian Church for the Ferraro-Florentine Union with Catholics led to the deposition of Metropolitan Isidore of Kiev and All Rus' (Greek by origin) and opened up the possibility for the Russian Church, from 1448, to independently elect metropolitans from among their own compatriots. Fearing the prospects of subordination to the Latin faith, “Moscow became determined to violate the imaginary rights of the Uniate Patriarch over the Russian Church.” De facto The Russian Orthodox Church became independent from Constantinople, and the Moscow princes gained even more influence on its politics.

At the same time, ten years later, from 1458, a long period of administrative division of the united Russian Orthodox Church began into the Moscow and Kyiv metropolises, respectively, into the spheres of influence of the Russian state and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (which included the southern and western regions of the former Kievan Rus).

This is how things stood in external church relations. In the 15th century, the Church, with renewed vigor, waged the most decisive struggle against the remnants of ancient Russian paganism, as well as against the influential heresies that appeared in Rus'. Subsequently, the “non-covetous” and “Josephites” will diverge sharply in terms of methods for resolving these issues.

Paganism and its remnants still continued to pose a serious problem for the Church. The influence of pagan remnants on the Russian people at the beginning of the 15th century is evidenced by a document of that period, “The Word of a Certain Lover of Christ...”, which indicates a high level of dual faith, and even inveterate paganism within Rus'. In particular, the unknown author notes the predilection for pagan rituals and superstitions of even educated Christians: “And not only the ignorant do this, but also the enlightened ones - priests and scribes.” In addition, a number of northern Finno-Ugric peoples, included in the orbit of the Russian state, remained in paganism, and in the XIV-XVI centuries there was active missionary activity of the Church to convert them to Christianity.

During the same period of time, dangerous religious doctrines penetrated into Rus', which were, in fact, not just heresies, but sometimes even apostasy. The so-called heresies of Strigolniks and Judaizers acquired especially strong influence. The teaching of the former had its roots in the highly modified Manichaeism of the Bogomils, which came to Rus' from Bulgaria back in the pre-Mongol period, based on ancient Eastern dualism.

Another teaching came to Novgorod from the west in the second half of the 15th century, along with the free-thinking Polish-Lithuanian Jews who found refuge there. Their dogma contained a call to return to the true faith of the times of the Savior, or rather, to the religious experience of the first sects of Judeo-Christians with a large share of the Jewish religion itself, mixed with the rationalistic ideas of the Western forerunners of Protestantism. Since all this was presented from the standpoint of criticism of a fairly large part of the Orthodox clergy, who did not meet the requirements for them and were mired in bribery, drunkenness and debauchery, these heresies found a response in the hearts of not only ordinary people, but even the secular and spiritual aristocracy. Moreover, even Ivan III himself, after the conquest of Novgorod in 1479, “was fascinated by the talents and courtesy of the cunning freethinking archpriests. He decided to transfer them to his capital." For some time, adherents of the sect were able to influence government and government affairs, but soon their activities were outlawed, and Metropolitan Zosima, who provided them with patronage, was removed from power, officially accused of “excessive drinking.”

In such a difficult situation, disputes emerged and began to grow more and more within the Church itself over spiritual and moral guidelines. At the turn of the 15th-16th centuries, they formed into two groups - the “Josephites” and the “non-covetous”, who did not oppose each other and did not lead to a schism of the Church, but through polemics sought ways of further spiritual priorities in the new established reality. The terms “Josephites” and “non-covetous” themselves have a later origin than these events, and are associated with the names of two luminaries of Orthodox thought of this period, by whose works the Church largely lives and is guided today - these are the reverends and, surrounded by their outstanding followers.

What is the essence of the disagreement between them? There were many controversial issues, but the central questions remained about church land ownership and the structure of monastic life. Historian N. M. Nikolsky wrote in the late 1920s. in Soviet Russia there is a very critical work on the history of the Church (in the spirit of the times, as they say), but even with it one cannot but agree that the Church in this period was a very large landowner. For example, as the same M.N. Nikolsky reports, Ivan III, weakening the Novgorod freemen, subjected local church lands to secularization, taking away from the Church 10 lordly volosts and 3 out of 6 monastic landholdings only in 1478. Enormous wealth often led to great temptations for the unjust distribution of income from land and the personal enrichment of church leaders, which negatively affected the entire authority of the Church. As a result, the question of the need for land ownership and enrichment of the Church (especially monasteries) in general arose within the Church.

