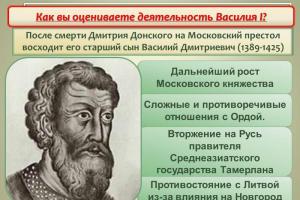

The main activities of Vasily I After the death of Dmitry Donskoy, his eldest son Vasily Dmitrievich ascended to the Moscow throne () Further growth of the Moscow principality Complex and contradictory relations with the Horde. Invasion of Rus' by the ruler of the Central Asian state Tamerlane Confrontation with Lithuania due to influence on Novgorod How do you assess the activities of Vasily I?

Prerequisites for the dynastic war in the second quarter of the 15th century. The struggle of the family and clan order of succession to the princely throne The contradictory text of Dmitry Donskoy’s will, which made it possible to interpret it from different positions Personal rivalry for power in Moscow by the descendants of Prince Dmitry Donskoy What factors led to the fratricidal war in Rus' in the second quarter of the 15th century. ?

Yuri of Galicia and Zvenigorod Vasily I Vasily I died in 1425. For the first time in the history of the Moscow principality, the question arose about who should inherit the deceased: a son or a brother. Yuri Vasily II Previously, the deceased prince always had either a son or a younger brother. In 1389, Dmitry Donskoy bequeathed that Vasily's heir should be his brother Yuri. But in 1415 Vasily had a son, Vasily II. Dmitry Donskoy Vasily I Yuri Galitsky Vasily II Vasily Kosoy Dmitry Shemyaka

Fifty-year-old Yuri Dmitrievich laid claim to the throne. He wanted to return to the previous order of succession by seniority, which would be a departure from inheritance in a direct line from father to son. That was yesterday in history, because the unity of the Russian lands and the power of the Moscow principality were largely ensured precisely by inheritance from father to son and the gradual liquidation of inheritances. Yuri Galitsky and Zvenigorodsky

Andrei Rublev Kirillo-Belozersky Kirill Yuri Dmitrievich was a fine connoisseur of literature and art, patronized the remarkable Russian artist of the turn of the 14th-15th centuries. Andrei Rublev, was in correspondence with the founder of the Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery, Abbot Kirill. Yuri Galitsky and Zvenigorodsky

In Zvenigorod and its surroundings, the prince began the construction of churches and monasteries. In addition, he was a courageous warrior and a successful commander who did not suffer a single defeat on the battlefield. Yuri Galitsky and Zvenigorod Assumption Cathedral “on Gorodok” in Zvenigorod. Nativity Cathedral of the Savvino-Storozhevsky Monastery.

Behind Yuri stood Zvenigorod and Galich, northern Vyatka and Ustyug, the elite of Novgorod sympathized with him. Yuri was also supported by those appanage princelings who dreamed of regaining their former independence. The struggle between adherents of the old, appanage orders and new traditions of succession to the throne in the emerging united Russian state has become a natural phenomenon in history. Yuri Galitsky and Zvenigorodsky

Who supported Vasily II Service princes, boyars, nobles - the basis of the Grand Duke's army Large and small landowners, patrimonial owners and landowners Townspeople, townspeople and merchant people Townspeople, townspeople and trade people Church House of Kalita, relatives of the Grand Duke House of Kalita, relatives of the Grand Duke

Vasily II Immediately after the accession of the young Vasily II to the throne, Yuri Dmitrievich left for Galich and sent letters to all Russian lands calling for disobedience to Vasily II and the gathering of the army. The Moscow army headed to Galich, but Yuri fled from there. A fight began between uncle and nephew, between the forces of centralization of the country and the forces of the appanage freemen. Vasily II

Vasily Yuryevich Kosoy Dmitry Yuryevich Shemyak However, at first it was possible to agree that it was better to resolve the matter peacefully. Vasily II and Yuri went to the Horde for a label for the great reign. They stayed there for a year, and Moscow won the argument. However, Yuri did not agree with this decision and again went to Galich, where everyone dissatisfied with the Moscow government began to flock to his banner. Open confrontation began in 1433 after a quarrel between the sons of Yuri Dmitrievich (Vasily Yuryevich, nicknamed Kosoy and Dmitry Yuryevich, nicknamed Shemyaka) with Vasily II at his wedding. Vasily II

One of the boyars noticed on Vasily Yuryevich a gold-woven belt that once belonged to Dmitry Donskoy and was stolen from the Moscow treasury. The Grand Duke's family took this as a challenge. The mother of Vasily II ordered to immediately remove the belt from Vasily. The insulted sons of Yuri left the feast. Vasily II

A new stage in the struggle for the Moscow throne began. Soon, Yuri Dmitrievich, together with his sons, struck Moscow with a swift and unexpected blow. Defeated on the battlefield and expelled from Moscow, Vasily II immediately became an attractive figure for part of Russian society. Boyars and nobles flocked to Kolomna. Under these conditions, he made an unexpected decision to renounce the Moscow throne and give in to his nephew. Vasily II occupied Moscow and immediately resumed the fight against the rebellious sons of Yuri. And again the Grand Duke was defeated.

Vasily II gathered a new army and moved it into the possessions of Yuri and his sons. And again the Grand Duke lost to his talented uncle. For the second time, Yuri Dmitrievich occupied Moscow, captured the family of the Grand Duke and seized his treasury. Vasily II fled. Yuri ruled for only two months. In 1434 he died. Contrary to all traditions, the eldest son of Yuri Dmitrievich Vasily proclaimed himself Grand Duke. Vasily II

A new stage of the feudal war began. The entire North-Eastern Rus' became the arena of battles and campaigns. Oblique In the decisive battle of 1436, Vasily Yuryevich was defeated by the Moscow army, captured and taken to Moscow. There, by order of the Grand Duke, he was blinded. After this, Vasily Yuryevich acquired the nickname Oblique. 12 years later he died in oblivion. Vasily II

Dmitry Shemyaka The military weakening and ruin of Rus' was immediately taken advantage of by its old enemy, the Horde. The Horde won victories and Vasily II was captured. The Horde demanded a huge ransom for Vasily II. It was collected all over Rus'. It was at this time that the conspiracy organized by Dmitry Shemyaka matured. Rebellion of Dmitry Shemyaka He accused the Grand Duke of inability to protect Rus' from the Horde. On February 12, 1446, the conspirators captured Moscow and sent a detachment to the Trinity-Sergius Monastery, where Vasily the Dark. The prince was there, and he was arrested right in the church. He was brought to Moscow and blinded. In history, Grand Duke Vasily II remained under the name of Vasily the Dark.

In December, Vasily II again captured Moscow and finally took the grand-ducal throne. Vasily II undertook to preserve his inheritance for Shemyaka. In 1449 the war resumed. In 1450 Shemyaka fled from Galich to Novgorod. In 1453, a clerk sent by Vasily II in Novgorod bribed the cook, and he poisoned Dmitry Shemyaka. Mutiny of Dmitry Shemyaka

There is one area of medieval Rus' where the influence of Tatarism is felt more strongly - at first almost a dot on the map, then an ever-blurring spot that over the course of two centuries covers the entire Eastern Rus'. This is Moscow, the “gatherer” of the Russian land. Owing its rise primarily to the Tatarophile and treacherous policy of its first princes, Moscow, thanks to it, ensures the peace and security of its territory, thereby attracting the working population and luring metropolitans to itself.

The blessing of the Church, now nationalized, sanctifies the successes of dubious diplomacy. Metropolitans, from Russian people and subjects of the Moscow prince, begin to identify their service with the interests of Moscow politics. The church still stands above the state, it leads the state in the person of Metropolitan Alexy (our Richelieu), governing it. National liberation is just around the corner. To speed it up, we are ready to sacrifice elementary justice with a light heart and the foundations of Christian community bequeathed from antiquity. Seizures of territories and treacherous arrests of rival princes are carried out with the support of church threats and interdicts.

