Talcott Parsons (1902-1979) occupies a prominent place in the history of sociology. Thanks to the work of this professor at Harvard University, this discipline was brought to the international level. Parsons created a special style of thinking, which is characterized by a belief in the dominant role of scientific knowledge, reduced to the construction of systems and systematization of data. The main feature of this social thinker is the ability to differentiate, as well as to identify shades of meaning in statements that have already managed to occupy their strong niche in the scientific world, and the ability to invent more and more new and improved analytical schemes.

The researcher approached his ideas, thanks to which T. Parsons’s theory of the social system was released, relying on knowledge of biology, as well as on the works of European sociologists and economists who worked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His teachers and idols were A. Marshall, E. Durkheim, M. Weber and V. Pareto.

main idea

Parsons' theory was an alternative to the Marxist understanding of the primacy of revolution in the global transformation of the world. The work of this scientist is most often rated as “difficult to understand.” However, behind the palisade of complex argumentation and abstract definitions, Parsons' theory reveals one big idea. It lies in the fact that social reality, despite its inconsistency, complexity and immensity, has a systemic character.

T. Parsons was a convinced supporter of the fact that the beginning of scientific sociology was laid at the moment when all the existing connections between people began to be considered by scientists as a single system. The founder of this approach to building society was K. Marx.

In his theory of social action, Parsons built a new theoretical one. He described it in his works under the titles:

- "Social system";

- "The structure of social action";

- "The Social System and the Evolution of the Theory of Action".

The central idea of T. Parsons' theory of social action was the idea that there is a certain state of society when agreement dominates over conflict, that is, consensus takes place. What does this mean? This indicates the organization and orderliness of social actions and the entire social system as a whole.

Parsons' theory has a conceptual framework. Its core is the process of interaction between various social systems. At the same time, it is colored by personal characteristics and limited by the culture of people.

Parsons' theory also addresses social order. According to the author, it contains a number of interrelated meanings. Among them is the idea that there are no accidents in the behavior of each individual. In all human actions there is complementarity, consistency, reciprocity, and, consequently, predictability.

If you carefully study the social theory of T. Parsons, it becomes clear that the author was primarily interested in problems related to changes and destruction of social order. The Harvard professor was able to answer the questions that once worried O. Comte. This scientist, in his writings on “social statics,” focused on self-preservation, stability and inertia of the social order. O. Comte believed that society is capable of resisting external and internal trends aimed at changing it.

T. Parsons' theory is called synthetic. This is due to the fact that it is based on various combinations of factors such as value agreement, individual interest and coercion, as well as on inertial models of the social system.

In Parsons's social theory, conflict is seen as the cause of disorganization and destabilization of social life. Thus, the author identified one of the anomalies. Parsons believed that the main task of the state is to maintain a conflict-free type of relationship between all elements that make up society. This will ensure balance, cooperation and mutual understanding.

Let us briefly consider the theory of the social system of T. Parsons.

Fundamental Concepts

Parsons' theory of action examines the limits that exist in people's actions. While working on his work, the scientist used such concepts as:

- an organism that is the biophysical basis of an individual’s behavior;

- action, which is normatively regulated, goal-directed and motivated behavior;

- an agent expressed by an empirical system of actions;

- a situation, which refers to a zone of the external world that is significant for a person;

- a social system in which there are one or more people among whom interdependent actions occur;

- orientation to the situation, that is, its meaning for the individual, for his standards and plans.

Relationship Objects

The scheme of society considered in Parsons' theory includes the following elements:

- Social facilities.

- Physical objects. These are groups and individuals. They are the means and at the same time the conditions for the implementation of actions by social objects.

- Cultural objects. These elements represent holistic representations, symbols, systems and ideas of beliefs that have constancy and regularity.

Action Elements

Any actor, according to Parsons, always correlates the situation that has arisen with his goals and needs. In this case, the motivational component is connected. This is explained by the fact that in any situation the main goal of the actor is to receive a “reward”.

For the theory of action, motive is not of primary importance. In this case, it is much more important to consider the experience of the actor, that is, his ability to determine the situation in order to organize the optimal impact on it. In this case, not just a reaction should follow. The actor needs to develop his own system of expectations, taking into account the characteristics of the elements of situations.

However, sometimes things can be much more complicated. Thus, in social situations, it is important for the actor to consider those reactions that are possible to manifest from other individuals and groups. This should also be taken into account when selecting your own action option.

In the process of social interaction, symbols and signs that carry a certain meaning begin to play a significant role. They become means of communication for actors. Thus, the experience of social action also includes cultural symbolism.

That is why, in the terminology of Parsons’ theory, personality is an organized system of orientation of the individual. At the same time, along with motivation, those values that serve as components of the “cultural world” are also considered.

Interdependence

How is the system considered in T. Parsons' theory? In his works, the scientist puts forward the idea that any of them, including social ones, has interdependence. In other words, if any changes occur in one part of the system, this will certainly affect it as a whole. The general concept of interdependence in Parsons' social theory is considered in two directions. Let's look at each of them in more detail.

Conditioning factors

What makes up the first of the two directions of interdependence in society? It represents those conditions that contribute to the formation of a hierarchy of conditioning factors. Among them:

- Physical conditions for human existence (life). Without them it is impossible to conduct any activity.

- The existence of individuals. To justify this factor, Parsons gives the example of aliens. If they exist within another solar system, then they are biologically different from humans, and, as a result, lead a different social life from the earthly one.

- Psychophysical conditions. They stand on the third level of the hierarchy and are one of the necessary conditions for the existence of society.

- System of social values and norms.

Controlling Factors

In Parsons' theory of the social system, the second direction of interdependence that takes place in society is also widely disclosed. It is represented by a hierarchy of management and control factors. Adhering to this direction, we can approach the consideration of society from the point of view of the interaction of two subsystems. Moreover, one of them contains energy, and the second - information. What are these subsystems? The first of them in T. Parsons' theory of action is economics. After all, it is this aspect of social life that has high energy potential. At the same time, the economy can be managed by people who do not participate in production processes, but at the same time organize other people.

And here the problem of ideology, norms and values that make it possible to control society becomes of no small importance. A similar function is implemented in the control subsystem (sphere). But this raises another problem. It concerns unplanned and planned management. T. Parsons believed that in this case political power plays a dominant role. It represents the generalizing process with the help of which it is possible to control all other processes occurring in society. Thus, the government is the highest point of the cybernetic hierarchy.

