After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 under the blows of the Germanic tribes, the Eastern Empire was the only surviving power that preserved the traditions of the Ancient World. The Eastern or Byzantine Empire managed to preserve the traditions of Roman culture and statehood over the years of its existence.

Foundation of Byzantium

The history of the Byzantine Empire begins with the founding of the city of Constantinople by the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great in 330. It was also called New Rome.

The Byzantine Empire turned out to be much stronger than the Western Roman Empire in terms of a number of reasons :

- The slave system in Byzantium in the early Middle Ages was less developed than in the Western Roman Empire. The population of the Eastern Empire was 85% free.

- In the Byzantine Empire there was still a strong connection between the countryside and the city. Small-scale farming was developed, which instantly adapted to the changing market.

- If you look at the territory that Byzantium occupied, you can see that the state included extremely economically developed regions at that time: Greece, Syria, Egypt.

- Thanks to a strong army and navy, the Byzantine Empire quite successfully withstood the onslaught of barbarian tribes.

- Trade and crafts were preserved in the large cities of the empire. The main productive force were free peasants, artisans and small traders.

- The Byzantine Empire adopted Christianity as its main religion. This made it possible to quickly establish relationships with neighboring countries.

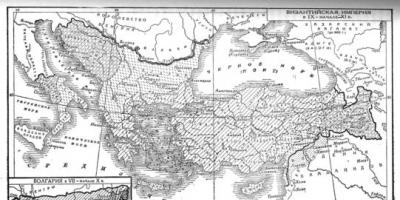

Rice. 1. Map of the Byzantine Empire in the 9th and early 11th centuries.

The internal structure of the political system of Byzantium was not very different from the early medieval barbarian kingdoms in the West: the power of the emperor rested on large feudal lords, consisting of military leaders, Slavic nobility, former slave owners and officials.

Timeline of the Byzantine Empire

The history of the Byzantine Empire is usually divided into three main periods: Early Byzantine (IV-VIII centuries), Middle Byzantine (IX-XII centuries) and Late Byzantine (XIII-XV centuries).

TOP 5 articleswho are reading along with this

Speaking briefly about the capital of the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople, it should be noted that the main city of Byzantium rose even more after the absorption of the Roman provinces by barbarian tribes. Until the 9th century, buildings of ancient architecture were built, and exact sciences were developed. The first higher school in Europe opened in Constantinople. The Church of Hagia Sophia became a real miracle of human creation.

Rice. 2. Temple of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople.

Early Byzantine period

At the end of the 4th and beginning of the 5th centuries, the borders of the Byzantine Empire covered Palestine, Egypt, Thrace, the Balkans and Asia Minor. The Eastern Empire was significantly ahead of the Western barbarian kingdoms in the construction of large cities, as well as in the development of crafts and trade. The presence of a merchant and military fleet made Byzantium a major maritime power. The heyday of the empire continued until the 12th century.

- 527-565 reign of Emperor Justinian I.

The emperor proclaimed the idea or recornista: “Restoration of the Roman Empire.” To achieve this goal, Justinian waged wars of conquest with the barbarian kingdoms. The Vandal states in North Africa fell under the blows of Byzantine troops, and the Ostrogoths in Italy were defeated.

In the occupied territories, Justinian I introduced new laws called the “Justinian Code”; slaves and columns were transferred to their former owners. This caused extreme discontent among the population and later became one of the reasons for the decline of the Eastern Empire.

- 610-641 The reign of Emperor Heraclius.

As a result of the Arab invasion, Byzantium lost Egypt in 617. In the east, Heraclius abandoned the fight against the Slavic tribes, giving them the opportunity to settle along the borders, using them as a natural shield against the nomadic tribes. One of the main merits of this emperor is the return to Jerusalem of the Life-Giving Cross, which was captured from the Persian king Khosrow II. - 717 Arab siege of Constantinople.

For almost a whole year, the Arabs unsuccessfully stormed the capital of Byzantium, but in the end they failed to take the city and rolled back with heavy losses. In many ways, the siege was repulsed thanks to the so-called “Greek fire.” - 717-740 Reign of Leo III.

