In ancient times, the state of Epirus existed in the north-west of Hellas. Its king's name was Pyrrhus. A talented commander, he enriched military affairs with many innovations. He was the first to surround the military camp with a defensive rampart and ditch. Used elephants in combat.

In 281 BC. e. King Pyrrhus started a war with Rome. He landed in Italy and began to win victories. A year later, the Romans equipped an army designed to crush Pyrrhus. In 279 BC. e. The armies of Rome and Epirus met near the town of Ausculus. After a long battle, the Romans withdrew in full battle order.

Victory went to Pyrrhus. But when he counted his losses, he exclaimed: “Another such victory, and I will be left without an army!” Almost half of the tried and true veteran soldiers died on the battlefield.

After some time, the Romans, having rested and brought up their reserves, attacked Pyrrhus and inflicted a crushing defeat on him. And the expression “Pyrrhic victory” became a common noun, meaning “victory similar to defeat.”

Battle of Lützen

There are many such Pyrrhic victories in history. Sometimes even not great losses, but the death of one person led to defeat. During the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), the Swedish army under the command of King Gustav II Adolf was considered invincible. Gustav Adolf himself, an excellent commander and skillful politician, was the idol of Sweden and its army.

On November 16, 1632, near the town of Lützen (near Leipzig), the Swedish army clashed with the imperial troops of Albrecht Wallenstein.

King Gustav Adolf personally led the attack of the Smolland Cavalry Regiment, but was wounded in the arm in the battle, and the attack continued without him. Seven people remained with the wounded king. In the fog, a group of imperial cuirassiers stumbled upon them. In the ensuing skirmish, Gustav Adolf was killed.

But the battle continued. Prince Bernhard of Weimar took command. The Swedes gained the upper hand, and the defeated, but not destroyed, imperial troops were forced to retreat. It seems like a victory. The Swedes occupied Leipzig, seizing rich warehouses there and capturing the wounded abandoned by the imperials. But the death of Gustav Adolf, a skilled politician and commander, soon affected the integrity of the coalition. Allies broke away - Russia, Saxony, Brandenburg and others.

Soon, the hitherto invincible Swedes suffered a crushing defeat in the Battle of Nördlingen and retreated to Poland.

Battle of Gross-Jägersdorf

There were cases when a brilliant victory turned into defeat due to stupidity, or even outright betrayal. During the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), Russian troops defeated the Prussian army of Field Marshal Lewald near Gross-Jägersdorf.

But the commander of the Russian army S.F. Apraksin did not take advantage of the victory. On the contrary, having learned about the illness of Empress Elizabeth and wanting to please the heir to the throne Peter III, an ardent admirer of the Prussian king Frederick II, he gives a treasonous order to retreat beyond the Neman. A hasty retreat turns into a stampede. Guns, ammunition, convoys with food and wounded were abandoned. Prussian cavalrymen pursue Russian units along the entire route. On top of everything else, a smallpox epidemic begins. So a brilliant victory turned into a catastrophic defeat. Apraksin was removed from office and put on trial, but without waiting for it, he died from a blow.

Battle of Isandlwana

And it also happens that victory, instead of demoralizing the enemy and plunging him into dust, on the contrary, embitters the defeated side and forces it to consolidate. On January 22, 1879, during the Anglo-Zulu War, at the Battle of Isandlwana, a 22,000-strong Zulu army under the command of Nchingwayo Khoza destroyed a large British detachment. Of the 1,400 Englishmen, only 60 were saved. The victory at Isandlwana became a pyrrhic one for the Zulus - not only because of the losses they suffered of 3,000 people.

Even those of the British who did not want war began to support the “hawks” in the government and agreed to provide all the resources necessary to defeat the Zulu. Troops were sent to South Africa and invaded Zululand, and soon the Zulu state ceased to exist.

Myshkova River

December 12, 1942. German troops under the command of Field Marshal Erich von Manstein attempted to unblock the Paulus group encircled in Stalingrad. The Soviet command did not expect an attack in this area. The powerful tank formations of General Hermann Hoth were opposed by weakened and exhausted units of the 51st Army and the 4th Mechanized Corps.