Public subsystems

Parsons' systems theory identifies in society:

- authorities. This institution is necessary to ensure control over what happens on the territory of the state.

- Education and socialization of each person, starting from an early age, as well as control over the population. This subsystem has acquired particular significance nowadays in connection with the emerging problem of information aggression and domination.

- The economic basis of society. It finds its expression in the organization of social production and in the distribution of its product between individuals and segments of the population, as well as in the optimal use of social resources, primarily human.

- The totality of those cultural norms that are embodied in institutions. In slightly different terminology, this subsystem is the maintenance of cultural institutional patterns.

- Communication system.

Social evolution

How does he view Parsons? The scientist has an opinion about what constitutes one of the elements of the development of living systems. In this regard, Parsons argues for the existence of a connection between the emergence of man, considered as a biological species, and the emergence of societies.

According to biologists, humans belong to only one species. That is why Parsons concludes that all communities have common roots, while going through the following stages:

- Primitive. This type of community is characterized by the homogeneity of its systems. Social connections are based on religious and family relationships. Each member of such a society plays a role prescribed to him by society, which, as a rule, depends on the gender and age of the individual.

- Advanced primitive. In this society there is already a division into political, religious and economic subsystems. The role of the individual in this case increasingly depends on his success, which comes with luck or with acquired skills.

- Intermediate. In such a society, a further process of differentiation occurs. It affects systems of social action, necessitating their integration. Writing appears. At the same time, literate people are separated from everyone else. Human values and ideals are freed from religiosity.

- Modern. This stage began in Ancient Greece. At the same time, a system arose, which is characterized by social stratification, which is based on the criterion of success, as well as the development of supporting, integrative, goal-directing and adaptive subsystems.

Prerequisites for the survival of society

In Parsons' theory of action, society is viewed as an integral system. The scientist considers self-sufficiency to be its main criterion, as well as the presence of a high level of self-sufficiency in one’s environment.

When considering the concept of society, Parsons assigned an important place to certain functional prerequisites, which he attributed to:

- adaptability is the ability to adapt to environmental influences;

- maintaining order;

- focus, expressed in the desire to achieve set goals in relation to the environment;

- integration of individuals as active elements.

As for adaptation, Parsons made repeated statements about it, and in different contexts. In his opinion, it is the functional condition that any social system must meet. Only in this case will they be able to survive. The scientist believed that the need for adaptation of an industrial society is satisfied through the development of its specialized subsystem, which is the economy.

Adaptation is the way in which any social system (state, organization, family) is able to manage its environment.

To achieve integration or balance of the social system, there is a centralized value system.

When considering the prerequisites for the survival of society, Parsons developed the idea of M. Weber, who believed that the basis of order is the acceptance and approval by the majority of the population of those norms of behavior that are supported by effective state control.

Changing social systems

Such a process, according to Parsons, is multifaceted and quite complex. All factors influencing changes in the social system are independent of each other. Moreover, none of them can be considered as original. A change in one of the factors will certainly affect the state of all the others. If changes are positive, then we can say that they indicate the ability of society to implement given values.

The social processes occurring in this case can be of three types:

- Differentiation. A striking example of this type of social process is the transition from traditional peasant farming to industrial production that goes beyond the family. There was differentiation in society during the separation of higher education from the church. In addition, a similar type of social process takes place in modern society. It is expressed in the emergence of new classes and strata of the population, as well as in the differentiation of professions.

- Adaptive reorganization. Any group of people must be able to adapt to new conditions. A similar process happened with the family. At one time, she had to adapt to new functions dictated by industrial society.

- Transformation of society. Sometimes society becomes more complex and differentiated. This happens due to the involvement of a wider range of social units. Thus, new elements appear in society with a simultaneous increase in internal connections. It is constantly becoming more complex, and therefore changes its quality level.

T. PARSONS

|

Biography | |

|

Parsons Talcott (1902-1979). American sociologist, creator of the theory of action and the systemic-functional school. Studied at the London School of Economics, Heidelberg University. He proceeded from the fact that spontaneous processes of self-regulation operate in society, maintaining order and ensuring its stability. Self-regulation is ensured by the action of symbolic mechanisms, such as language, values, etc.; normativity, i.e. the dependence of individual action on generally accepted values and norms; and also by the fact that the action is to a certain extent independent of the environment and is influenced by subjective “definitions of the situation.” |

|

|

Religion, from Parsons’ point of view, along with morality and the organs of socialization (family, educational institutions) refers to that subsystem of the social whole that provides the function of reproducing its structure. This is the zone in which the social system interacts most closely at its boundaries with those non-social factors that are closely adjacent to it. These are the cultural and psychological factors that make up the “pattern maintenance” zone. The cultural element is the main factor constituting religion, with its emphasis on values. Parsons notes that secular culture is also capable of performing the function of maintaining models - through the arts, teaching the humanities. Religion, therefore, is a “borderline” education - social and cultural. It refers to cultural phenomena structured around symbolically significant components and their relationships, in and through which social systems and individuals are oriented and directed. Parsons contributed to a certain turn in sociology from "structural functionalism" to "neo-evolutionism" as a modification of general systems theory, which pays great attention to social change and the problems of managing these changes. In the work “A Modern View of Durkheim’s Theory of Religion” (1973), fragments of which are given in the reader quite fully. Parsons interprets Durkheim's theory as an exploration of the place of religion in the system of human action. This work provides an opportunity to become familiar with both the concepts of Durkheim and Parsons himself. Major works: "The Structure of Social Action" (1937), "The Social System" (1952), « Action coordinate system and general theory of action systems. Functional theory of change. The concept of society", “The concept of society: components and their relationships.” |

|

ACTION COORDINATE SYSTEM AND GENERAL THEORY OF ACTION SYSTEMS: CULTURE, PERSONALITY AND PLACE OF SOCIAL SYSTEMS

The subject of this book is the presentation and illustration of a certain conceptual scheme developed for the analysis of social systems from the point of view of a specific frame of reference for action. The book is intended as a theoretical work in the strict sense of the word. It will not directly address issues related to empirical generalizations as such or to questions of methodology, although both will be given a significant place in the contents of the book. Naturally, the value of the conceptual framework proposed here must ultimately be tested by its use in empirical research. Nevertheless, we are not trying here to present our empirical knowledge in a systematic form, which would be necessary for work on general sociology. The focus of this study is the development of a theoretical framework. A systematic review of its empirical use will be undertaken separately.