The years of the reign of this emperor were marked by the fact that Byzantium not only successfully waged wars with the Arabs, but also by the fact that Byzantine monks tried to spread the Orthodox faith among Jews and Muslims. Under Emperor Leo III, the veneration of icons was prohibited. Hundreds of valuable icons and other works of art related to Christianity were destroyed. Iconoclasm continued until 842.

At the end of the 7th and beginning of the 8th centuries, a reform of self-government bodies took place in Byzantium. The empire began to be divided not into provinces, but into themes. This is how the administrative districts headed by the strategists began to be called. They had power and held court on their own. Each theme was obliged to field a militia-stratum.

Middle Byzantine period

Despite the loss of the Balkan lands, Byzantium is still considered a powerful power, because its navy continued to dominate the Mediterranean Sea. The period of the highest power of the empire lasted from 850 to 1050 and is considered the era of “classical Byzantium”.

- 886-912 Reign of Leo VI the Wise.

The emperor followed the policies of previous emperors; Byzantium, during the reign of this emperor, continues to defend itself from external enemies. A crisis was brewing within the political system, which was expressed in the confrontation between the Patriarch and the Emperor. - 1018 Bulgaria joins Byzantium.

The northern borders can be strengthened thanks to the baptism of the Bulgarians and Slavs of Kievan Rus. - In 1048, the Seljuk Turks, led by Ibrahim Inal, invaded Transcaucasia and took the Byzantine city of Erzurum.

The Byzantine Empire did not have enough forces to protect the southeastern borders. Soon the Armenian and Georgian rulers recognized themselves as dependent on the Turks. - 1046 Peace Treaty between Kievan Rus and Byzantium.

Emperor of Byzantium Vladimir Monomakh married his daughter Anna to the Kyiv prince Vsevolod. Relations between Rus' and Byzantium were not always friendly; there were many aggressive campaigns of ancient Russian princes against the Eastern Empire. At the same time, one cannot fail to note the enormous influence that Byzantine culture had on Kievan Rus. - 1054 The Great Schism.

There was a final split between the Orthodox and Catholic Churches. - 1071 The city of Bari in Apulia was taken by the Normans.

The last stronghold of the Byzantine Empire in Italy fell. - 1086-1091 The war of the Byzantine Emperor Alexei I with the alliance of the Pecheneg and Cuman tribes.

Thanks to the cunning policy of the emperor, the alliance of nomadic tribes disintegrated, and the Pechenegs were decisively defeated in 1091.

From the 11th century, the gradual decline of the Byzantine Empire began. The division into themes became obsolete due to the growing number of large farmers. The state was constantly exposed to attacks from the outside, no longer able to fight numerous enemies. The main danger was the Seljuks. During the clashes, the Byzantines managed to clear them from the southern coast of Asia Minor.

Late Byzantine period

Since the 11th century, the activity of Western European countries has increased. The Crusader troops, raising the flag of the “defenders of the Holy Sepulcher,” attacked Byzantium. Unable to fight numerous enemies, the Byzantine emperors used armies of mercenaries. At sea, Byzantium used the fleets of Pisa and Venice.

- 1122 The troops of Emperor John II Komnenos repelled the Pecheneg invasion.

There are continuous wars with Venice at sea. However, the main danger was the Seljuks. During the clashes, the Byzantines managed to clear them from the southern coast of Asia Minor. In the fight against the crusaders, the Byzantines managed to clear Northern Syria. - 1176 Defeat of the Byzantine troops at Myriokephalos from the Seljuk Turks.

After this defeat, Byzantium finally switched to defensive wars. - 1204 Constantinople fell under the attacks of the crusaders.

The core of the crusader army was the French and Genoese. Central Byzantium, occupied by the Latins, is formed into a separate autonomy and is called the Latin Empire. After the fall of the capital, the Byzantine Church was under the jurisdiction of the pope, and Tomazzo Morosini was appointed supreme patriarch. - 1261

The Latin Empire was completely cleared of the crusaders, and Constantinople was liberated by the Nicaean emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos.