On this occasion, the “non-possessors”, led by Rev. Nil Sorsky (who also received the name “Trans-Volga elders”), who inherited the Byzantine tradition of hesychasm, had a strict opinion about the absence of any property not only from an individual monk, but also from the monastery as a whole. The idea of Christ-loving poverty forbade the members of the monasteries “to be the owners of villages and hamlets, to collect taxes and to conduct trade,” otherwise, a different way of life did not correspond to the gospel values. The Church itself was seen by the “non-covetous” as the spiritual shepherd of society with the right of independent opinion and criticism of princely policies, and for this it was necessary to depend as little as possible on the rich grants of secular power. The “non-possessors” saw the understanding of monastic life in ascetic silence, avoidance of worldly concerns and in the spiritual self-improvement of monks.

The Josephites looked at the problem of monastic land ownership somewhat differently. Having an extremely negative attitude towards personal enrichment, they supported the wealth of monasteries as a source of social charity and Orthodox education. The monasteries of the comrades-in-arms of St. Joseph spent enormous, at that time, funds on supporting the needy. The Assumption Volotsk Monastery alone, founded by him, annually spent up to 150 rubles on charity (a cow then cost 50 kopecks); over 7 thousand residents of surrounding villages received financial support; the monastery fed about 700 beggars and cripples, and the shelter housed up to 50 orphans. Such large expenses required a lot of money, which the Church, while maintaining its independence, could receive independently, without princely alms.

In relation to heretics, Joseph Volotsky was more severe than the “non-acquisitive” ones, who had the opinion that heretics should be discussed and re-educated. Nilus of Sorsky spoke out in favor of abandoning repression against heretics, and those who repented of errors should not have been subject to punishment at all, since only God has the right to judge people. In contrast to this point of view, relying on Russian and Byzantine sources of church law, Joseph decisively declares: “Where are they who say that neither a heretic nor an apostate can be condemned? After all, it is obvious that it is necessary not only to condemn, but to brutally execute, and not only heretics and apostates: those who know about heretics and apostates and did not report to the judges, even if they themselves turn out to be true believers, will accept the death penalty.” Such harsh statements by the monk and the obvious sympathies of the “Josephites” for the Catholic Inquisition in the 19th century gave reason to some liberals to reduce the role of Joseph only to the inspirer of future repressions of Ivan the Terrible. However, the inconsistency of such a judgment was proven not only by church historians, but even by researchers of the Soviet period. Vadim Kozhinov calls this “pure falsification,” citing, for example, the fact that “the main denouncer of the atrocities of Ivan IV, Metropolitan of All Rus' Saint Philip, was a faithful follower of St. Joseph.” In heresies, Joseph saw not only a threat to the Orthodox faith, but also to the state, which followed from the Byzantine tradition of “symphony,” i.e., parity of cooperation between secular and church authorities as two forces of one body. He was not afraid to speak out against heretics as ordinary criminals, even when they were favored by Ivan III and some erring church hierarchs.

The differences of opinion between the “non-possessors” and the “Josephites” on the issue of the role and responsibilities of the Orthodox monarch are of no small importance. The “non-covetous” saw the monarch as fair, taming his passions (anger, carnal lusts, etc.) and surrounding himself with good advisers. All this closely echoes the concept of the “Trans-Volga elders” about personal spiritual growth. “According to Joseph of Volotsky, the main duty of the king, as God’s vicegerent on earth, is to care for the welfare of the flock of Christ,” the extensive powers of the head of state echo no lesser responsibilities to the Church. The sovereign was compared to God in his earthly life, since he had supreme power over people. Joseph Volotsky proposes to correlate the personality of the monarch with Divine laws, as the only criterion “allowing one to distinguish a legitimate king from a tyrant,” which essentially implies in a certain situation the disobedience of subjects to their sovereign, who does not correspond to such qualities.

It is clear that for such reasons, Ivan III, who needed lands for the serving nobility, initially sympathized with the “non-covetous people.” However, as the heresy of the Judaizers was exposed, he began to listen to the authority of the Monk Joseph, although the Grand Duke expressed his desire to seize church lands until his death. This desire was facilitated by the elimination or obsolescence of previously interfering external factors - “the dependence of the Russian Metropolis on the Patriarchate of Constantinople, the close alliance of metropolitans with the Moscow princes, the Horde policy of granting Tarkhanov to the possessions of the Church, and finally, the constant support of church institutions, which the Grand Duke enjoyed in the fight against appanages.” . In the end, the debate between the two spiritual movements, expressed in numerous letters and messages from opponents, found its way out at the church council of 1503.