The main starting point is the concept of social systems of action. What is meant is that interaction individuals occurs in such a way that this process of interaction can be considered as a system in the scientific sense and subjected to theoretical analysis, successfully applied to various types of systems in other sciences.

The main provisions of the action coordinate system have been described in detail earlier, and here they need only be briefly summarized. This coordinate system describes the “orientation” of one or many actors—in the original case, biological organisms—in a situation that includes other actors. This diagram, thus describing the elements of action and interaction, is a diagram relationships. With its help, the structure and processes of systems consisting of the relations of such elements to their situations, including other elements, are analyzed. This scheme concerns internal structures of elements to the extent that the structure directly affects systems of relations.

A situation is defined as that which consists of objects of orientation, i.e. orientation of a given subject of action, differentiates in relation to various objects and their classes that make up his situation. From the point of view of action, it is convenient to classify all objects as corresponding to three classes of objects: social, physical and cultural. A social object is an actor, which, in turn, can be any other individual (“other”), a subject of action who is taken to be the center of the system (“I”), or some collective, which, when analyzing orientation, is considered as something unified. Experiential entities that do not “interact” or “react” to the Self are physical objects. They are the means and conditions for the action of the “I”. Cultural objects are symbolic elements of a cultural tradition, ideas or beliefs, expressive symbols or value standards to the extent that they are considered as objects of a situation on the part of the “I”, and are not “interiorized” as elements included in the structure of his personality.

An action is a certain process in the “subject of action - situation” system that has motivational significance for the acting individual or, in the case of a collective, for the individuals that compose it. This means that the orientation of the corresponding action processes is associated with achieving satisfaction or avoiding troubles on the part of the corresponding subject of action, no matter how specific it may look from the point of view of the structure of a given personality. Only since the attitude towards the situation on the part of the subject of the action will be of a motivational nature in this understanding, it will be considered in this work as an action in the strict sense. It is assumed that the ultimate source of energy or “effort” in processes of action comes from the organism, and according to this, all satisfaction and dissatisfaction have an organic significance. But from the point of view of the theory of action, the specific organization of motivation cannot be analyzed in terms of the needs of the organism, although the roots of motivation are located here. The organization of the elements of action is, first of all, a function of the attitude of the actor to the situation, as well as the history of this attitude, in this sense of “experience”.

The fundamental property of action defined in this way is that it does not consist solely of reactions to the particular “stimuli” of the situation. In addition, the actor develops system expectations related to various objects of the situation. These expectations can only be structured in relation to his own need-despositions and the likelihood of satisfaction or dissatisfaction depending on the action alternatives that the actor can carry out. But in the case of interaction with social objects, new parameters of “I” are added. Part of the “I’s” expectations, in many cases the most significant part, comes down to the likely reactions of the “other” to the possible action of the “I”. This reaction is foreseen in advance and thus influences the “I”’s own choices.

However, at both levels, various elements of the situation acquire special “meanings” for the “I” as “signs” or “symbols” corresponding to the organization of its system of expectations. Signs and symbols, especially where there is social interaction, acquire a common meaning and serve as a means of communication between actors. When symbolic systems arise that can become intermediaries in communication, we speak of the beginnings of culture, which becomes part of the systems of action of the corresponding actors.

Here we will consider only interaction systems that have reached a cultural level. Although the term “social system” can be used in a more elementary sense, this work can neglect this possibility and focus on systems of interaction between multiple actors oriented to a situation where the system includes a generally recognized system of cultural symbols.

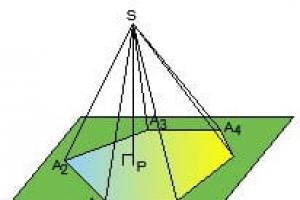

Thus, reduced to its simplest concepts, a social system consists of a number of individual actors interacting with each other in a situation that has at least a physical aspect or is located in some environment of actors whose motivations are determined by the tendency to “optimize” satisfaction ”, and their attitude to the situation, including their attitude towards each other, is determined and mediated by a system of generally accepted symbols that are elements of culture.

Understood in this way, the social system is but one of three aspects of the complex structure of a particular system of action. The other two aspects are the personality systems of the individual actors and the cultural system on which their actions are based. Each of these systems must be considered as an independent axis of organization of the elements of the action system in the sense that none of them can be reduced to the other or to their combination. Each of the systems necessarily presupposes the existence of the others, for without individuals and culture there cannot be a social system. But this interdependence and interpenetration differs in important ways from reducibility, which means that important properties and processes of one class of systems can be theoretically withdrawn from theoretical knowledge of one or two other systems. The coordinate system of action is common to all three, making certain transformations possible between them. But at the theoretical level accepted here, these systems cannot be combined into one, although this may be acceptable at some other theoretical level.

One can come to the same conclusion by arguing that at the current level of theoretical systematization, our dynamic knowledge of action processes is very fragmentary. Therefore, we are forced to use types of empirical systems, descriptively presented in terms of a coordinate system as a necessary reference point. In accordance with this position, we understand dynamic processes by considering them as “mechanisms” that influence the “functioning” of the system. The descriptive representation of an empirical system must be carried out from the point of view of “structural” categories, to which correspond certain motivational formations necessary in order to create useful knowledge about the mechanisms.

Before proceeding to further discussion of the broad methodological problems of the analysis of systems of action, especially the social system, it would be advisable to stop altogether. In the most general sense, the system of needs-attitudes of the individual actor appears to consist of two primary or elementary aspects, which can be called the “satisfaction” aspect and the “orientation” aspect. The first of these concerns the content of the actor's exchange with the world of objects, what he gets from this interaction, and what it is “worth” to him. The second aspect relates to what his relation is to the world of objects, to the types or ways in which his relation to this world is organized.

Isolating the aspect of attitude, we can consider the first aspect as a “cathectic” orientation, which gives significance to the attitude of the “I” to the object or objects in question while maintaining the balance of satisfaction - dissatisfaction of his personality. On the other hand, the most elementary and fundamental category of “orientation” appears to be cognition, which in its broadest sense can be interpreted as the determination of relevant aspects of a situation in their relation to the interests of the actor. This is the cognitive aspect of orientation, or cognitive schematization, according to Tolman. Both of these aspects must be represented in something that can be considered as a unit of a system of action, as a unit act.