Soviet soldiers fought to the death near the village of Verkhne-Kumsky. Fierce and stubborn fighting continued with varying success from December 13 to 19. Our units were almost completely destroyed. But the Nazi losses turned out to be enormous - by December 17, Hoth had only 35 combat-ready tanks left. Only by bringing up the reserve 17th Tank Division were the Germans able to break through to the Myshkova River. There were only 40 kilometers left to Stalingrad, but the moment was lost. Soldiers of the 51st Army and the 4th Mechanized Corps detained the enemy for five days, paying for it with their lives. During this time, the fresh 2nd Guards Army of General Malinovsky arrived, which completely defeated the enemy. So the German victory near the village of Verkhne-Kumsky can safely be called a Pyrrhic victory.

Borodino

And, of course, the classic example of a Pyrrhic victory is the Battle of Borodino. Napoleon's main goal was not a tactical victory, not the capture of Moscow, but the complete defeat and demoralization of the Russian army. And this just did not happen. The Russian army was leaving the Borodino field, wanting to fight again. Of course, the columns were thinned out, the losses were enormous - 44 thousand soldiers. Indeed, the bloodiest one-day battle in history!

The French lost even more - 50 thousand people, including 49 of their best generals. But losses are different from losses.

If the Russian army, being on its territory, quickly received reinforcements, then the French were in a less advantageous position.

General Ermolov said that the French broke their teeth on the Borodino field. But he spoke these words later.

Initially, the retreat from the battlefield and subsequent departure from Moscow was perceived by the army and the people as a heavy defeat. All of Russia reacted extremely negatively to Kutuzov’s decisions. The wounded Prince Bagration tore off his bandages and bled to death, Emperor Alexander defiantly dressed in civilian dress, theatrically declaring that it was now shameful to wear a Russian uniform.

The generals criticized the commander, the officers swore, the soldiers grumbled.

Ermolov subtly slandered and was openly rude. Only a couple of weeks later, when Napoleon began to make unsuccessful attempts at peace, when the French quartermaster detachments began to be exterminated by Russian peasants, when provisions and fodder for horses dried up in Moscow, when the Cossacks and partisans began to drive thousands of crowds of prisoners into the Tarutino camp, the attitude towards Kutuzov became change. Having understood the brilliant strategic idea that drove Napoleon into the Moscow mousetrap, the army and people moved from censure to approval of Kutuzov.

Thus, a skilled chess player, having sacrificed a strong piece, ultimately wins the entire game. Borodino became a Pyrrhic victory for Napoleon. A tactical victory that led to a catastrophic strategic defeat. The beginning of the collapse of his empire.

Pyrrhic victory Pyrrhic victoryAccording to the ancient Greek historian Plutarch, King Pyrrhus of Epirus in 279 BC. e., after his victory over the Romans at Asculum, he exclaimed: “Another such victory, and we are lost.” Another version of the same phrase is known: “Another such victory, and I will be left without an army.”

In this battle, Pyrrhus won thanks to the presence of war elephants in his army, against which at that time the Romans did not yet know how to fight and therefore were powerless against them, “as if before rising water or a destructive earthquake,” as the same Plutarch wrote. The Romans then had to leave the battlefield and retreat to

his camp, which, according to the customs of those times, meant the complete victory of Pyrrhus. But the Romans fought courageously, so the winner that day lost as many soldiers as the vanquished - 15 thousand people. Hence this bitter confession of Pyrrhus.

Contemporaries compared Pyrrhus to a dice player who always makes a successful throw, but does not know how to take advantage of this luck. As a result, this feature of Pyrrhus destroyed him. Moreover, his own “miracle weapon” - war elephants - played an ominous role in his death.

When Pyrrhus's army was besieging the Greek city of Argos, his warriors found a way to infiltrate the sleeping city. They would have captured it completely bloodlessly, if not for Pyrrhus’ decision to introduce war elephants into the city. They did not pass through the gates - the combat towers installed on them were in the way. They began to remove them, then put them back on the animals, which caused a noise. The Argives took up arms, and fighting began in the narrow city streets. There was general confusion: no one heard orders, no one knew who was where, what was happening on the next street. Argos turned into a huge trap for the Epirus army.

Pyrrhus tried to quickly get out of the “captured” city. He sent a messenger to his son, who was standing with a detachment near the city, with an order to urgently break down part of the wall so that the Epirus warriors would quickly leave the city. But the messenger misunderstood the order, and the son of Pyrrhus moved to the city to the rescue of his father. So two oncoming streams collided at the gates - those retreating from the city and those who rushed to their aid. To top it all off, the elephants rebelled: one lay down right at the gate, not wanting to move at all, the other, the most powerful, nicknamed Nikon, having lost his wounded driver friend, began to look for him, rush around and trample both his own and other people’s soldiers. Finally, he found his friend, grabbed him with his trunk, put him on his tusks and rushed out of the city, crushing everyone he met.