In the Moscow land itself, Tatar rules are introduced in administration, court, and collection of tribute. Not from the outside, but from the inside, the Tatar element took possession of the soul of Rus', penetrating into flesh and blood. This spiritual Mongol conquest ran parallel to the political fall of the Horde. In the 15th century, thousands of baptized and unbaptized Tatars went to serve the Moscow prince, joining the ranks of service people, the future nobility, infecting them with oriental concepts and steppe life.

The collection of inheritances itself was carried out by the easternby methods that are not similar to the simultaneous process of eliminating Western feudalism. The entire upper layer of the population was removed and taken to Moscow, all local characteristics and traditions - with such success that the heroic legends of the past were no longer preserved in the people's memory. Which of the Tver, Ryazan, Nizhny Novgorod residents in the 19th century remembered the names of the ancient princes buried in local cathedrals, heard about their exploits, which they could read about on the pages of Karamzin?

The ancient principalities of the Russian land lived only in mocking and humiliating nicknames given to each other. Small homelands have lost all the historical flavor that makes them so beautiful everywhere in France, Germany and England. Rus' becomes solid Muscovy, a monotonous territory of centralized power: a natural prerequisite for despotism.

But old Rus' did not surrender to Muscovy without a fight. Much of the 16th century was filled with noisy disputes and drenched in the blood of the vanquished. The “Trans-Volga elders” and the princely boyars tried to defend spiritual and aristocratic freedom against the Orthodox Khanate.

Collection of articles "New City", New York, 1952.

http://odinblago.ru/rossia_i_svoboda

Many historians have paid attention to the issue of the formation of a centralized state. Special studies by L.V. were dedicated to him. Cherepnin, A.M. Sakharov, A.A. Zimin and many others.

In considering this problem, philosophers were primarily interested in the relationship between the Russian character and the huge and powerful power created by the Russians. “In the soul of the Russian people,” wrote N.A. Berdyaev in the essay “The Russian Idea,” there is the same immensity, boundlessness, aspiration to infinity, as in the Russian plain.” From Rus' was born the mighty Russia.

An interesting concept for the development of this process was proposed by the prominent Russian historian, philosopher, and theologian G.P. Fedotov. In the article “Russia and Freedom” he wrote that Moscow owed its rise to the Tatarophile, treacherous actions of its first princes, that reunification of Rus', the creation of a powerful centralized state was carried out through violent seizures of territory, treacherous arrests of rival princes. And the very “collection” of inheritances, he considered Fedotov, was carried out using eastern methods: the local population was taken to Moscow, replaced by newcomers and strangers, local customs and traditions were uprooted. Fedotov did not deny the need for unification around Moscow, but spoke about “Eastern methods” of this process.

If G.P. Fedotov focused attention on the “Asian forms of unification” of Rus', then N.M. Karamzin- on the progressive nature of the act of unification itself, on the properties of the Russian character. The creation of the Russian state for him is the result of the activities of individual princes and tsars, among whom he especially singled out Ivan III.

IN XIX V. Historians no longer interpreted the processes of creation of the Russian state so straightforwardly; they did not reduce it to the establishment of autocratic power capable of defeating centrifugal forces within the country and Mongol rule. The process of creating a centralized state in Eastern Rus' was considered as a definite result of the ethnic development of the people. The main thing was the statement that during this period the state principle prevailed over the patrimonial principle. Consequently, the development of state institutions of power was associated with the processes taking place in Muscovite Rus'. The very content of the process came down to the struggle of various socio-political forms and the layers of the population behind them. This scheme was embodied in the works of S.M. Solovyov, which gave it historical argumentation, revealing the internal forces of the development of Russian statehood.

IN. Klyuchevsky and his followers supplemented this scheme with the study of socio-economic processes, turning to clarify the role of “social classes”. Russian the nation state has grown, according to V.O. Klyuchevsky, from the “specific order”, from the “patrimony” of princes- descendants of Daniil of Moscow. At the same time, he emphasized that the indiscriminateness of the Moscow princes in political means, their selfish interests made them a formidable force. Moreover, the interests of Moscow rulers coincided with the “people's needs” associated with liberation and the acquisition of independent statehood.

L.V. paid great attention to overcoming the fragmentation of Rus' and creating a centralized state in his works. Cherepnin. In the monograph “The Formation of the Russian Centralized State in the XIV-XV Centuries,” he touched upon a little-studied aspect of this problem - the socio-economic processes that prepared the unification of Rus'. Cherepnin emphasized that the liquidation of “specific orders” took a long time and stretched over the second half of the 16th century, and the turning point in this process was the 80s of the 15th century. During this period, there was a reorganization of the administrative system, the development of feudal law, the improvement of the armed forces, the formation of a service nobility, and the formation of a new form of feudal land ownership - the local system, which formed the material basis of the noble army.

Some historians, considering the features of the formation of the Moscow state, proceed from the concept of the Russian historian M. Dovnar-Zapolsky and American researcher R. Pipes, creators of the concept "patrimonial state". R. Pipes believes that the absence in Russia of feudal structures of the Western European type largely determined the specificity of many processes that took place in North-Eastern Rus'. The Moscow sovereigns treated their kingdom in the same way as their ancestors treated their estates. The emerging Moscow state, represented by its rulers, did not recognize any rights of estates and social groups, which was the basis for the lack of rights of the majority of the population and the arbitrariness of the authorities.

1

Now there is no more painful question than the question of freedom in Russia. Not, of course, in the sense of whether it exists in the USSR - only foreigners, and even those too ignorant, can think about this. But we all now think about whether its revival there after a victorious war is possible - both sincere democrats and semi-fascist fellow travelers. Only straight Black Hundreds, brought up in various “Unions of the Russian People,” feel happy in Ivan the Terrible’s Moscow. The majority of apologists for the Moscow dictatorship - yesterday's socialists and liberals - lull their conscience with confidence in the inevitable and imminent liberation of Russia. The expected evolution of Soviet power allows them to accept with a light heart, and even with glee, the enslavement of more and more peoples of Europe. One can endure a few years of oppression and then live as full participants in the freest and happiest society in the world.

On the other hand, Russia's past does not seem to provide grounds for optimism. For many centuries Russia was the most oppressive monarchy in Europe. Its constitutional - and how frail! - the regime lasted only eleven years; its democracy - and then more in the sense of proclamation of principles than their implementation - some eight months. Having barely freed themselves from the tsar, the people, albeit involuntarily and not without a struggle, submitted to a new tyranny, in comparison with which tsarist Russia seems like a paradise of freedom. Under such conditions, one can understand foreigners or Russian Eurasians who come to the conclusion that Russia organically generates despotism - or fascist "demotism" - from its national spirit or its geopolitical destiny; Moreover, in despotism it is easiest to realize his historical calling.

Are we obliged to choose between these extreme statements: firm faith or firm disbelief in Russian freedom? We belong to those people who passionately yearn for the free and peaceful completion of the Russian revolution. But the bitter experience of life has long taught us not to confuse our desires with reality. Without sharing the doctrine of historical determinism, we admit the possibility of choosing between different options for the historical path of peoples. But on the other hand, the power of the past, the heavy or beneficial burden of traditions, extremely limits this freedom of choice. Now, when, after a revolutionary flight into the unknown, Russia is returning to its historical ruts, its past, more than it seemed yesterday, is fraught with the future. Without dreaming of prophesying, one can try to discern the unclear features of the future in the dim mirror of history.

2

At present, there are not many historians who believe in the universal laws of development of peoples. With the expansion of our cultural horizon, the idea of a diversity of cultural types has prevailed. In my article in No. 8 of the New Journal, I tried to show that only one of them - Christian, Western European - gave birth in its depths to freedom in the modern sense of the word - in the sense in which it now threatens to disappear from the world. I will not return to this topic. Today we are interested in Russia. Answering the question about the fate of freedom in Russia is almost the same as deciding whether Russia belongs to the circle of peoples of Western culture; to such an extent the concept of this culture and freedom coincide in their scope. If not the West, then it is the East? Or something completely special, different from the West and the East? If East, then in what sense is East?