But actions are not single and discrete; they are organized into systems. This point, even at the most basic system level, forces us to consider the “system integration” component. From the point of view of the coordinate system of action, this integration is an ordering of the possibilities of orientation through selection. Satisfaction needs are directed toward alternative objects available in the situation. Cognitive schematization faces an alternative judgment or interpretation regarding what an object is or means. There must be a certain order of choice in relation to these alternatives. This process can be called evaluation. Therefore, there is an evaluative aspect to any particular action orientation. The most elementary components of any system of action can be reduced to the actor and his situation. As for the actor, our interests will focus on cognitive, cathectic and evaluative types of orientation; in the situation, objects and their classes will be highlighted.

The elements of action at the broadest level fall under the categories of the three main types of motivational orientation. All three kinds are implied in the structure of what is called expectation. In addition to cathectic interests, cognitive definition of the situation and evaluative selection, expectation includes the temporal aspect of orientation regarding the future development of the “actor-situation” system and memory of past actions. Orientation in a situation has some structure, i.e. it is correlated with its development standards. The actor makes a “contribution” to certain development opportunities. It is important to him how they are implemented, since some opportunities must be realized sooner than others.

This temporary characteristic of the actor’s attitude to the development of the situation can be located on the activity-passivity axis. At one extreme, the actor may simply “wait for development” and not take any active action regarding it. In another case, it may actively try to control the situation in accordance with its desires or interests. The future state of the “actor-situation” system, in which the actor takes a passive position, can be called anticipation. The same state of the system in the case of active intervention (including here the prevention of undesirable events) can be called a goal. Purposefulness of action, as we will see, in particular when discussing normative orientation, is a basic property of all systems of action. However, from an analytical point of view, this goal-directedness seems to be at a lower level than the concept of orientation. Both types must be clearly separated from the concept of “stimulus - “response”, since it does not have an explicit orientation towards the future development of the situation. Stimuli can be viewed as direct data without engaging in theoretical analysis.

The basic concept of the “instrumental” aspect of action can only be used in cases where the action is positively goal-oriented. This concept formulates considerations regarding the situation and the attitude of the actor to it, the alternatives open to him and their possible consequences, which are important for achieving the goal.

Let us briefly look at the initial structure of “need satisfaction”. Of course, the general theory of action must ultimately come to a solution to the question of the unity or qualitative multiplicity of the initial genetically given needs, their classification and organization. In particular, in work dealing with the social system at the level of theory of action, it is highly appropriate to carefully consider the principle of parsimony in such controversial areas. It is necessary, however, to allow for extreme polarization of the structure of needs, which is united in the concept of the balance of satisfaction - dissatisfaction and which has its derivatives in the antithesis of attraction - repulsion. Apart from what has been said above and certain general points about the relations between the satisfaction of needs and other aspects of action, there seems to be no need to proceed to very general concepts.

The main reason for this is that in its significance for sociology, the form of motivation appears to us as organized at the level of the individual, i.e. we are dealing with more specific structures, understood as products of the interaction of genetically given components-needs with social experience. It is uniformity at this level that is empirically significant for sociological problems. In order to use the knowledge of this uniformity, it is not at all necessary to reveal the genetic and experimental components. The main exception here arises in connection with problems of the limits of social variability in the structure of social systems, which can be determined by the biological organization of the corresponding population. Of course, when such problems arise, it is necessary to mobilize all available material in order to formulate a judgment regarding more specific needs for satisfaction.

The problem with this relates not only to need satisfaction, but also to ability. Any empirical analysis of action presupposes biologically determined abilities. We know that they are distributed among individuals in a highly differentiated manner. But from the point of view of the most general theoretical purposes the same principle of economy can be applied here. The validity of this procedure is supported by the knowledge that individual differences are probably more important than differences between large populations, and it is therefore unlikely that the most important differences in large social systems are due primarily to biological differences in the abilities of the population. For most sociological problems, the influence of genes and life experience can be taken into account without isolating them as independent factors.

It has been noted that the most elementary orientation of action in animals presupposes the presence of signs, which are at least the beginning of symbolization. This internality is inherent in the concept of expectation, which includes a certain “distraction” from the particulars of the immediately existing stimulating situation. Without signs, the entire orientational aspect of action would be meaningless, including the concept of “selection” and the “alternatives” that underlie it. At the human level, a certain step has been taken from sign orientation to genuine symbolization. This is a necessary condition for the emergence of culture.

In the basic scheme of action, symbolization is included in both the cognitive orientation and the concept of evaluation. Further elaboration of the role and structure of symbol and action systems involves consideration of the differentiation due to the various aspects of the action system and the aspect of recognition and its relationship to communication and culture. First of all, you need to keep the latter in mind.

However important the neurological premises may be, it seems impossible that true symbolization, as opposed to the use of signs, could arise and function without the interaction of actors, and that an individual actor could acquire symbolic systems only through interaction with social objects. It is at least symptomatic that this fact fits well with the element of “double coincidence” in the interaction process. In classical situations, when an animal learns, it has alternatives to choose from and develops expectations that can become “triggers” through signs or “keys.” But the sign is part of a situation that is stable no matter what the animal does; the only “problem” facing him comes down to the ability to correctly interpret this situation... But in social interaction, the possible reactions of the “other” can acquire significant scope, the choice within which depends on the action of the “I”. So, in order for the interaction process to take shape structurally, the meaning of the sign must be even more abstracted from the particulars of the situation. This means that the meaning of signs must remain constant for a very wide set of circumstances, which covers the area of alternatives not only for the actions of “I”, but also for the “other”, as well as possible changes and combinations of relations between them.

Whatever the origin and development of symbolic systems, it is clear that the amazing complexity of systems of human activity is impossible without relatively stable symbolic systems, the meaning of which is mainly not associated with particular situations. The most important consequence of this generalization is the possibility of communication, since the situations of two actors never are not identical and without the ability to abstract meanings from individual particular situations, communication would be impossible. But in turn, the stabilization of symbolic systems, extending to all individuals throughout time, probably could not be maintained if it did not function in the process of communication in the interaction of many actors. It is precisely this generally accepted symbolic system that functions in interaction that will be called here cultural tradition.