In this commotion, Pyrrhus himself died. He fought with a young Argive warrior, whose mother, like all the women of the city, stood on the roof of her house. Being near the scene of the fight, she saw her son and decided to help him. Having broken out a tile from the roof, she threw it at Pyrrhus and hit him in the neck, unprotected by armor. The commander fell and was finished off on the ground.

But, besides this “sadly born” phrase, Pyrrhus is also known for some achievements that enriched the military affairs of that time. So. He was the first to surround the military camp with a defensive rampart and ditch. Before him, the Romans surrounded their camp with carts, and that was how its arrangement usually ended.

Allegorically: a victory that came at a very high price; success equals defeat (ironic).

Encyclopedic Dictionary of winged words and expressions. - M.: “Locked-Press”. Vadim Serov. 2003.

Pyrrhic victory King Pyrrhus of Epirus in 279 BC. defeated the Romans at the Battle of Ausculum. But this victory, as Plutarch (in the biography of Pyrrhus) and other ancient historians say, cost Pyrrhus such great losses in the army that he exclaimed: “Another such victory, and we are lost!” Indeed, in the next year, 278, the Romans defeated Pyrrhus. This is where the expression “Pyrrhic victory” arose, meaning: a dubious victory that does not justify the sacrifices made for it.

Dictionary of popular words. Plutex. 2004.

What does "Pyrrhic victory" mean?

Maxim Maksimovich

There is a region of Epirus in Greece. King Pyrrhus of Epirus in 280 BC. e. waged a long and brutal war with Rome. Twice he managed to win; His army had war elephants, but the Romans did not know how to fight with them. Nevertheless, the second victory was given to Pyrrhus at the cost of such sacrifices that, according to legend, he exclaimed after the battle: “Another such victory - and I will be left without an army!”

The war ended with the defeat and retreat of Pyrrhus from Italy. The words “Pyrrhic victory” have long since become a designation for success, bought at such a high price that, perhaps, defeat would have been no less profitable: “The victories of the fascist troops near Yelnya and Smolensk in 1941 turned out to be “Pyrrhic victories.”

~Fish~

Ausculum, a city in the North. Apulia (Italy), near which in 279 BC. e. There was a battle between the troops of the Epirus king Pyrrhus and the Roman troops during the wars of Rome for the conquest of the South. Italy. The Epirus army broke the resistance of the Romans within two days, but its losses were so great that Pyrrhus said: “one more such victory and I will have no more soldiers left.” Hence the expression “Pyrrhic victory.”

The expression “Pyrrhic victory” also became popular. How did it come about? What does it mean?

Roma Subbotin

Pyrrhic victory

There is a region of Epirus in Greece. King Pyrrhus of Epirus in 280 BC. e. waged a long and brutal war with Rome. Twice he managed to win; His army had war elephants, but the Romans did not know how to fight with them. Nevertheless, the second victory was given to Pyrrhus at the cost of such sacrifices that, according to legend, he exclaimed after the battle: “Another such victory - and I will be left without an army!” The war ended with the defeat and retreat of Pyrrhus from Italy. The words “Pyrrhic victory” have long since become a designation for success, bought at such a high price that, perhaps, defeat would have been no less profitable: “The victories of the fascist troops near Yelnya and Smolensk in 1941 turned out to be “Pyrrhic victories.”

Bulat Khaliullin

The Roman Republic fought with Greece in 200-300 BC. e.

The king of one small Greek state (Epirus) was Pyrrhus

In one of the campaigns, his army defeated the army of Rome, but suffered terrible losses

As a result, he lost the next battle, and then he himself was killed by a piece of a tiled roof during street fighting

Kikoghost

When Pyrrhus in 279 B.C. e. won another victory over the Roman army, examining it, he saw that more than half of the fighters had died. Amazed, he exclaimed: “Another such victory, and I will lose my entire army.” The expression means a victory that is equal to a defeat, or a victory for which too much has been paid.

Nadezhda Sushitskaya

A victory that came at too high a price. Too many losses.

The origin of this expression is due to the battle of Ascullus in 279 BC. e. Then the Epirus army of King Pyrrhus attacked the Roman troops for two days and broke their resistance, but the losses were so great that Pyrrhus remarked: “Another such victory, and I will be left without an army.”