The East, which is always discussed when it is contrasted with the West, is the continuity of the Western Asian cultures, going continuously from Sumerian-Akkadian antiquity to modern Islam. The ancient Greeks fought with him as with Persia, defeated him, but also retreated before him spiritually, until, in the Byzantine era, they submitted to him. The Western Middle Ages fought with him and learned from him in the person of the Arabs. Rus' dealt first with the Iranian, then with the Tatar (Turkic) outskirts of the same East, which at the same time not only influenced, but also directly educated it in the person of Byzantium. Rus' knew the East in two guises: “filthy” (pagan) and Orthodox. But Rus' was created on the periphery of two cultural worlds: East and West. Her relationship with them was very complicated: in the struggle on both fronts, against “Latinism” and against “terrorism,” she looked for allies in one or the other. If she asserted her originality, then more often she meant by it her Orthodox-Byzantine heritage; but the latter was also difficult. Byzantine Orthodoxy was, of course, Orientalized Christianity, but first of all it was Christianity; in addition, a fair amount of Greco-Roman tradition is associated with this Christianity. Both religion and this tradition connected Rus' with the Christian West even when it did not want to hear about this relationship.

In the thousand-year history of Russia, four forms of development of the main Russian theme are clearly distinguished: West - East. First in Kyiv we see Rus' freely accepting the cultural influences of Byzantium, the West and the East. The time of the Mongol yoke is a time of artificial isolation and painful choice between the West and the East (Lithuania and the Horde). Moscow appears to be a state and society of an essentially eastern type, which, however, will soon (in XVII century) begins to seek rapprochement with the West. The new era - from Peter to Lenin - represents, of course, the triumph of Western civilization on the territory of the Russian Empire.

In this article we consider only one aspect of this west-east theme: the fate of freedom in Ancient Rus', in Russia and in the USSR.

3

In the Kievan era, Rus' had all the prerequisites from which the first shoots of freedom sprang up in the West at that time.

Her Church was independent of the state, and the state, of a semi-feudal type - different from that in the West - was just as decentralized, just as deprived of sovereignty.

Christianity came to us from Byzantium and, it would seem, Byzantinism in all senses, including political, was destined as the natural form of the young Russian nation. But Byzantinism is a totalitarian culture, with the sacred nature of state power, firmly holding the Church in its not-too-soft tutelage. Byzantinism excludes any possibility of the emergence of freedom in its depths.

Fortunately, Byzantinism could not be embodied in Kiev society, where all social prerequisites for it were absent. There was not only no emperor (tsar), but also no king (or even grand duke) who could lay claim to power over the Church. The Church in Rus' had its own king, its anointed one, but this king lived in Constantinople. His name was for the Eastern Slavs an ideal symbol of the unity of the Orthodox world - nothing more. The Greek metropolitans themselves, subjects of Byzantium, least of all thought about transferring high royal dignity to the princes of the barbarian peoples. The king - the emperor - is alone in the entire universe. That is why the church sermon on the divine establishment of power has not yet imparted to it either a sacred or an absolute character. The church did not mix with the state and stood high above it. Therefore, she could demand that the bearers of princely power submit to certain ideal principles not only in personal but also in political life: loyalty to contracts, peacefulness, justice. Rev. Theodosius fearlessly denounced the usurper prince, and Metropolitan Nicephorus could declare to the princes: “We have been appointed by God to stop you from bloodshed.”

This freedom of the Church was possible primarily because the Russian Church was not yet national, “autocephalous,” but recognized itself as part of the Greek Church. Its supreme hierarch lived in Constantinople, inaccessible to assassination attempts by local princes. Andrei Bogolyubsky also humbled himself before the Ecumenical Patriarch.

Of course, something else is important. The Old Russian prince did not embody the fullness of power. He had to share it with the boyars, and with the squad, and with the veche. Least of all could he consider himself the master of his land. Besides, he changed it too often. Under such conditions, it was even possible to create a one-of-a-kind Orthodox democracy in Novgorod. From the point of view of freedom, the supremacy of the people's assembly is not essential. The veche itself, no more than the prince, ensured individual freedom. At its rebellious meetings, it sometimes arbitrarily and capriciously dealt with both the lives and property of its fellow citizens. But the very division of powers, which went further in Novgorod than anywhere else, between the prince, the “lord,” the veche and the “lord,” gave here more opportunities for personal freedom. That is why, through the haze of centuries, life in ancient Russian democracy appears to us so free.

During all these centuries, Rus' lived a common life, although soon divided religiously, with the eastern outskirts of the “Latin” world: Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Germany, the Scandinavian countries are not always enemies, but often allies, relatives of the Russian princes - especially in Galich and Novgorod. Their basic Christian and cultural unity with the Eastern Slavs has not been forgotten. The East has turned its predatory face: nomadic Turks, uncultured Iranians, neighbor Russia, devastate its borders, causing tension among all political forces for defense. The East does not seduce with either culture or state organization. The Church does not tire of preaching the need for a common struggle against the “filthy”, and here its voices were listened to more willingly than the warnings against the Latins coming from the Greek hierarchy.

In a word, in Kievan Rus, in comparison with the West, we see no less favorable conditions for the development of personal and political freedom. Its escapes did not receive legal recognition similar to Western privileges. The weakness of the legal development of Rus' is an undoubted fact. But in Novgorod there was also a formal limitation of princely power in the form of an oath. In the Middle Ages, tradition under the name of “fatherland” and “duty” was the best protection of personal rights. The misfortune of Rus' was in something else, exactly the opposite: in the insufficient development of state principles, in the lack of unity. It is hardly possible to talk about appanage Rus' as a single state. It was a dynastic and ecclesiastical unification - politically so

weak, that it did not stand the test of history. Free Rus' became a slave and tributary of the Mongols for centuries.

The two-century Tatar yoke was not yet the end of Russian freedom. Freedom died only after liberation from the Tatars. Only the Moscow Tsar, as the successor of the khans, could put an end to all social forces limiting autocracy. For two or more centuries, Northern Rus', ravaged and humiliated by the Tatars, continued to live its ancient way of life, maintaining freedom on a local scale and, in any case, freedom in its political identity. Novgorod democracy occupied the territory of more than half of Eastern Rus'. In the appanage principalities, the Church and the boyars, if not the veche, which had already fallen silent, shared with the prince responsibility for the fate of the land. The prince still had to listen to lessons in political morality from bishops and elders and listen to the voice of the older boyars. Political immoralism, the result of foreign selfish rule, did not have time to corrupt the entire society, which in its culture even acquires a special spiritual inspiration. The fifteenth century is the golden age of Russian art and Russian holiness. Even “Izmaragds” and other collections of this time are distinguished by their religious and moral freedom from the Moscow and Byzantine Domostroi.

There is one area of medieval Rus' where the influence of Tatarism is felt more strongly - at first almost a dot on the map, then an ever-blurring spot that covers the entire Eastern Rus' for two centuries. This is Moscow, the “gatherer” of the Russian land. Owing its rise primarily to the Tatarophile and treacherous policy of its first princes, Moscow, thanks to it, ensures the peace and security of its territory, thereby attracting the working population and luring metropolitans to itself. The blessing of the Church, now nationalized, sanctifies the successes of dubious diplomacy. Metropolitans, from Russian people and subjects of the Moscow prince, begin to identify their service with the interests of Moscow politics. The church still stands above the state, it leads the state in the person of Metropolitan Alexy (our Richelieu), governing it. National liberation is just around the corner. To speed it up, we are ready with a light heart to sacrifice elementary justice and the foundations of Christian community bequeathed from ancient times. Seizures of territories and treacherous arrests of rival princes are carried out with the support of church threats and interdicts. In the Moscow land itself, Tatar rules are introduced in administration, court, and collection of tribute. Not from the outside, but from the inside, the Tatar element took possession of the soul of Rus', penetrating into flesh and blood. This spiritual Mongol conquest ran parallel to the political fall of the Horde. IN XV century, thousands of baptized and unbaptized Tatars went to serve the Moscow prince, joining the ranks of service people, the future nobility, infecting them with oriental concepts and steppe life.