There is a deep connection between these aspects and the normative orientation of action. The symbolic system of knowledge is an element of order, as if superimposed on the real situation. Even the most basic communication is impossible without some degree of agreement with the “conventions” of the symbolic system. To put it somewhat differently, the mutual dependence of expectations is guided by the generally accepted order symbolic meanings. Since the satisfaction of the “I” depends on the reaction of the “other,” a conditional standard begins to be established depending on those conditions that will or will not cause a response of satisfaction, and the relationship between these conditions and reactions becomes part of the significant system of orientation of the “I” to the situation. Therefore, the orientation towards the normative order and the mutual blocking of expectations and sanctions - which is fundamental to our analysis of social systems - are rooted in the deepest foundations of the coordinate system of action.

This basic relationship is common to all types and orientations of interaction. But it is nevertheless important to develop certain distinctions in terms of the relative importance of the three modal elements outlined above:

cathectic, cognitive and evaluative. An element of a generally accepted symbolic system, as a certain criterion or standard for choosing from available orientation alternatives, can be called a value.

In a sense, motivation is an orientation regarding improving the balance of satisfaction - dissatisfaction of the actor. But since action cannot be understood without the cognitive and evaluative components inherent in its orientation from the point of view of the action’s coordinate system, the concept of “motivation will be used here as including all three aspects, and not just the cathectic one. But bearing in mind the role of symbolic systems, it is necessary from this aspect of motivational orientation to distinguish the aspect of value orientation. This aspect concerns not the meaning of the expected state of affairs for the actor in terms of the balance of satisfaction - dissatisfaction, but the content of the standards of choice themselves. In this sense, the concept of value orientation is a logical means for formulating one of the central aspects expressions of cultural tradition in a system of actions.

From the definition of normative orientation and the role of values in action, it follows that all values include what can be called social meaning. Since values are cultural rather than personal characteristics, they tend to be generally accepted. Even if they are indiosyncratic in an individual, still, thanks to their origin, they are determined in connection with the accepted cultural tradition; their originality lies in specific deviations from the general tradition.

However, value standards can be defined not only by their social meaning, but also from the point of view of their functional connections with the action of the individual. All value standards considered in connection with motivation are evaluative in nature. But still in his primary In meaning, standards can be associated with a cognitive definition of a situation, with a cathectic “expression” or with the integration of an action system as some system or part of it. Consequently, value orientation can in turn be divided into three types: cognitive, appreciative and moral standards of value orientation.

Now a few words to explain this terminology. As already noted, this classification is associated with types of motivational orientation. The cognitive aspect of orientation does not cause great difficulties. From the point of view of motivation, the point is in cognitive interest in the situation and its objects, in the motivation for the cognitive determination of the situation. Value orientation positions, on the other hand, concern the standards by which the validity of cognitive judgments is determined. Some of them, like the most elementary laws of logic or rules of observation, may be cultural universals, while other elements are subject to cultural change. In any case, this is the essence of selective evaluation of standards of preference among alternative solutions to problems of cognition or alternative interpretations of phenomena and objects.

The normative object of cognitive orientation is considered obvious. With a cathectic orientation the question is more complicated. The fact is that the attitude towards an object may or may not bring satisfaction to the actor. It should not be forgotten that satisfaction is only part of a system of actions in which the actors are normatively oriented. There is no doubt that this aspect must be considered independently of normative standards of assessment. This is always connected with the question of the correctness and appropriateness of orientation in a given respect in connection with the choice of an object and attitude towards it. Therefore, standards are always included here by means of which choices can be made from possibilities that have cathectic significance.

Socialization theory of T. Parsons- a system of theoretical positions put forward by the American sociologist Talcott Parsons (1902–1979) and reflecting the interpretation of socialization from the standpoint of structural functionalism.

Typically, coverage of Parsons's prominent role in the creation of the great system of structural functionalism obscures his contribution to the development of socialization theory, although it is original and productive for theories of youth. It reveals the influence of B. Malinovsky, with whom Parsons studied at the London School of Economics, and there are parallels with the ideas of P. A. Sorokin, well known to Parsons from Harvard University. It is important that in 1944 Parsons headed the sociology department at Harvard, and in 1946 he participated in the creation of the department of social relations, which, in addition to sociology, also included social anthropology and social and clinical psychology (Parsons headed this department until 1956). His theory of socialization was thus formed at the crossroads of those sciences that include socialization in their subject field, each on its own side, in its own aspect.

Parsons' theoretical positions are the result of the integration of the views of M. Weber, E. Durkheim, V. Pareto, and many other prominent sociologists. Parsons' most important contribution to sociology is recognized as the creation of a general theory of social action and a structural-functional theory of social systems. The “First Great Synthesis,” as Parsons called his theoretical framework (Parsons 1998: 214), was completed with the publication of The Structure of Social Action in 1937, which marked a major turning point in his professional career. Parsons' subsequent generalizing works “The Social System” (1951) and “Toward a General Theory of Action” (1951) secured the author's priority in the development of macrosociology.

However, Parsons's desire to create a theory of society was more than once interrupted by his passion for particular sociological problems, from which, nevertheless, often new impulses to broad general sociological generalizations followed. Thus, after the appearance of The Structure of Social Action, Parsons turned to empirical research on certain issues of medical practice. Influenced by the results obtained, as well as a serious study of the works of S. Freud and then E. Erikson, he develops an original theory of socialization, which he includes in the general theory of social systems.