The decisions of the council summed up, in a way, the first result of the dispute between two intra-church movements. Supporters of Nil Sorsky and Joseph Volotsky (they themselves were also present at the council) mutually condemned the heresy of the Judaizers and other apostasy from the Orthodox faith. At the same time, the “non-possessors” opposed the persecution of heretics, but their position was in the minority. As for church land ownership, the “Josephites” managed to defend it, motivating their right with the “Gift of Constantine” and other legal acts of Orthodox (and not only) monarchs, confirming the donations and inviolability of church lands from the time of the Byzantine emperor Constantine the Great (IV century AD .). Ivan III, who actively took part in the work of the council, tried to secularize the lands of the Church in exchange for monetary compensation and bread allowance (which would have led the Church to a decline in authority and would have made it highly dependent on the princely power), but a serious illness that suddenly struck him stopped this. an event that seemed quite real.

Thus, the “Josephites” won the struggle for inalienable church property, and the grand ducal government had to look for new ways of coexistence with the Church in the next twenty years. Meanwhile, the spiritual image of the monk and his personal non-covetousness, as well as many elements of the monastic community modeled on the Nile of Sorsky, were finally established by the council in monastic life.

The dispute between the “non-possessors” and the “Josephites” continued after the council and the death of Saints Nile and Joseph. Gradually, the “Josephites” gained the upper hand, especially after 1522, when their representatives began to invariably occupy the metropolitan throne. Oppression began against some prominent “non-possessors”, as a result of which the “peaceful” stage of disputes ended, and by the middle of the 16th century, many of the monasteries of the “Trans-Volga elders” were empty. And yet this cannot be called a confrontation, since the dispute itself had the character of true Christian humility. Thus, A.V. Kartashev emphasizes that “the quiet, silent victory of the Josephites is very significant. The quiet, passive retreat of “non-covetousness” is also indicative.” In Western Europe, for example, a somewhat similar spiritual dispute resulted in the Reformation with its 150 years of bloody religious wars.

The “Josephites” who gained the upper hand, without rejecting the best from non-covetousness, established the Church as an independent institution, independent of secular power, but at the same time outlined close cooperation with the state, bringing closer the subsequent “symphony” in their relations. At the same time, from a historical perspective, the constant strengthening of the absolute power of the monarchy led to its desire to subordinate the critical voice of the Church to its interests, which was realized in the 18th century by Peter I.

JOSEPHLANES, supporters of a special direction of Russian social thought (late 15-16 centuries), named after its main inspirer - Joseph of Volotsky. The term “Josephites” was used by Prince A.M. Kurbsky; it appeared in scientific literature in the 2nd half of the 19th century.

Initially, the Josephites supported the idea of the dominance of spiritual power over secular power. The ruler, according to Joseph Volotsky, is an earthly man and a simple executor of God’s will, therefore he should be given “royal honor, not divine honor.” If a tyrant was established on the throne, then he should not have been obeyed, for he was “not God’s servant, but the devil, and not a king, but a tormentor.” The rapprochement of Joseph of Volotsky with the Grand Duke of Moscow Ivan III Vasilyevich led to a change in the views of the Josephites on the nature of the grand-ducal power. Recognizing its divine character, Joseph Volotsky declared the need to submit to the ruler all institutions of the state and the Church, while the “priesthood” was given a high mission - to fulfill the role of the spiritual mentor of the sovereign.