The collection of inheritances itself was carried out using eastern methods, which were not similar to the simultaneous process of eliminating Western feudalism. The entire upper layer of the population was removed and taken to Moscow, all local peculiarities and traditions - with such success that the heroic legends of the past were no longer preserved in the people's memory. Who from Tver, Ryazan, Nizhny Novgorod in XIX century, remembered the names of the ancient princes buried in local cathedrals, heard about their exploits, which he could read about on the pages of Karamzin? The ancient principalities of the Russian land lived only in mocking and humiliating nicknames given to each other. Small homelands have lost all the historical flavor that makes them so beautiful everywhere in France, Germany and England. Rus' becomes a continuous Muscovy, a monotonous territory of centralized power: a natural prerequisite for despotism.

But old Rus' did not surrender to Muscovy without a fight. Most of XVI centuries filled with noisy disputes and drenched in the blood of the vanquished. The “Trans-Volga elders” and the princely boyars tried to defend spiritual and aristocratic freedom against the Orthodox Khanate. The Russian Church split between the servants of the Kingdom of God and the builders of the Moscow Kingdom. The Osiflans and oprichniki won. The triumph of the party of Joseph Volotsky over the disciples of Nil Sorsky led to the ossification of spiritual life. The victory of the oprichnina, the new “democratic” service class over the clan nobility, meant the barbarization of the ruling layer, the growth of servile self-awareness among it, and even the increased exploitation of the working population. The vanquished undoubtedly belonged to the outgoing strata, those rejected by life. It was a reaction - of conscience and freedom. In this era, “progress” was on the side of slavery. This is enough to seduce the Hegelians - the Solovyovs and other fellow travelers of history. But isn’t it permissible to dwell on one of the turning points of Russian life and ask yourself: what would have happened if the “near council” of the Adashevs, Sylvesters and Kurbskys, relying on the Zemsky Sobor, had managed to begin the era of the Russian representative system? This did not happen. Prince Kurbsky, this Herzen XVI centuries, with a handful of Russian people who escaped from a Moscow prison, they saved the honor of the Russian name in Lithuania with their pen, with their cultural work. The people were not with them. The people did not support the boyars and fell in love with Ivan the Terrible. The reasons are clear. They are always the same when the people support despotism against freedom - under Augustus and in our days: social discord and national pride. The people, of course, had reason to be burdened by dependence on the old masters - and did not think that the power of the new oprichnina nobles brought them serfdom. And, most likely, he was mesmerized by the spectacle of the Tatar kingdoms falling one after another before the Tsar of Moscow. Rus', yesterday's tributary of the Tatars, was reborn into a great eastern power:

And our white king is king above kings,

The hordes all bowed to him.

4

The Moscow autocracy, for all its apparent integrity, was a phenomenon of very complex origin. The Moscow sovereign, like the Prince of Moscow, was a patrimonial owner, “the owner of the Russian land” (that’s what Nicholas was also called II ). But he was also the successor of the conquering khans and Byzantine emperors. Both were called kings in Rus'. This fusion of heterogeneous ideas and means of power created despotism, if not the only one, then rare in history. The Byzantine emperor was in principle a magistrate, voluntarily subject to his own laws. He, although without any reason, was proud of the fact that he reigned over the free, and loved to contrast himself with tyrants. The Moscow Tsar wanted to reign over the slaves and did not feel bound by the law. As Ivan the Terrible said, “I am free to reward my slaves, but I am also free to execute them.” On the other hand, an oriental despot, not bound by law, is bound by tradition, especially religious. In Moscow Ivan IV and subsequently Peter showed how little tradition limits the autocracy of the Moscow Tsar. The Church, which most contributed to the growth and success of the royal power, was the first to pay for it. Metropolitans, appointed in fact by the tsar, were overthrown by him with the greatest ease. One of them, if not two, were killed on the orders of Ivan the Terrible. And in purely church matters, as the Nikon reform showed, the will of the king was decisive. When he wanted to destroy the patriarchate and introduce a Protestant synod in the Russian Church, and this got away with impunity for him.

All classes were attached to the state by service or tax. A man of a free profession was an unthinkable phenomenon in Moscow - except for robbers. Ancient Rus' knew free merchants and artisans. Now all the townspeople were obliged to the state by in-kind duties, lived in a forced organization, transferred from place to place depending on state needs. Serf bondage of the peasantry in Rus' became widespread at the very time when it was dying out in the West, and did not cease to be aggravated to the end XVIII centuries, turning into pure slavery. The entire process of historical development in Rus' became the reverse of Western Europe: it was a development from freedom to slavery. Slavery was dictated not by the whim of the rulers, but by a new national task: the creation of an Empire on a meager economic basis. Only through extreme and general tension, iron discipline, and terrible sacrifices could this impoverished, barbaric, endlessly growing state exist. There is reason to think that people in XVI - XVII centuries better understood the needs and general situation of the state than in XVIII - XIX . Consciously or unconsciously, he made his choice between national power and freedom. Therefore, he is responsible for his own destiny.

In the Tatar school, in the Moscow service, a special type of Russian person was forged - the Moscow type, historically the strongest and most stable of all the changing images of the Russian national person. This type psychologically represents a fusion of northern Great Russians with nomadic steppes, cast in the forms of Osiphlian Orthodoxy. What is most striking about him, especially in comparison with Russian people? XIX century, this is its strength, endurance, extraordinary power of resistance. Without loud military exploits, even without any military spirit - the Kiev poetry of military valor died out in Moscow - the Muscovite created his monstrous Empire with one inhuman labor, endurance, more sweat than blood. This passive heroism, this inexhaustible capacity for sacrifice was always the main strength of the Russian soldier - until the last days of the Empire. The worldview of the Russian person has been simplified to the extreme; even compared to the Middle Ages, the Muscovite is primitive. He does not reason, he takes on faith several dogmas on which his moral and social life rests. But even in religion there is something more important to him than dogma. Ritual, the periodic repetition of legalized gestures, bows, and verbal formulas bind living life, do not allow it to creep into chaos, and even impart to it the beauty of a formalized life. For the Moscow man, like the Russian man in all his incarnations, is not devoid of aesthetics. Only now his aesthetics are becoming heavier. Beauty becomes splendor, plumpness becomes the ideal of feminine beauty. With the eradication of the mystical movements of the Volga region, Christianity is turning more and more into a religion of sacred matter: icons, relics, holy water, incense, bread and Easter cakes. Dietetic nutrition becomes the center of religious life. This is ritualism, but ritualism is terribly demanding and morally effective. In his ritual, as a Jew in law, a Muscovite finds support for sacrificial deeds. The ritual serves to condense moral and social energies.

In Muscovy, moral strength, like aesthetics, appears in the aspect of gravity. Heaviness in itself is neutral - both aesthetically and ethically. Tolstoy is heavy, Pushkin is light. Kyiv was easy, Moscow was hard. But in it, moral gravity takes on anti-Christian features: mercilessness towards the fallen and crushed, cruelty towards the weakened and guilty. "Moscow does not believe in tears". IN XVII century, unfaithful wives are buried in the ground, counterfeiters have their throats poured with lead. At that time, in the West, criminal law reached the limits of inhumanity. But there it was due to the anti-Christian spirit of the Renaissance; in Rus' - the inhumanity of the Byzantine-Osiflan ideal.

It is clear that there could be no place for freedom in this world. Obedience in Joseph's school was the highest monastic virtue. Hence its spread through Domostroy into the life of lay society. Freedom for a Muscovite is a negative concept: a synonym for licentiousness, “punishment,” and disgrace.

Well, what about the “will” that the people dream and sing about, to which every Russian heart responds? The word "freedom" still seems to be a translation of French liberte . But no one can dispute the Russianness of “will”. It is all the more necessary to be aware of the difference between will and freedom for the Russian ear.