The king who won at too great a cost. What answer?

Afanasy44

Pyrrhic victory- an expression that is included in all dictionaries of the world and appeared more than 2 thousand years ago, when the king of Epirus Pyrrhus was able to defeat the Romans near the town of Ausculum during his raid on the Apennine Peninsula. In a two-day battle, his army lost about three and a half thousand soldiers and only the successful actions of 20 war elephants helped him break the Romans.

King Pyrrhus, by the way, was a relative of Alexander the Great and was his second cousin, so he had someone to learn from. Although in the end he lost the war with the Romans, he returned to his place. And 7 years later, during an attack on Macedonia, he was killed in the city of Argos, when a woman from the city’s defenders threw tiles at him from the roof of a house.

Vafa Aliyeva

Pyrrhic victory - this expression owes its origin to the battle of Ausculum in 279 BC. e. Then the Epirus army of King Pyrrhus attacked the Roman troops for two days and broke their resistance, but the losses were so great that Pyrrhus remarked: “Another such victory, and I will be left without an army.”

Tamila123

We are talking about the king of Epirus and Macedonia - King Pyrrhus. He fought with Ancient Rome. King Pyrrhus suffered great losses, which is why that war became the phraseology “Pyrrhic victory” - a victory on the way to which there were so many losses that the taste of victory is not felt.

Valery146

The Greek king Pyrrhus won the battle with the enemy, losing more than half of his army and realized that one more such victory and he would have no soldiers left.

This is how the expression Pyrrhic victory appeared, that is, a victory achieved at a very high, usually unacceptable price!

It was probably PYRRHUS. Since then, this victory bears his name and is called a Pyrrhic victory, that is, the sacrifices made for this victory in no way correspond to the victory itself, but are equated to defeat. This is approximately how I understand this expression)))

Pyrrhic victory

Pyrrhic victory

According to the ancient Greek historian Plutarch, King Pyrrhus of Epirus in 279 BC. e., after his victory over the Romans at Asculum, he exclaimed: “Another such victory, and we are lost.” Another version of the same phrase is known: “Another such victory, and I will be left without an army.”

In this battle, Pyrrhus won thanks to the presence of war elephants in his army, against which at that time the Romans did not yet know how to fight and therefore were powerless against them, “as if before rising water or a destructive earthquake,” as the same Plutarch wrote. The Romans then had to leave the battlefield and retreat to

his camp, which, according to the customs of those times, meant the complete victory of Pyrrhus. But the Romans fought courageously, so the winner that day lost as many soldiers as the vanquished - 15 thousand people. Hence this bitter confession of Pyrrhus.

Contemporaries compared Pyrrhus to a dice player who always makes a successful throw, but does not know how to take advantage of this luck. As a result, this feature of Pyrrhus destroyed him. Moreover, his own “miracle weapon” - war elephants - played an ominous role in his death.

When Pyrrhus's army was besieging the Greek city of Argos, his warriors found a way to infiltrate the sleeping city. They would have captured it completely bloodlessly, if not for Pyrrhus’ decision to introduce war elephants into the city. They did not pass through the gates - the combat towers installed on them were in the way. They began to remove them, then put them back on the animals, which caused a noise. The Argives took up arms, and fighting began in the narrow city streets. There was general confusion: no one heard orders, no one knew who was where, what was happening on the next street. Argos turned into a huge trap for the Epirus army.

Pyrrhus tried to quickly get out of the “captured” city. He sent a messenger to his son, who was standing with a detachment near the city, with an order to urgently break down part of the wall so that the Epirus warriors would quickly leave the city. But the messenger misunderstood the order, and the son of Pyrrhus moved to the city to the rescue of his father. So two oncoming streams collided at the gates - those retreating from the city and those who rushed to their aid. To top it all off, the elephants rebelled: one lay down right at the gate, not wanting to move at all, the other, the most powerful, nicknamed Nikon, having lost his wounded driver friend, began to look for him, rush around and trample both his own and other people’s soldiers. Finally, he found his friend, grabbed him with his trunk, put him on his tusks and rushed out of the city, crushing everyone he met.

In this commotion, Pyrrhus himself died. He fought with a young Argive warrior, whose mother, like all the women of the city, stood on the roof of her house. Being near the scene of the fight, she saw her son and decided to help him. Having broken out a tile from the roof, she threw it at Pyrrhus and hit him in the neck, unprotected by armor. The commander fell and was finished off on the ground.