To understand it, it is important to consider that, according to Parsons, any social system has a set of four functions that ensure its viability. Based on the first letters of the English terms denoting these functions, their system is briefly called AGIL. The first function is designated by Parsons as A (for adaptation). This is an adaptation function. Its purpose is to adapt the system to the environment. It is ensured by rational organization and redistribution of resources in order to ensure the achievement of its goals on this basis. Parsons designated the second function with the letter G (from goal attainment - purposefulness). This is a function of achieving goals. It is also aimed at the external environment, but its purpose is different - to realize the interests of the system, to achieve the implementation of its plan, influencing the environment in its interests. The third function is designated by the letter I (from integration) - this is the integration function. Its purpose is to ensure the cohesion of all elements of the system. And this means that it is necessary to ensure that the new elements that the system is forced to include in its composition to replace the lost, outdated, etc., truly become our own, thus ensuring the continuation of the life of the system in new generations. The fourth function is designated by the letter L (from latent pattern maintenance - preserving the hidden structure). This is a function of shape retention and voltage control. When highlighting this function, Parsons proceeded from the fact that social systems must have a reserve of internal strength and withstand the loads that are created by tense relations between elements (in this case, people). The stability of social systems, according to Parsons, is supported by social institutions. The constant task of the system is to protect it from destruction from the inside. This is achieved by maintaining the patterns on which the system is oriented, i.e. by establishing a certain identity with this system of its elements. It should be noted that another abbreviation of the Parsonian model is found in the literature, namely GAIL, as indicated in the preface to the new edition of “Social systems" by Parsons, written by Brian S. Turner (Turner, 1991: XIX, XXVIII). Parsons, in his 1961 work, outlines his interpretation of this model as follows: “I propose that the basic functional imperatives of any system of action (and therefore of a social system) can be reduced to four imperatives, which I have called conservation of pattern, integration, goal achievement and adaptation. These requirements are listed in descending order of importance from the point of view of cybernetic control of action processes in a system of the type under consideration (Parsons, 2002: 565). Thus, a more accurate designation for Parsons' model would be LIGA.

The American sociologist proceeds in the analysis of socialization from the fact that the basic character of the structure of an individual personality has developed in the process of socialization on the basis of the structure of systems of social objects with which he had connections during his life, including, of course, cultural values and norms institutionalized in these systems ( At the same time, according to Parsons, socialization does not need to be associated with the processes of structural changes in the society in which it occurs). Parsons views this group of “socialization systems” as a “reference group” of systems associated with the process of socialization (Parsons, 1965: 58). The author's thesis is that “the process of socialization goes through a series of stages, defined as preparation for participation in various levels of organization of society; only a select few are prepared to participate with full responsibility at higher levels of the organization. The systems of orientation included in the process of socialization ... represent special varieties of organization at the corresponding levels” (ibid.: 58–59).

Parsons identifies three main stages of the socialization process as applied to American society (each of which is divided into two substages): the first takes place in the family, the second is concentrated in elementary and secondary schools, and the third is in colleges, graduate schools, and professional schools. Having gone through the first main phase of socialization, the child acquires the necessary concept of the main structure of the main family as a social system, which is the prototype of the social system. The theorist suggests that education systems in primary and secondary schools repeat the basic process of socialization at the next, higher level of generalization of the acquired culture and organization of social structure. Thus, secondary school is associated primarily with the differentiation of the difference between instrumental and consummatory types of roles at this level of organization. In this regard, Parsons emphasizes: “It is significant that it is here that a complete “youth culture,” so to speak, appears. The main line of differentiation runs ... between those representatives of the age group who are more oriented towards the achievements of school education and formal “training”, and those who focus mainly on the structure of the peer group, on “leadership”, “popularity”, etc.” (ibid.: 61). According to Parsons, the formal education system serves as a central point in the internalization of a system of higher order social organization than that of the family. This stage of socialization is determined by the influence of “impersonal” and universal forms of control rather than “private” and vague forms of family interaction. In the context of higher education, Parsons notes that here, “all students—both high and low achieving, although they vary widely in their academic work—tend to be held together through a “youth culture,” being in a common school and having a common extracurricular and informal loyalty. This can help build a basis of common solidarity that goes beyond the professional differences that have already emerged" (ibid.: 63).

The most significant thing in the presented concept is that: 1) the process of socialization is associated with a continuous series of reference groups, from which it follows that structural analysis “becomes an important part of the analysis of one of the most “dynamic” social processes - the process of personal development” (ibid.: 65 ); 2) the type of dichotomization is both an important mechanism for placing people within the status structure of society, and at the same time, part of the process of formation of various personality types, which adapt differently to different types of roles, from which follows the closest relationship between personality and social structure; 3) the general structural principle at work is “selection for survival.” “This means,” writes Parsons, “that the process of age group dichotomization distinguishes one group whose members would more willingly remain at a given level of the social hierarchy from another whose members would rather to move on to the next higher level. The group that has been “promoted” is then again subject to the same type of selection pressure and again divided along the same principles. It can be seen that this selection process generally corresponds to the personal needs of a “pyramidal” system in which a relatively large number of people are “needed” at lower levels of the organization and fewer and fewer as one moves to higher levels. The process of selection, including the element of “mobility” and the element of class, is thus most closely connected with the preservation of patterns of stratification of society” (ibid.).

In accordance with this theoretical scheme, Parsons interprets the peer group as an informal group, membership of which is determined by some general social status characteristics (gender, ethnicity, profession, etc.). In research practice, the concept of a peer group is usually applied to age groups of children and youth, especially in relation to adolescent groups, where equality of status becomes extremely important for each member of the group.

Even if Parsons attaches importance to the personal choice of behavioral strategy, he is based on the typical unity of social systems, at whatever level they are formed. Both on a national scale and on a family or friendly company scale, the same functional connections operate. The group uses various methods to preserve itself and rebuild the newcomers that come to it in its own way. Parsons called such methods mechanisms of socialization. They include all the means and processes through which cultural patterns are transmitted by one party and adopted by another. These are language, values, beliefs, symbols. Having mastered them, new group members also change the structure of needs. They get used to new social roles, acquire a taste for fulfilling them, they now not only obey group norms, but want it. It is in this way that the personal system interacts with the social system (Parsons, 1964: 205–208).

So, in Parsons’ concept, socialization is a process that ensures the preservation and functioning of social systems at all levels of social life. Although this process relates to the individual, its origins and consequences are primarily associated with the structures of society and its institutions.

Parsons' socialization theory constitutes his most important contribution to the development of theories of youth, 1996; Lukov, 2007, 2012).