Will is, first of all, the opportunity to live, or to live, according to one’s own will, without being constrained by any social ties, not just chains. The will is constrained by equals, and the world is constrained. The will triumphs either in leaving society, in the expanse of the steppe, or in power over society, in violence against people. Personal freedom is unthinkable without respect for the freedom of others; will is always for oneself. It is not the opposite of tyranny, for a tyrant is also a free being. The robber is the ideal of the Moscow will, just as Ivan the Terrible is the ideal of the Tsar. Since will, like anarchy, is impossible in a cultural community, the Russian ideal of will finds expression in the culture of the desert, wild nature, nomadic life, gypsyism, wine, revelry, selfless passion - robbery, rebellion and tyranny.

There is one amazing phenomenon in Moscow XVII century. The people adore the king. There is no hint of political opposition to him, of a desire to participate in power or to get rid of the power of the tsar. And at the same time, starting from the Time of Troubles and ending with the reign of Peter, the entire century lives under the noise of popular - Cossack - Streltsy - riots. Razin's rebellion shook the entire kingdom to its foundations. These riots show that the burden of the state burden was unbearable: in particular, that the peasantry did not reconcile - and never reconciled - with serfdom. When it becomes unbearable, when “the cup of the people’s grief is full,” then the people straighten their backs: beat, rob, take revenge on their oppressors - until the heart departs; the anger will subside, and yesterday’s “thief” himself stretches out his hands to the royal bailiffs: tie me up. Rebellion is a necessary political catharsis for the Moscow autocracy, the source of stagnant forces and passions that cannot be disciplined. Just as in Leskov’s story “Chertogon” a stern patriarchal merchant must go crazy once a year, “drive out the devil” in a wild revelry, so the Moscow people celebrate their “wild will” holiday once a century, after which they return, submissive, to their prison. This was the case after Bolotnikov, Razin, Pugachev, Lenin.

It is not difficult to see what would have happened if Razin or Pugachev had won. The old boyars or nobility would have been exterminated; a new Cossack oprichnina would take his place; S. M. Solovyov and S. F. Platonov would call this the secondary democratization of the ruling class. The position of the serf people would not have changed at all, just as the position of the king would not have changed with the change of dynasty. After all, the Romanovs also ascended the throne with the support of the Cossacks and Tushins. Serfdom was caused by state needs, and state instincts lived vaguely among the Cossacks. The people could only change the king, but not limit him. Moreover, he did not want to take advantage of the self-government that the tsar offered him, and felt as an unnecessary burden participation in zemstvo collections, which could, with a different attitude of the people to state affairs, become the grain of Russian representative institutions. No, the state is a royal matter, not a people's one. The Tsar has all the power, and the boyars, the time will come, the people's tears will flow.

If there was a need for freedom anywhere in Moscow, then, of course, in this most hated boyars. Despite the pogrom of the times of Ivan the Terrible, these freedom-loving sentiments found their way out in attempts to constitutionally limit the power of Tsar Vasily, Vladislav) Mikhail. The boyars sought to protect themselves from royal disgrace and execution without guilt - habeas corpus . And the kings swore allegiance and kissed the cross. The people, who saw their only protection - or revenge - in the tsar's disgrace, did not support it, and the first Russian constitution turned out to be a truly lost charter.

Moscow is not just a two-century episode of Russian history - ending with Peter. For the masses who remained alien to European culture, life in Moscow dragged on until the liberation (1861). We must not forget that the merchants and clergy lived in XIX century with this Moscow way of life. On the other hand, during the era of its very turbulent existence, the Muscovite kingdom developed an extraordinary unity of culture, which was absent in both Kyiv and St. Petersburg. From the royal palace to the last smoking hut, Moscow Rus' lived with the same cultural content, the same ideals. The differences were only qualitative. The same faith and the same prejudices, the same Domostroy, the same apocrypha, the same morals, customs, speech and gestures. There is not only no line between Christianity and paganism (Kyiv) or between Western and Byzantine tradition (St. Petersburg), but even between enlightened and crude faith. It is this unity of culture that gives the Moscow type its extraordinary stability. For many, he even seems to be a symbol of Russianness. In any case, he survived not only Peter, but also the flowering of Russian Europeanism; in the depths of the popular masses it survived until the revolution.

5

It has long been a truism that since the time of Peter, Russia has lived on two cultural floors. A sharp line separated the thin upper layer, living by Western culture, from the masses who remained spiritually and socially in Muscovy. The people included not only the serf peasantry, but the entire commercial and industrial population of Russia, the townspeople, merchants, and, with certain reservations, the clergy. In contrast to the inevitable cultural gradations between classes in the West, as in any differentiated society, in Russia the differences were qualitative, not quantitative. Two different cultures cohabited in Russia XVIII century. One represented a barbarized relic of Byzantium, the other a student’s assimilation of Europeanism. Above the class discord between the nobility and the peasantry there was a wall of misunderstanding between the intelligentsia and the people, which was not torn down until the very end. Once it might have seemed that this dualism, or even the very feeling of the intelligentsia as a special cultural category, was a unique, purely Russian phenomenon. Now, before our eyes, with the Europeanization of India and China, we see that the same phenomenon is happening everywhere at the junction of two ancient and powerful cultures. A look at Russia from the East or, what is the same thing, through the eyes of a Westerner who sees it as “Scythia” is a necessary prerequisite for understanding the Empire. But, having recognized this, it should now be said: the ease with which the Russian Scythians assimilated an enlightenment alien to them is amazing. They learned not only passively, but also actively and creatively. They immediately responded to Peter with Lomonosov, to Rastrelli - with Zakharov, Voronikhin; one hundred and fifty years after Peter's coup - a short period - the brilliant development of Russian science. It is amazing that in the art of words, in the deepest and most intimate of the creations of the national genius (by the way, the same in music), Russia gave its full measure only in XIX century. Had it perished as a nation back in the era of the Napoleonic wars, the world would never have known what it lost with Russia.

This extraordinary flowering of Russian culture in modern times was possible only thanks to the inoculation of Western culture into the Russian wildflower. But this in itself shows that there was a certain affinity between Russia and the West: otherwise an alien element would have crippled and destroyed national life. There were many deformities and deformities. But from Gallicisms XVIII centuries Pushkin grew up; from the barbarism of the 60s - Tolstoy, Mussorgsky and Klyuchevsky. This means that behind the Orientalism of the Moscow type, the ancient strata of Kievo-Novgorod Rus lay untouched, and in them the exchange of spiritual substances with the Christian West easily and freely took place. Could it have been different? Which of us, even now, can indifferently turn over the pages of the Kyiv Chronicle, who does not feel a chill down the back from some of the lines of the eternal “Tale of Igor’s Campaign”?

Along with culture, with science, with the new way of life of the West comes freedom. And at the same time in two forms: in the form of actual emancipation of everyday life and in the form of a political liberation movement.

We usually do not sufficiently appreciate the everyday freedom that Russian society has enjoyed since Peter the Great and which allowed it for a long time not to notice the lack of political freedom. Even Tsar Peter impaled his enemies, Bironov’s executioners also strung up on the rack all those suspected of anti-German feelings, and in the palace, at royal feasts and assemblies, a new secular type of treatment was established, almost equating yesterday’s serf with his master. The St. Petersburg court wanted to be equal to Potsdam and Versailles, and yesterday’s Tsar of Moscow, heir to the khans and basileus, felt like a European sovereign - absolute, like most Western sovereigns, but bound by a new code of morality and decency. We somehow did not realize why the Russian emperor, who had the complete “divine” right to execute without trial or guilt, burn or flog any of his subjects, to take away his fortune, his wife, did not use this right. And it is impossible to imagine that he would use it - even the most despotic of the Romanovs, like Pavel or Nikolai I . The Russian people would probably endure as they did under Ivan IV and Peter I , - perhaps he would still find pleasure in executing hated masters; There were attempts at popular canonization of Paul. But the St. Petersburg emperor constantly looked back at his German cousins; he was brought up in their ideas and traditions. If people bowed at his feet or climbed up to kiss him, it probably did not give him any pleasure. If he forgot himself, carried away by the temptation of autocracy, the nobility reminded him of the need for decent treatment. The nobility, by elevating some sovereigns to the throne or killing others, achieved that the emperor began to call himself the first nobleman.