But, besides this “sadly born” phrase, Pyrrhus is also known for some achievements that enriched the military affairs of that time. So. He was the first to surround the military camp with a defensive rampart and ditch. Before him, the Romans surrounded their camp with carts, and that was how its arrangement usually ended.

Allegorically: a victory that came at a very high price; success equals defeat (ironic).

Encyclopedic Dictionary of winged words and expressions. - M.: “Locked-Press”. Vadim Serov. 2003.

Pyrrhic victory

King Pyrrhus of Epirus in 279 BC. defeated the Romans at the Battle of Ausculum. But this victory, as Plutarch (in the biography of Pyrrhus) and other ancient historians say, cost Pyrrhus such great losses in the army that he exclaimed: “Another such victory, and we are lost!” Indeed, in the next year, 278, the Romans defeated Pyrrhus. This is where the expression “Pyrrhic victory” arose, meaning: a dubious victory that does not justify the sacrifices made for it.

Dictionary of catch words. Plutex. 2004.

Synonyms:

See what “Pyrrhic victory” is in other dictionaries:

Ushakov's Explanatory Dictionary

PYRRHIC VICTORY. see victory. Ushakov's explanatory dictionary. D.N. Ushakov. 1935 1940 ... Ushakov's Explanatory Dictionary

Noun, number of synonyms: 2 victory (28) defeat (12) ASIS Dictionary of Synonyms. V.N. Trishin. 2013… Synonym dictionary

Pyrrhic victory- wing. sl. King Pyrrhus of Epirus in 279 BC. e. defeated the Romans at the Battle of Ausculum. But this victory, as Plutarch (in the biography of Pyrrhus) and other ancient historians say, cost Pyrrhus such great losses in the army that he... ... Universal additional practical explanatory dictionary by I. Mostitsky

Pyrrhic victory- Book A victory devalued by excessive losses. The impresario jumped up and greeted Rachmaninov with a respectful, comic bow. I admit, you won... But no matter how it turned out to be a Pyrrhic victory. Serious tests await you... The entire collection is from my... ... Phraseological Dictionary of the Russian Literary Language

Pyrrhic victory- stable combination A dubious victory that does not justify the sacrifices made for it. Etymology: After the name of the Epirus king Pyrrhus (Greek Pyrros), who defeated the Romans in 279 BC. e. a victory that cost him huge losses. Encyclopedic... ... Popular dictionary of the Russian language

Pyrrhic victory- A victory that came at the cost of such huge losses that it becomes doubtful or not worth it (from the historical event of the victory of King Pyrrhus over the Romans at the cost of huge losses) ... Dictionary of many expressions

Pyrrhus Campaign A Pyrrhic victory, a victory that came at too great a price; victory is equivalent to defeat. The origin of this expression is due to the battle of Auskul in 2 ... Wikipedia

- (on behalf of the Epirus king Pyrrhus, who won a victory over the Romans in 279 BC that cost him enormous losses) a dubious victory that does not justify the sacrifices made for it. New dictionary of foreign words. by EdwART, 2009 … Dictionary of foreign words of the Russian language

Pyrrhic victory- book. a victory that cost too much sacrifice, and is therefore tantamount to defeat. The expression is associated with the victory of the Epirus king Pyrrhus over the Romans (279 BC), which cost him such losses that, according to Plutarch, he exclaimed: “Another ... ... Phraseology Guide

Books

- Demyansk massacre. "Stalin's missed triumph" or "Hitler's Pyrrhic victory"?", Simakov Alexander Petrovich. This massacre became the longest battle of the Great Patriotic War, which lasted for a year and a half, from September 1941 to March 1943. This bloody battle was fought on both sides announced...

King Pyrrhus. Source: Commons.wikimedia.org

A Pyrrhic victory is a victory that came at too high a price, the result of which did not justify the effort and money invested.

Origin of the expression

The origin of the expression is associated with the battle of Ausculum (in 279 BC). Then the Epirus army of King Pyrrhus attacked the Roman troops for two days and broke their resistance, but the losses were so great that Pyrrhus remarked: “Another such victory, and I will be left without an army.” Another version of the same phrase is known: “Another such victory, and we are lost.”

The Secret of War Elephants

In this battle, Pyrrhus won thanks to the presence of war elephants in his army, against which at that time the Romans did not yet know how to fight and therefore were powerless against them, “as if before rising water or a destructive earthquake,” as he wrote Plutarch. The Romans then had to leave the battlefield and retreat to their camp, which, according to the customs of those times, meant the complete victory of Pyrrhus. But the Romans fought courageously, so the winner that day lost as many soldiers as the vanquished - 15 thousand people.