Lit.: , A.I. (1996) Socialization of personality: norm and deviation / Youth Institute. M. 224 pp.; Lukov, V. A. (2007) Education and globalization: Problems of the sociology of education. M.: Flinta: Science. 144 pp.; Lukov, V. A. (2012) Theories of youth: Interdisciplinary analysis. M.: Canon + ROOI “Rehabilitation”. 528 pp.; Parsons, T. (1965) General theoretical problems of sociology // Sociology today: Problems and prospects: American bourgeois sociology of the mid-20th century: abbr. lane from English / total ed. and preface G. V. Osipova. M.: Progress. 684 pp. pp. 25–67; Parsons, T. (1998) The System of Modern Societies. M.: Aspect Press. 270 pp.; Parsons, T. (2002) Essay on a social system // Parsons, T. On social systems. M.: Academic. Project. 832 pp. pp. 543–686; Parsons, T. (1964) The Social System. N.Y., 1964. N.Y.: The free press, 1964. 575 p.; Turner, Br. S. Prefice to the New Edition // Parsons, T. The Social System. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. 404 p. P. XIII–XXX.

Weber's concept of social action was further developed in the works of an American researcher T. Parsons (1902-1979) , the main ones being: “The Structure of Social Action”, “The Social System” and “Towards a General Theory of Action”.

Already from the title of the works it follows that T. Parsons tried to consider the structure of society as a kind of hierarchy of action systems interacting with each other. At the same time, it is characterized by an extremely broad theoretical approach to the analyzed problem, in which the personal and social, individualistic and holistic, biological and societal, rational and irrational, systemic and cybernetic interpretation of a social object are closely intertwined, embodied in the rather abstract concept of “general system” actions”, because it is not specific actions and actions of people that are analyzed, but a certain generalized scheme or model, which is a theoretical construct, which is then superimposed on the real relationships of people and the structure of society. Let's look at this model in more detail.

The general model of social action by T. Parsons is defined by the concept of “single act”.

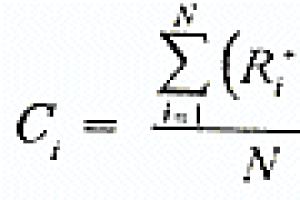

The elements of social action are: 1) actor; 2) the situational environment or environmental factors that are influenced by the factor and have a reverse effect on it; 3) there are four main factors of a “single act”, which are independent systems of action - these are: biological (or physical), cultural, personal Andsocial; 4) each action system is divided into four subsystems; 5) each action system, being open, must satisfy four functionally necessary conditions (prerequisites): adaptation, goal setting, integration and latency, or maintaining a sample; 6) the highest role in the formation of systems and subsystems of action is played by processes socialization Andinstitutionalization; 7) functional relationships between systems and action subsystems are determined through the exchange of symbolic information, which ensures the autonomy of the subsystems and their integration into the whole system; 8) the social significance of systems and subsystems of action is determined by their energy Andinformational potential; 9) the information potential of the system determines its control function: the higher this potential, the stronger this function is manifested; 10) energy and information potentials are inversely proportional to each other.

Thus, the action, according to T. Parsons, has consciously rational, purposeful, selective character. It is influenced by four relatively independent but interacting systems of action (biological, cultural, personal and social). Interaction is carried out on a physical, energy and information basis. Systems at a higher information level play a predominant role in controlling the communication of other systems. Each of the identified systems has its own subsystems of action. All of them are carriers of four main functions and are complemented by coordinate axes that define the framework for the choice of the actor.

Having analyzed the structure of activity in this way, T. Parsons tried to recreate on its basis the structure of society and ways of changing it. His ideas formed the basis of the structural-functional analysis of society, widespread in the West, which was criticized for its formal approach, but, nevertheless, contained a number of productive ideas that served as the starting points for many other sociological concepts.

Talcott Parsons(1902-1979) will be one of the most significant sociologists of the second half of the 20th century, who most fully formulated the foundations of functionalism. In their works, Parsons paid considerable attention to the problem of social order. It is worth noting that he was based on the fact that social life is more characterized by “mutual benefit and peaceful cooperation than mutual hostility and destruction,” arguing that only adherence to common values provides the basis for order in society. He illustrated his views with examples of commercial transactions. When carrying out a transaction, the interested parties draw up a contract based on regulatory rules. From Parsons's perspective, fear of sanctions for breaking rules is not enough to make people follow them strictly. Moral obligations play a major role here. Therefore, the rules governing commercial transactions must follow from generally accepted values, which indicate what will be right and proper. Therefore, order in an economic system is based on general agreement on commercial morality. The sphere of business, like any other component of society, will necessarily be the sphere of morality.

Consensus on values is a fundamental integrative principle in society. From generally accepted values follow general goals, which determine the direction of action in specific situations. For example, in Western society, workers in a particular factory share the goal of efficient production, which follows from a common view of economic productivity. A common goal becomes an incentive for cooperation. The means of translating values and goals into actions will be roles. Any social institution presupposes the presence of a combination of roles, the content of which can be expressed using norms that define the rights and responsibilities in relation to each specific role. Norms standardize and normalize role behavior, making it predictable, which creates the basis of social order.

Based on the fact that consensus is the most important social value, Parsons sees the main task of sociology in the analysis of the institutionalization of patterns of value orientations in the social system. When values are institutionalized and behavior is structured in accordance with them, a stable system emerges—a state of “social equilibrium.” There are two ways to achieve this state: 1) socialization, through which social values are transmitted from one generation to another (the most important institutions that perform this function are the family, the educational system); 2) creation of various mechanisms of social control.

Parsons, considering society as a system, believes that any social system must meet four basic functional requirements:

- adaptation - concerns the relationship between a system and its environment: in order to exist, the system must have a certain degree of control over its environment. It is worth saying that the economic environment is of particular importance for society, which should provide people with the necessary minimum of material goods;

- goal achievement - expresses the need of all societies to set goals towards which social activity is directed;

- integration - refers to the coordination of parts of a social system. The main institution through which this function is realized will be law. Through legal norms, relationships between individuals and institutions are regulated, which reduces the potential for conflict. If a conflict does arise, it should be resolved through the legal system, avoiding the disintegration of the social system;

- sample retention (latency) - involves preserving and maintaining the basic values of society.

Parsons used this structural-functional grid when analyzing any social phenomenon.

Consensus and stability of the system does not mean that it is not capable of change. On the contrary, in practice, no social system is in a state of ideal equilibrium, so the process of social change can be represented as a “fluid equilibrium.” So, if the relationship between society and its environment changes, then this will lead to changes in the social system as a whole.