The agents of power, themselves belonging to the same circle, followed the example from above. The nobleman was free by law from corporal punishment; according to life's unwritten rules, he was free from personal insults. He could be exiled to Siberia, but he could not be hit or cursed. The nobleman develops a sense of personal honor that is completely different from the Moscow concept of family honor and goes back to medieval knighthood.

The decree on the “liberty of the nobility” freed him from mandatory service to the state. From now on, he can devote his leisure time to literature, art, and science. His participation in these professions liberates them too; they really become free professions - even when they are replenished with plebeians, commoners, mainly from the clergy. From the core of the nobility grows the Russian intelligentsia - completely connected with this class with its virtues and vices. Russia (besides China) was the only country in which education gave nobility. Completing a secondary or even semi-secondary school transformed a person from a peasant into a gentleman - that is, into a free one, protected to a certain extent his personality from the arbitrariness of the authorities, and guaranteed him polite treatment both at the police station and in prison. The policeman saluted the student, whom he could beat only on especially rare days - riots. This everyday freedom in Russia was, of course, a privilege, as everywhere else in the early days of freedom. It was an island of St. Petersburg Russia among the Moscow sea. But this island expanded continuously, especially after the liberation of the peasants. It was inhabited by thousands XVIII century, millions - at the beginning of the twentieth. In essence, this everyday freedom was the most real and significant cultural conquest of the Empire, and this conquest was a clear fruit of Europeanization. It was carried out under the constant and stubborn opposition of the “dark kingdom,” that is, old Moscow Rus'.

The fate of political freedom was much sadder. It seemed so close and feasible in XVIII , especially at the beginning XIX century. Then she began to move away and seemed like a chimera, “meaningless dreams” under Alexander III and even Nicholas II . It came too late, when the authority of the monarchy was undermined in all classes of the nation, and the deepening class discord made it extremely difficult to restructure the state on democratic principles.

For a long time, almost until 1905, the nobility was the bearer of political liberalism in our country. Contrary to the Marxist scheme, it was not the bourgeoisie who initiated liberation: remaining culturally in pre-Petrine Rus', it was the main support of the reaction; until the appearance, at the end XIX century. a new type of European educated (manufacturer and banker. But the nobility, if not for the most part, skeletal and uncultured, then among the European educated elites, for a long time alone represented the love of freedom in Russia. Moreover, throughout XVIII century and early XIX Russian constitutionalists are almost exclusively nobles: members of the Supreme Privy Council under Anna, Count Panin under Catherine, under Alexander - Mordvinov, Speransky, a circle of intimate friends of the emperor. For a long time, Sweden, with its aristocratic constitution, inspired the Russian nobility; then the time came for French and English political ideas. If all of Europe were XVIII century lived in the form of a constitutional monarchy, it is very likely that Russia would have borrowed it along with other cultural attributes. After the French Revolution this became difficult. The European political wind blew in reaction, and the Russian emperors had no desire to ascend the scaffold, repeating European gestures.

But the transplantation of political beliefs - of course, possible (cf. Turkey and Japan) - is much more difficult and dangerous than the borrowing of science and art. This was shown by the unsuccessful “plan of the supreme leaders.” An analysis of the events of 1730 shows, firstly, that the majority of the capital's nobility wanted to limit autocracy; secondly, that it did not want this enough to overcome its own disorganization and discord. As a result, they preferred the general equality of lawlessness to the privileges of the leaders. This is the meaning of the events of 1730, and it smells very much of Muscovy. The gentry of that time, in essence, shared the peasant suspicion of the freedom of the masters. Instead of establishing it for a few (for nobles) and then fighting for its expansion to all classes, in the limit - to the entire nation - the only possible historical path - they prefer slavery for everyone. So great is the power of Moscow in the minds of the cultured or semi-cultured descendants of the oprichnina nobility.

The whole drama of the Russian political situation is expressed in the following formula: political freedom in Russia can only be the privilege of the nobility and Europeanized strata (intelligentsia). The people do not need it, moreover, they are afraid of it, because they see in autocracy the best protection from the oppression of their masters. The liberation of the peasants in itself did not solve the issue, because millions of illiterate citizens living in a medieval way of life and consciousness could not build a new Europeanized Russia. Their political will, if it had only been expressed, would have led to the liquidation of St. Petersburg (schools, hospitals, agronomy, factories, etc.) and to a return to Moscow: that is, now to the transformation of Russia into a colony of foreigners. The agreement between the monarchy and the nobility represented the only possibility of limited political freedom. The French Revolution, with its political reflection on December 14, 1825, made this conspiracy impossible. All that remained was to govern Russia with the help of the bureaucracy, which became a new force, according to Speransky’s ideas, under Nicholas I.

Since the time of the Decembrists, partly even in their generation, liberation ideas have been assimilated and developed by people who have been squeezed out or have voluntarily withdrawn from government activities. This completely changes their character: from practical programs they become ideologies. Since the 1930s, they have been grown in the greenhouses of German philosophy, then in the natural and economic sciences. But their source is invariably Western; Russian liberalism, like socialism, has its spiritual roots in Europe: either in the English political tradition, or in French ideology - now France of the 40s - or in Marxism. Russian socialism, already from Herzen, can be painted in the colors of the Russian community or artel; it remains European in the fundamentals of its worldview. This national mimicry was not at all successful for liberalism.

There are two apparent exceptions. Slavophilism of the 40s was undoubtedly a liberal movement and claimed to be national. But upon closer examination it turns out that the source of his love of freedom is still in Germany, and the Russian past is poorly known to him; Russian institutions (Zemsky Sobor, community) are idealized and have little in common with reality. It is not surprising that, having taken root in Russia, Slavophilism soon lost its liberal content. When did it win and ascend to the throne in the person of Alexander III (with Pobedonostsev), it turned out to be a reactionary dead end in a clearly Moscow direction.

In the 60s, it was a fairly broad, but politically unformed movement (non-nihilists), and had a certain national flavor. I mean young Russian ethnography, merging with populism, historians like Kostomarov, Pypin, Shchapov, Aristov; They are joined by a circle of national composers - first of all, of course, Mussorgsky - and the Itinerants in painting: Repin and Surikov. Some of them, like Kostomarov, correctly look for Russian roots in the distant, Trans-Moscow past. Unfortunately, they did not gain much influence in Russian society. Kostomarov defended the vanquished (Novgorod, feudal Rus'). The Russian intelligentsia chose to assimilate the Moscow historical tradition of Metropolitan Macarius and the Degree Book, filtered through Hegel. With extraordinary ease, without feeling all the tragedy of Russian history, she - following Solovyov and Klyuchevsky - accepted the Moscow-Tatar absorption of Rus' as something normal (like European absolutism), expecting with incomprehensible optimism the shoots of Western freedom on this soil. Other radicals were carried away by the element of rebellion, discovering it in the bone heaviness of Moscow. Since then, the students have not stopped singing bandit songs, and “Dubinushka” has become almost the Russian national anthem. But we have seen how little the robber will has in common with freedom. Mussorgsky, Surikov, the idealization of the Cossacks, schism and razinism undoubtedly inspired the revolutionary army. However, if this ideology had directed the revolution, it would have given it a national Black Hundred character.

The 60s, which did so much to emancipate Russia, dealt the political liberation movement a heavy blow. They directed a significant and most energetic part of it - the entire revolutionary movement - along an anti-liberal channel. The commoners, who are beginning to join the noble intelligentsia in a wide wave, do not find political freedom a sufficiently attractive ideal. They want a revolution that would immediately bring universal equality to Russia - at least at the cost of eliminating the privileged classes (the famous 3 million heads). They begin a fierce struggle against noble liberalism - even the liberal socialism of Herzen. Early populism of the 60-70s even considered the constitution in Russia harmful as strengthening the position of the bourgeois classes. Much could be cited to explain this astonishing aberration: the pursuit of the latest cry of Western political fashion, the extreme primitivism of thought divorced from reality, the maximalism characteristic of Russian daydreaming. But there is one, more serious and fatal, motive that is already familiar to us. The commoners stood closer to the people than the liberals. They knew that freedom means nothing to the people; that it is easier to raise it against the bar than against the king. However, their own heart beat in time with the people; equality told them more freedom. Of course, the same Moscow heritage had an impact here too.