Predecessors of the expression

Before Pyrrhus, the expression “Cadmean victory” was in use, based on the ancient Greek epic “Seven against Thebes” and found in Plato in his “Laws”. An interpretation of this concept can be found in the ancient Greek writer Pausanias: telling about the Argives’ campaign against Thebes and the victory of the Thebans, he reports:

“... but for the Thebans themselves this matter was not without great losses, and therefore the victory, which turned out to be disastrous for the victors, is called the Cadmean victory.” (c) “Description of Hellas”, book. IX.

Epirus is a geographical and historical region in southeastern Europe between modern Greece and Albania. Epirus was part of ancient Hellas with the rivers Acheron and Kokytos and the Illyrian population. To the north of Epirus was Illyria, to the northeast - Macedonia, to the east - Thessaly.

To the south were the regions of Ambracia, Amphilochia, Acarnania, and Aetolia.

Pyrrhus tried to consolidate his successes on the battlefield with peace. The Romans, however, were not the type to give up after the first setbacks, and refused to enter into an agreement with the king. Despite all the efforts of the diplomat Cineas and the effect that the defeat of the legions in the south had, the Senate was adamant. According to legend, at the moment when the Romans hesitated, Appius Claudius Caecus (the Blind), considered a true example of the Roman spirit, entered the curia. The elderly censor demanded that the Senate stop negotiations with the enemy and continue the war. One way or another, Pyrrhus’s proposals were rejected and now the war had to be waged further.

Appius Claudius Caecus and modern photography of the Appian Way. (pinterest.com)

The king began to devastate Campania, the richest region under Roman control. Only the threat of capturing this important area brought the Latins out of the stupor in which they were after the defeat at Heraclea. Consul Levin strengthened the garrisons of Naples and Capua (the main city of Campania), forestalling the capture of these cities by the Epiriots. By the way, the rapid march of the Romans to the south was helped by the Appian Way, built on the initiative of that same Appius Claudius. All other Roman forces were to head south against Pyrrhus as soon as possible: two more legions were being formed in Rome, and the Senate ordered the war with the Etruscans to end as soon as possible.

The king, intending to lure Levin onto the battlefield, moved north. The commander went through the Campaign, even invaded Latium, but Rome itself did not dare to attack - having learned about the conclusion of the treaty between the Romans and the Etruscans, the king realized that superior enemy forces would be waiting for him at the walls of the city. Despite the defection of many Italians from Rome, he did not want to put up with Pyrrhus, and the king had no choice but to return to Tarentum and begin preparations for the next campaign. On the way to their winter quarters, the Epirus army once again met with the Romans, but it did not come to a battle: Pyrrhus calmly walked south, and the Romans did not dare attack him.

Preparing for a new battle

The winter passed with active preparations on both sides. Pyrrhus, risking his relations with the Greeks, actively recruited them into the army: to defeat Rome it was necessary to gather as many forces as possible. In addition, Pyrrhus diligently prepared his Italian allies for battle, teaching them to act in the “correct” dismembered formation. It must be said that Pyrrhus, on the whole, was well prepared for the new confrontation: his army doubled in size.

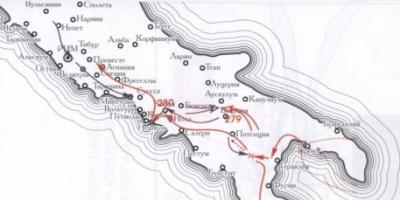

Campaigns of Pyrrhus in Italy. (based on the book by R.V. Svetlov “Pyrrhus and the military history of his time”)

In the campaign of 279 BC. e. Pyrrhus did not strike at the rich but well-defended Campania, but attacked Apulia, a flat region in southern Italy that lay east of Campania. Both consular armies went there, intending to block the paths for the further advance of Pyrrhus. In the summer, the opposing armies met near the town of Auskul in northwestern Apulia. Probably by this time most of the region was already in the hands of the king.

Strengths of the parties

The armies consisted of approximately 30 - 35 thousand infantry, several thousand cavalry (the numerical and qualitative superiority was on the side of the king). Pyrrhus also had 19 elephants in his service. The Romans collected several legions (according to various estimates from 4 to 7), which were reinforced by allied detachments. The allied detachments of the Italics also fought on the side of Pyrrhus - the Greeks (and especially the Epiriots themselves) made up a smaller part of his army.