Sociology of T. Parsons

Talcott Parsons(1902-1979) - American sociologist, very influential in the 20th century, an outstanding representative of structural functionalism. His main works are “The Structure of Social Activity” (1937), “The System of Modern Societies” (1971). It is worth noting that he considered himself a follower of Durkheim, Weber and Freud, who tried to carry out the overdue synthesis of utilitarian (individualistic) and collectivist (socialist) elements of thinking. “The intellectual history of recent years,” writes T. Parsons, “makes, it seems to me, inevitable the following conclusion: the relationship between the Marxist type of thinking and the type of thinking represented by the action theorists at the turn of the twentieth century has the character of a staged sequence in a certain process of development "

Parsons continued to develop Weber's theory of social action. He considers the subject of sociology system of (social) action, which, unlike social action (the action of an individual), contains the organized activity of many people. The action system contains subsystems that perform interrelated functions: 1) social subsystem (group of people) - the function of integrating people; 2) cultural subsystem - reproduction of a pattern of behavior used by a group of people; 3) personal subsystem - goal achievement; 4) behavioral organism - the function of adaptation to the external environment.

The subsystems of the social action system differ functionally, having the same structure. Social subsystem deals with the integration of the behavior of people and social groups. Varieties of social subsystems are societies (family, village, city, country, etc.) Cultural(religious, artistic, scientific) subsystem is engaged in the production of spiritual (cultural) values - symbolic meanings that people, organized into social subsystems, realize in their behavior. Cultural (religious, moral, scientific, etc.) meanings orient human activity (give it meaning). For example, a person goes on the attack, risking his life, to defend his homeland. Personal the subsystem realizes needs, interests, goals in the process of some activity in order to satisfy these needs, interests, and achieve goals. Personality is the main executor and regulator of action processes (sequences of some operations) Behavioral organism is a subsystem of social action, including the human brain, human organs of movement, capable of physically influencing the natural environment, adapting it to the needs of people. Parsons emphasizes that all of the listed subsystems of social action will be “ideal types,” abstract concepts that do not exist in reality. The material was published on http://site

Hence the well-known difficulty in interpreting and understanding T. Parsons.

Parsons views society as a type of social subsystem with the highest degree of self-sufficiency regarding the environment - natural and social. Society consists of four systems - bodies that perform certain functions in the structure of society:

- a societal community consisting of a set of norms of behavior that serves to integrate people into society;

- a subsystem for the preservation and reproduction of a pattern, consisting of a set of values and serving to reproduce a pattern of typical social behavior;

- a political subsystem that serves to set and achieve goals;

- economic (adaptive) subsystem, which includes a set of roles of people in interaction with the material world.

The core of society, according to Parsons, will be societal a subsystem consisting of different people, their statuses and roles, which need to be integrated into a single whole. A societal community is a complex network (horizontal relationships) of interpenetrating typical groups and collective loyalties: families, firms, churches, etc. Note that everyone is type The collective consists of many specific families, firms, etc., which include a certain number of people.

Social evolution, according to Parsons, will be part of the evolution of living systems. Therefore, following Spencer, he argued that there is a parallel between the emergence of man as a biological species and the emergence of modern societies. All people, according to biologists, belong to the same species. Therefore, we can assume that all societies originated from one type of society. All societies go through the following stages: 1) primitive; 2) advanced primitive; 3) intermediate; 4) modern.

Primitive type of society (primitive communal society) is characterized by homogeneity (syncretism) of its systems.

It is worth noting that the basis of social ties is formed by family and religious ties. Members of society have role statuses prescribed to them by society, largely depending on age and gender.

Advanced Primitive society is characterized by division into primitive subsystems (political, religious, economic) The role of prescribed statuses is weakening: people's lives are increasingly determined by their success, which depends on people's abilities and luck.

IN intermediate In societies, further differentiation of systems of social action occurs. There is a need for their integration. There will be a written language that separates the literate from everyone else. On the basis of literacy, information begins to be accumulated, transmitted over a distance, and preserved in the historical memory of the people. The ideals and values of people are separated from religiosity.

Modern society originates in ancient Greece. It is worth noting that it gave rise to a system of modern (European) societies, which are characterized by the following features:

- differentiation of adaptive, goal-directing, integrative, supporting subsystems;

- the basic role of a market economy (private property, mass production, goods market, money, etc.);

- the development of Roman law as the main mechanism for coordination and control of social activities;

- social stratification of society based on the criteria of success (political, economic, cultural)

In every social system, two types of processes occur. It is important to note that some processes - managerial and integrative, which restore balance (stabilization) of the social system after external and internal disturbances. These social processes (demographic, economic, political, spiritual) ensure the reproduction of society and the continuity of its development. Other processes affect the system of basic ideals, values, norms, by which people are guided in social behavior. They are called processes structural changes. It is worth noting that they are deeper and more substantial.

Parsons identifies four mechanisms for the evolution of social systems and societies:

- mechanism differentiation, studied by Spencer, when systems of social action are divided into more specialized ones according to their elements and functions (for example, the production and educational functions of the family were transferred to enterprises and schools);

- increase mechanism adaptability to the external environment as a result of differentiation of social action systems (for example, a farm produces more diverse products, with less labor costs and in larger quantities);

- mechanism integration, ensuring the inclusion of new systems of social action in society (for example, the inclusion of private property, political parties, etc. in post-Soviet society);

- mechanism value generalization, consisting in the formation of new ideals, values, norms of behavior and their transformation into a mass phenomenon (for example, the beginnings of a culture of competition in post-Soviet Russia) The listed mechanisms of societies act together, therefore the evolution of societies, for example, Russian, will be the result of the simultaneous interaction of all these mechanisms .

Parsons examines the evolution of modern (European) societies and does not hide this: “... the modern type of society arose in a single evolutionary zone - in the West<...>Consequently, the society of Western Christendom served as the starting point from which what we call the “system” of modern societies “began.” (In my opinion, along with the Western type of society and the system of these societies, there is an Asian type of society and a system of Asian societies. The latter have significant differences from Western ones.)

From what has been said, we can conclude that Parsons’ sociology will be largely meta-subjectivist in the sense that Hayek puts into the concept of ϶ᴛᴏ. By the way, this sociology pays main attention to the subjective component of social activity; considers collectivist to be the leading form of social activity; refuses to interpret social phenomena by analogy with the laws of nature; does not recognize universal laws of social development; does not seek to design the reconstruction of societies on the basis of open laws.