Then they wised up. The Narodnaya Volya members have already recognized the struggle for political liberation. At the end of the century, both dominant socialist parties are clearly fighting for democracy. True, Marxism understood its freedom instrumentally, as a means in the struggle for the dictatorship of the proletariat: revealing the “bourgeois background” of the liberation movement, it humiliated and made meaningless freedom in the eyes of the masses, unsophisticated in tactical subtleties. But here it was no longer the old “Russian spirit” that was blowing, but a new Western scent, or draft, that blew from the utopian communism of the 40s into the still unknown and unforeseen kingdom of fascism.

And yet, the fifty years that have passed since the Liberation have changed the entire face of Russia. The intelligentsia has grown tens of times. Already a new worker-peasant intelligentsia was rising to meet it, which sometimes carried out such bright names of Russian culture as Maxim Gorky and Chaliapin on the crest of the wave. In 1905, it seemed that the age-old line between the people and the intelligentsia had disappeared: the people, having lost faith in the tsar, entrusted the intelligentsia with leadership in the struggle for freedom. The transition of the nobility to the camp of reaction was redeemed by the development of a new liberal bourgeoisie. The old zemstvo, a magnificent school of free society, worked admirably in anticipation of its democratization. The trade union and cooperative movement fostered social and labor democracy. The public school, which had already developed a plan for universal education, quickly corrupted the Moscow formation with superficial enlightenment. Already lovers of Russian folklore had to go to Pechora for its remains. Another fifty years, and the final Europeanization of Russia - right down to its deepest layers - would have become a fact. Could it have been different? After all, its “people” were from the same ethnographic and cultural background as the nobility, who successfully went through the same school in XVIII century. Only these fifty years were not given to Russia.

The first touch of the Moscow soul to Western culture is almost always tempered by nihilism; the destruction of old foundations outpaces the positive fruits of education. A person who has lost faith in God and the king loses all the foundations of personal and social ethics. People started talking about hooliganism in the village at the beginning of the century. The teacher becomes the first object of impudent jokes, the intelligentsia as a class - the object of hatred. After the collapse of the 1905 revolution - and the too hasty departure from the people of the leading strata of Russian culture - new strife is emerging. In his almost prophetic articles, Blok listened to the growing roar of popular hatred, which threatened to engulf our brilliant but fragile culture. Sometimes this or that person from the new popular intelligentsia (Karpov in his book “Flame”) threw down a passionate challenge to the old “bourgeois” intelligentsia, with which he had not yet had time to merge, as Gorky or Chaliapin merged (or almost merged). In this perspective, the entire recent development of Russia seems to be a dangerous race at speed: what will prevent it - liberating Europeanization or the Moscow riot, which will drown and wash away young freedom with a wave of popular anger?

Reading Blok, we feel that Russia is threatened not just by a revolution, but by a Black Hundred revolution. Here, on the threshold of catastrophe, it is worth taking a closer look at this latest, anti-liberal reaction of Moscow, which called itself the Black Hundred in Moscow. At one time, this political entity was underestimated because of the barbarity and savagery of its ideology and political means. It contained the most wild and uncultured things in old Russia, but the majority of the episcopate was associated with it. He was blessed by John of Kronstadt and Tsar Nicholas II trusted him more than his ministers. Finally, there is reason to believe that his ideas won during the Russian Revolution and that, perhaps, it will outlive us all.

Behind Orthodoxy and autocracy, that is, behind the Moscow creed, two main traditions are easily distinguished: acute nationalism, which turns into hatred of all foreigners - Jews, Poles, Germans, etc., and an equally acute hatred of intellectuals, in the broadest sense words that unite all the upper classes of Russia. Hatred for Western enlightenment merged with class hatred for the master, nobleman, capitalist, official - for the entire mediastinum between the tsar and the people. The very term “Black Hundred” is taken from the Moscow dictionary, where it means an organization (guild) of the lower poor trading class; to the Moscow ear it must have sounded like “democracy” to Tocqueville. In a word, the Black Hundred is the Russian edition or the first version of National Socialism. With fanatical hatred, with violent actions that easily took on the character of pogrom and rebellion, the movement harbored within itself the potential for razinism. The authorities and the nobility fed him - but at their own cost. The governor could not always cope with him, and the example of Iliodor in Tsaritsino shows how easily a Black Hundred demagogue becomes a revolutionary demagogue. It doesn’t hurt to dwell on this unsightly reaction of defeated Moscow in those fateful years, when it was not without reason that they remembered the old prophecy: St. Petersburg will be empty.

6

During the 28 years of its victorious, albeit difficult existence, the Russian Revolution experienced a huge evolution, went through many zigzags, and changed many leaders. But one thing remained unchanged in it: the constant, from year to year, belittling and strangling of freedom. It seemed that there was nowhere to go further than Lenin’s totalitarian dictatorship. But under Lenin, the Mensheviks waged a legal struggle in the Soviets, there was freedom of political discussion in the party, literature and art suffered little. It’s so strange to remember this now. The point is not, of course, that Lenin, unlike Stalin, was a friend of freedom. But for the man who breathed the air XIX century, although to a lesser extent than for the Russian autocrat, there were some unwritten boundaries of despotism, at least in the form of habits, restrictions, inhibitions. They had to be overcome step by step. So until now, in totalitarian regimes, having introduced torture, they have not yet reached the point of qualified public executions. Foreigners visiting Russia over a period of several years noted the thickening of bondage in the last refuges of free creativity - in the theater, in music, in cinema. While the Russian emigration rejoiced over the national degeneration of the Bolsheviks, Russia was experiencing one of the most terrible stages of its Golgotha. Millions of tortured victims mark a new turn in the dictatorial helm. At the last “national” stage - and, it would seem, it should have inspired the artist - Russian literature reached the limits of naive helplessness and didacticism; a consequence of the loss of the last vestiges of freedom.

The second, and even more formidable phenomenon. As freedom diminishes, so does the struggle for it. Since the echoes of the civil war died down, freedom disappeared from the agenda of opposition movements - while these movements still existed. We saw a lot of Soviet people abroad - students, military personnel, emigrants of the new generation. In almost no one we notice the longing for freedom, the joy of breathing it. The majority even painfully perceive the freedom of the Western world as disorder, chaos, anarchy. They are unpleasantly surprised by the chaos of opinions in the press columns: isn’t there only one truth? They are shocked by the freedom of workers, strikes, and the easy pace of work. “We drove millions through concentration camps to teach them how to work” - this was the reaction of a Soviet engineer when he became acquainted with the unrest in American factories; but he himself is from the machine - the son of a worker or peasant. In Russia, discipline and coercion are neglected and they do not believe in the importance of personal initiative - not only the party does not believe, but also the entire huge new intelligentsia created by it.

It is not just the system of totalitarian education that is responsible for the creation of this anti-liberal man, although we know the terrible power of the modern technical apparatus of social reforging. Another socio-demographic factor was also at work here. The Russian Revolution was a meat grinder unprecedented in history, through which tens of millions of people were passed through. The vast majority of victims, as in the French Revolution, fell to the lot of the people. Not all of the intelligentsia were exterminated; the technically necessary personnel were partially retained. But no matter how blindly the machine of terror sometimes acted, it undoubtedly struck, first of all, elements that represented, at least only morally, resistance to the totalitarian regime: liberals, socialists, people of strong convictions or critical thought, simply independent people. Not only the old intelligentsia, in the sense of the order of love of freedom and love of the people, perished, but also the broad popular intelligentsia generated by it. More precisely, a selection took place. The people's intelligentsia split - one joined the ranks of the Communist Party, the other (the Socialist-Revolutionary-Menshevik) was exterminated. The intelligentsia were simply not seduced by Bolshevism. But those in its ranks who did not want to die or leave their homeland, over the years of unheard-of humiliation, had to kill in themselves the very feeling of freedom, the very need for it: otherwise life would have been simply unbearable. They turned into technicians who live by what they love, but are already completely soulless. The writer doesn’t care what to write about: he is interested in the artistic “how,” so he can accept any social order. The historian receives his patterns ready from some committees: all he has to do is diligently and competently embroider the patterns...