Not much information has reached us about what the battlefield looked like: it is known that, unlike Heraclea, Pyrrhus was the first to attack the Romans, leaving the camp and crossing the river that crossed the battlefield. The banks of the river were covered with forests, hampering the actions of cavalry and elephants and interfering with the formation of heavily armed Epiriot hoplites. Between the river and the Roman camp there was a plain large enough for both troops to line up there.

Warriors of the army of Pyrrhus of Epirus. (pinterest.com)

We have already briefly mentioned the military affairs of Pyrrhus and Rome, talking about, here we will only point out that the most combat-ready and experienced units of Pyrrhus’s army were the Thessalian horsemen (shock cavalry), the hoplite Hellenistic phalanx and the elite units of the hypaspists (agems), more mobile and lightly armed than the phalanx. The basis of the Roman army at that time was the reformed legion, divided into maniples of hastati, principles and triarii.

By the time of the Battle of Ausculum, the Italics began to play an even more prominent role in the Epirus army, because it was at their expense that Pyrrhus increased his strength. As mentioned above, the king tried to teach the Italians to act in a more organized manner and fight in a dismembered formation.

Battle

On a summer morning in 279 BC. e. King Pyrrhus began to withdraw his troops from the camp, intending to ford the river and force a battle on the Romans on the opposite bank. It is interesting that among ancient authors there are discrepancies even in how long the battle lasted: some writers claim that the battle lasted one day, others that the battle lasted for two days. Today, most historians are inclined to believe that the battle actually lasted two days: on the first, Pyrrhus tried to cross the river, and the Romans gave him a tough rebuff; the main battle took place the next day.

The first day

Pyrrhus encountered difficulties at the very beginning of the battle. The crossing turned out to be not at all as simple as the king expected: the Romans chose a good position for the battle, so that the Epiriot troops, crossing the river, encountered fierce resistance on the enemy side: the cavalry could not gain a foothold on the high wooded bank, and the infantrymen, being under fire , were forced to cover themselves with shields and defend themselves, standing waist-deep in water. The Romans and the Epiriots actually changed roles: a year before, the consul Levin also tried to cross Siris and, having gained a foothold on the other bank, overthrow Pyrrhus and his army.

The Hellenistic phalanx is the striking power of Alexander's heirs. (pinterest.com)

The tenacity of the Romans in defending their shore was so great that on the first day Pyrrhus was unable to cross and deploy his army for battle. On the other hand, the Romans were unable to throw the Epiriots into the river - the latter managed to take a bridgehead on the other side of the river and hold it until nightfall. At night, the legions retreated to the camp, and Pyrrhus’ warriors remained to rest right on the battlefield. The outcome of the battle was to be revealed the next day.

Second day

Pyrrhus's decision to leave the troops to spend the night directly in the field was dictated by the desire to maintain the tactical initiative for the next day. And indeed, when the Roman commanders were just withdrawing the legions from the camp, Pyrrhus’s army was already built and ready for battle. The center of the Epiriots consisted of infantry, to which the king tried to give maximum elasticity: detachments of Italics stood mixed with Greeks, giving flexibility to the formation. The core of the infantry was the phalanx of the Epiriot-Molossians. On the flanks, slightly behind the infantry, the cavalry was located. Some of the horsemen and elephants were withdrawn to reserve.

The Romans lined up similarly: infantry in the center, cavalry on the wings. The consuls planned to “grind” Pyrrhus’s infantry even before introducing elephants into battle. But in case of the appearance of these terrible beasts, which the Roman infantrymen simply refused to fight, it seemed that a solution had been found: the Romans, according to ancient authors, brought hundreds of carts (or chariots) with braziers, torches, tridents and iron scythes onto the battlefield, which were supposed to frighten and injure the elephants. However, in reality everything turned out a little differently.

Fight between phalanx and legion. (pinterest.com)

The battle began with a skirmish of throwers, after which the Romans immediately went on the attack and rushed at Pyrrhus’ infantrymen. A hot battle broke out. The Romans attacked the enemy with all their energy, trying to push him back and break through the Italian front of Pyrrhus. Where the Epirus phalanx fought, the Romans were never able to achieve success, but on the left flank and center, where the Lucans and Samnites, who were inferior to the Romans in training and weapons, fought, the legions managed to push back the enemy. The Tsar, however, skillfully used the flexibility of his army and reserves, transferring them to the threatened direction.