In the church polemics at the turn of the 15th-16th centuries about monastic land ownership, which developed against the backdrop of the decline of the internal discipline of cenobitic monasteries, the Josephites, in contrast to their ideological opponents - non-acquisitive people (see also Nil Sorsky), supporters of the hermitage form of monasticism, advocated the preservation of monasteries and their renovation internal life on the basis of the mandatory introduction of strict communal regulations. The establishment of a strict community life, according to the Josephites, made it possible to combine the growth of monastic possessions with the principles of personal monastic non-covetousness and renunciation of the world. The position of the Josephites on the issue of monastic land ownership prevailed at the council of 1503, and was later confirmed by the council of 1531. Josephite monasteries were characterized by attaching special importance to the institution of eldership: each young monk was under the supervision of an experienced monk, which strengthened the spiritual continuity between teacher and student (Joseph Volotsky - Cassian Barefoot - Photius Volotsky - Vassian Koshka). The Josephites were actively involved in monastery construction, erecting and decorating churches, collecting icons and books. Joseph Volotsky invited the best painters to paint the monastery's Assumption Cathedral (see Joseph-Volotsky Monastery) - Dionysius and his sons Theodosius and Vladimir; Icons by Andrei Rublev were kept in the monastery; there was a scriptorium and a literary school. The Josephites opposed the extremes of asceticism and saw the ideal of monasticism not in isolation from the outside world, but in active activity in all spheres of public life. Monasticism, in their opinion, was supposed to influence all state institutions, support grand-ducal power, educate future archpastors, conduct cultural, educational and missionary work, and resist heresies (thus, at the council of 1504, the Josephite position in relation to heretics prevailed - “the army and the knife ", executions and imprisonment).

At the beginning of the 16th century, the Josephites occupied Rostov (Vassian Sanin), Kolomna (Mitrofan), Suzdal (Simeon) and other departments. Under Metropolitan Daniel of Moscow, many hierarchs of the Russian Church adhered to pro-Josephite positions [bishops Akaki of Tver, Vassian of Kolomensky (Toporkov), Savva of Smolensk, Jonah of Ryazan, Macarius of Novgorod]. Metropolitan Daniel, former abbot of the Joseph-Volotsk Monastery, actively supported the policy of unification of Russian lands pursued by the Grand Duke of Moscow Vasily III Ivanovich, justified from the church canonical point of view the divorce of the Grand Duke from S. Yu. Saburova, married him to E. V. Glinskaya. Volotsk monks participated in the baptism of the future Tsar Ivan IV Vasilyevich, supervised the burial of Vasily III Ivanovich, and acted as the main prosecutors in the trials of Maxim the Greek and Vassian (Patrikeev), M. S. Bashkin and Theodosius Kosoy. In the 1540-50s, when Macarius, who was close to the Josephites, became Metropolitan of Moscow, all the most important church posts were occupied by his like-minded people. At the Council of the Stoglavy (1551), the Josephite majority (Archbishop Theodosius of Novgorod, Bishops Savva of Krutitsky, Gury of Smolensk, Tryphon of Suzdal, Akaki of Tver, Nikandr of Rostov, Theodosius of Kolomna, Cyprian of Perm) finally rejected the non-covetous program proposed by A. F. Adashev and Sylvester, and approved the principle of inalienability of church lands. Thanks to the activities of Metropolitan Macarius and his “squad”, the “Great Chetya Menaion” was compiled - a collection of “all the hagiographic and teaching works that were celebrated” in Rus', distributed by day of the year, the canonization of more than 30 Russian saints was carried out (at the councils of 1547-49), the creation of grandiose architectural monuments glorifying the power of the Russian state (for example, St. Basil's Cathedral). The monk of the Pskov Eleazar Monastery Philotheus was close to the Josephites, who formulated and substantiated in his writings the political concept “Moscow is the third Rome.”

In general, the union of the Josephite Church with the state remained until the 2nd half of the 16th century. Later, the practice of large monastic land ownership and the idea of the inalienability of church property came into conflict with the ideology of the emerging autocracy. An echo of the Josephite church-political doctrine in Russian history of the 17th century was the policy of Patriarch Nikon, which led him to conflict with Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich.

Lit.: Budovnits I. U. Russian journalism of the 16th century. M.; L., 1947; Zimin A. A. I. S. Peresvetov and his contemporaries. M., 1958; aka. Large feudal estate and socio-political struggle in Russia (late 15th - 16th centuries). M., 1977; Klibanov A.I. Reformation movements in Russia in the 14th - first half of the 16th centuries. M., 1960; Lurie Y. S. Ideological struggle in Russian journalism at the end of the 15th - beginning of the 16th centuries. M.; L., 1960; Dmitrieva R.P. Volokolamsk chets collections of the 16th century. // Proceedings of the Department of Old Russian Literature. L., 1974. T. 28; Zamaleev A.F. Philosophical thought in medieval Rus' (XI-XVI centuries). L., 1987; Book centers of Ancient Rus': Joseph-Volokolamsk Monastery as a book center. L., 1991; Olshevskaya L. A. History of the creation of the Volokolamsk patericon, description of its editions and lists // Old Russian patericon. M., 1999.

L. A. Olshevskaya, S. N. Travnikov.