As a result, it would not be an exaggeration to say that the entire freedom-loving formation of the Russian intelligentsia created over two hundred years of the Empire disappeared without a trace. And it was then that the Moscow totalitarian virgin soil appeared beneath it. The new Soviet man was not so much molded in the Marxist school as he emerged into the light of God from the Muscovite kingdom, slightly acquiring a Marxist gloss. Look at the October generation. Their grandfathers lived in serfdom, their fathers flogged themselves in the volost courts. They themselves went to the Winter Palace on January 9 and transferred the entire complex of innate monarchical feelings to the new red leaders.

Let's take a closer look at the features of the Soviet man - of course, the one who is building life, and not crushed underfoot, at the bottom of collective farms and factories, within the confines of concentration camps. He is very strong, physically and mentally, very wholesome and simple, values practical experience and knowledge. He is devoted to the power that raised him from the dirt and made him a responsible master over the lives of his fellow citizens. He is very ambitious and rather callous to the suffering of his fellow man - a necessary condition for a Soviet career. But he is ready to exhaust himself at work, and his highest ambition is to give his life for the team: the party or the homeland, depending on the times. Don't we recognize the service man in all this? 16th century? (not - XVII , when decadence begins). Other historical analogies suggest themselves: a campaigner from the time of Nicholas I , but without the humanity of Christian and European education; an associate of Peter, but without fanatical Westernism, without national self-denial. He is closer to the Muscovite with his proud national consciousness, his country is the only Orthodox, the only socialist - the first in the world: the third Rome. He looks with contempt at the rest, that is, the Western world; does not know him, does not love him and is afraid of him. And, as of old, his soul is open to the East. Numerous “hordes”, joining civilization for the first time, join the ranks of the Russian cultural layer, orientalizing it for the second time.

It may seem strange to talk about the Moscow type when applied to the dynamism of modern Russia. Yes, this is Moscow set in motion, with its heaviness, but without its inertia. However, this movement is along the lines of external construction, mainly technical. Neither the heart nor the thought is deeply moved; there is no trace of what we Russians call wandering, and the French call inquietude . Behind the external stormy (almost always as if military) movement there is an internal calm peace.

We are here with passionate curiosity - we are following the evolution of Soviet man through his conventional, custom-made literature. We watched with joy, bordering on tenderness, as the features of a human face gradually appeared on the mask of the iron Bolshevik robot of the 20s. It may be - and this is even more likely - that it was more an evolution of censorship or the literary policy of the party than of living life. After all, a Soviet man, even with a revolver in his hands, was a man. And they were characteristic of him, probably even when they were considered forbidden. and friendship, and love for a woman, and even love for the homeland. But in a totalitarian system, the state educates people, their feelings, their thoughts, the most intimate ones. And we welcome the official resurrection of humanity, we rejoice, recognizing in the Soviet hero the features of a beloved Russian face.

This evolution is far from complete and occurs with frequent and painful interruptions. Also, the word “evil,” as in the early years of the Cheka, is used in a positive sense; sometimes even the Russian land is called evil. War naturally brought with it the analogy of revenge and cruelty. But the same war awakened the keys of dormant tenderness - for the desecrated homeland, for the woman, wife and mother of the soldier. There are no signs yet of an awakening of religious feeling. The New Religious Policy (NRP) remains within the bounds of pure politics. But this too will come with time. if religion really constitutes an inalienable attribute of man; someday metaphysical hunger will awaken in this primitive creature, who for now lives by the cult of the machine and small personal happiness.

Whether this internal evolution will end with a revival of freedom is another question, to which the experience of history, it seems, does not belong to the instinctive or universal elements of human society. Only the Christian West developed this ideal in its tragic Middle Ages and realized it in recent centuries. Only in communication with the West did Russia during the Empire become infected with this ideal and began to rebuild its life in accordance with it. It seems to follow from this that if a totalitarian corpse can be resurrected to freedom, then living water will have to be sought again in the West.

Many people think that this time Russia has no need to go so far: it has already accumulated in its literature such values of love of freedom that can ignite the sacred fire in new generations. To think so means to terribly overestimate the importance of books in the development of the soul. We glean from books only what our conscious or unconscious self is looking for. Let us remember that Schiller remains a classic in German schools, that the Gospel was read in the darkest and cruelest centuries of Christian history. Commentators or the spirit of the times always come to the rescue to neutralize spiritual poisons. In Russia they have long been reading the classics with enthusiasm, but there, apparently, it does not occur to them to bring the satire of Gogol or Shchedrin into modern times. And is it only the Russian classics who teach love of freedom? Gogol and Dostoevsky were apologists for autocracy, Tolstoy - for anarchy, Pushkin reconciled with the monarchy of Nicholas. How do they read the classics in Soviet Russia? During the days of Lermontov’s anniversary, everyone wrote about the poet of “Valerik” and “Motherland” as a Russian patriot who fought in the Caucasus for Russian great power. In essence, only Herzen of the entire galaxy XIX centuries can teach freedom. But Herzen, it seems, is not held in particular esteem by the Soviet reader.

If the sun of freedom, as opposed to the astronomical luminary, rises from the West, then we should all seriously think about the ways and possibilities of its penetration into Russia. One of the necessary conditions - personal communication - is now extremely facilitated by the war. The war for the liberation of Russia is a two-sided fact. Its victorious end undoubtedly strengthens the regime, proving, by testing on the battlefield, its military superiority to the weakness of democracies. This argument even works on other liberals from the Russian emigration. But, on the other hand, the war opens up the possibility of personal communication with the West for millions of Russian soldiers. In order for the democratic ideas of the West to appeal to Muscovites, two conditions are necessary - essentially, they boil down to one. The West must find support in its ideals for a more successful, more humane solution to the social issue, which until now, for better or worse, has only been solved by dictatorship. Secondly, the Moscow man must find in his comrade, the democratic soldier, the same strength and faith in the ideal of freedom that he himself experiences, or experienced, in the ideal of communism. But this means for a democrat, negatively, intolerance towards any tyranny, no matter what flag it hides behind. Our ancestors, communicating with foreigners, should have blushed for their autocracy and their serfdom. If they had encountered everywhere the same servile attitude towards the Russian Tsar that Europe and America showed towards Stalin, it would not have occurred to them to think about the shortcomings in their home. The flatterers of Stalin and Soviet Russia are now the enemies of Russian freedom. Or in other words: only by fighting for freedom on all world fronts, external and internal, without any “discrimination) and betrayal, can one contribute to a possible, but still far-off liberation Russia.

[G.P.Fedotov]|[ Library "Vekhi" ]

© 2002, Library "Vekhi"

Stability and freedom in a country are inversely related to size and external security, i.e. The larger a country and the more insecure its borders, the less it can afford the luxury of state sovereignty and civil rights.

Russia organically generates despotism - or fascist "demotism" - from its national spirit or its geopolitical destiny; Moreover, in despotism it is easiest to realize one’s historical calling

Personal freedom is unthinkable without respect for the freedom of others; will is always for oneself. It is not the opposite of tyranny, for a tyrant is also a free being. The robber is the ideal of the Moscow will, just as Ivan the Terrible is the ideal of the Tsar.

One of the saddest features of our peculiar civilization is that we are still discovering truths that have become hackneyed in other countries and even among peoples who are in some respects more backward than us.

Petr Chaadaev