Elephant attack

Finally, when the warriors on both sides were already quite tired of the battle, an indistinct roar and stomping was heard on the Roman flank. It was elephants! Despite the fear that the animals inspired, the Roman commanders remained calm: they relied on chariots with crews.

But Pyrrhus was far from being so simple as to risk the few animals: Elephanteria was assigned a large detachment of archers and throwers and cavalry detachments, which were supposed to clear the way for the elephants. Light maneuverable troops easily dealt with the clumsy chariots, and the elephants, having driven away the enemy horsemen, crashed into the flank of the Roman legions.

Elephants attack the Roman ranks. (pinterest.com)

Pyrrhus, who fought among the infantry, also increased pressure on the enemy maniples and the Romans finally wavered. It seemed impossible to fight against the elephants - you could only run. The animals were compared to a natural disaster - a flood or an earthquake. The Romans fled and took refuge in a camp not far from the battlefield.

The king did not dare to storm the Roman fortifications on the move: his army was tired from the two-day battle, and even noticeably thinned out. In addition, the king himself was wounded (as was the consul Fabricius) and could have lost control of the battle for some time, and fires were already looming in the rear: the Epiriot camp was in danger. It turned out that during the battle, one of the Italic detachments allied to the Romans bypassed the battlefield and attacked the enemy camp, so Pyrrhus had to urgently take measures to save supplies and looted goods. There could no longer be any talk of continuing the battle.

Outcome of the battle

Pyrrhus again defeated the Romans in open battle, face to face, without resorting to ambushes or cunning (except perhaps elephants). The losses of Pyrrhus are usually estimated at 3.5 thousand soldiers, legions - at 6 thousand, however, if these figures take into account losses only among the Epiriotians and Romans themselves (as, for example, researcher R.V. Svetlov believes), then the parties lost at least twice as much soldiers - up to 20 thousand soldiers in total.

Nevertheless, as at Heraclea, the victory came at a high cost to Pyrrhus, at the cost of the death of many of his veterans and associates. Looking around the battlefield, Pyrrhus allegedly exclaimed in his heart: “Another such victory - and I’m dead!” The Romans, despite another painful defeat, were not defeated and still refused to make peace with Pyrrhus until he left Italy.

However, this was not enough for the heirs of Pyrrhus’ enemies: in ancient historiography, the Battle of Ausculum turned from a defeat for the Romans... into a victory! Historian S.S. Kazarov writes about it this way: “... the Romans, defeated on the battlefield, took convincing revenge on the pages of historical works.” In fact, the battle of Ausculum was not such a “Pyrrhic victory” as Roman historiography, hostile to Pyrrhus, tried to present it, although it was to this battle that we owe the appearance of a catchphrase known in ancient times.

What's next?

After Auskul, active hostilities died down for some time. If in the case of the Romans this is easy to explain - they needed time to replenish their strength, and they hardly wanted to fight the overseas king and his monsters in an open field - then why Pyrrhus did not continue the war with all his energy is much more difficult to understand.

Some explain this by the bloodlessness of the king’s army, whose mobilization capabilities were much more modest than those of Rome, while others point to the political situation in the Balkans, where the invasion of the Galatian Celts coincided with the fall of power in Macedonia. Pyrrhus really had to be on his guard in order to react in a timely manner to events overseas.

The Romans deal with the rebel city. (pinterest.com)

On the other hand, the peculiarities of the nature of Pyrrhus affected him - a talented and decisive man, but impatient. And now he has already begun to be burdened by his position in Italy, seeing that the war with Rome is dragging on, and the local Greeks are increasingly seeing him as a tyrant than as a savior. At the same time, another delegation from Syracuse arrived to him, who found themselves surrounded by enemies: in the northeast of the island the Marmetine robbers were rampant, in the west the Carthaginians were seizing more and more lands - they even managed to reach Syracuse itself. The Sicilian Greeks did not have a capable leader, so they repeatedly asked Pyrrhus to come to them and help them fight the enemies of the Hellenes.

The Tsar, stuck in Italy, began to think more and more seriously about an expedition to Sicily. And indeed: after spending another year in the Apennines, waiting for an opportune moment, Pyrrhus went to the island to fight the Punes, giving his expedition the same Pan-Hellenic character as the landing in Italy. But we will tell you about the accomplishments of Pyrrhus in the fight against the ancestors of Hannibal next time. To be continued.