Byzantium during the reign of the Palaiologos

During the reign of the Palaiologans in Byzantium, a complete decline of cities was observed. The dilapidated cities looked especially shabby against the backdrop of flourishing villages. Agriculture experienced a boom caused by high demand for the products of feudal estates.

The dynastic marriages of the Palaiologans with the royal courts of Western and Eastern Europe and the constant close contact between them became the reason for the appearance of their own heraldry among the Byzantine rulers. The Palaiologan family was the first to have its own coat of arms.

Rice. 3. Coat of arms of the Palaiologan dynasty.

- In 1265, Venice monopolized almost all trade in Constantinople.

A trade war broke out between Genoa and Venice. Often, stabbings between foreign merchants took place in front of local onlookers in city squares. By strangling the domestic sales market, the emperor's Byzantine rulers caused a new wave of self-hatred. - 1274 Conclusion of Michael VIII Palaiologos in Lyon of a new union with the pope.

The union carried the conditions of the supremacy of the Pope over the entire Christian world. This completely split society and caused a series of unrest in the capital. - 1341 Revolt in Adrianople and Thessalonica of the population against the magnates.

The uprising was led by zealots (zealots). They wanted to take land and property from the church and magnates for the poor. - 1352 Adrianople was captured by the Ottoman Turks.

They made it their capital. They took the Tsimpe fortress on the Gallipoli Peninsula. Nothing prevented the further advance of the Turks into the Balkans.

By the beginning of the 15th century, the territory of Byzantium was limited to Constantinople with its districts, part of Central Greece and islands in the Aegean Sea.

In 1452, the Ottoman Turks began the siege of Constantinople. On May 29, 1453 the city fell. The last Byzantine emperor, Constantine II Palaiologos, died in battle.

Despite Byzantium's alliance with a number of Western European countries, it was impossible to count on military assistance. Thus, during the siege of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453, Venice and Genoa sent six warships and several hundred people. Naturally, they could not provide any significant help.

What have we learned?

The Byzantine Empire remained the only ancient power that retained its political and social system, despite the Great Migration. With the fall of Byzantium, a new era begins in the history of the Middle Ages. From this article we learned how many years the Byzantine Empire lasted and what influence this state had on the countries of Western Europe and Kievan Rus.

Test on the topic

Evaluation of the report

Average rating: 4.5. Total ratings received: 357.

The last (third) stage of the Middle Byzantine period covers the time from the accession of Alexios I Komnenos (1081) to the capture of Constantinople by the crusaders in 1204. This was the era of the Komnenos (1081-1185). Four of them left a deep mark on the history of Byzantium, and after the departure of the last, Andronikos I (1183-1185), the empire itself ceased to exist as a single state. The Comnenians were fully aware of the critical situation of their state and energetically, like zealous householders (they were blamed by their contemporaries for turning the empire into their fiefdom), took economic, social, and political measures to save it. They delayed the collapse of the empire, but were unable to strengthen its state system for a long time.

Agrarian relations. Economic and social policy of Komnenos. For the history of Byzantium in the 12th century. characterized by the manifestation of two opposing trends that emerged already in the 11th century. On the one hand, there was a rise in agricultural production (in modern historiography this time is referred to as the “era of economic expansion”), on the other, the process of political disintegration progressed. The prosperity of the economy not only led to the strengthening of the state system, but, on the contrary, accelerated its further decomposition. The traditional organization of power in the center and in the provinces, the previous forms of relations within the ruling class have objectively become an obstacle to further social development.

The Komnenians faced an intractable alternative: in order to consolidate central power and secure treasury revenue (a necessary condition for maintaining a strong army), they had to continue to protect small landownership and restrain the growth of large landownership, as well as the distribution of grants and privileges. But this kind of policy infringed on the interests of the military aristocracy, which brought them to power and remained their social support. The Komnenos (primarily Alexius I) tried to solve this problem in two ways, avoiding a radical breakdown of the socio-political system, which was considered an unshakable value. The thought of changes in “taxis” (the time-honored law and order) was alien to the mentality of the Byzantines. The introduction of innovations was considered a sin unforgivable by the emperor.

Firstly, Alexey I became less likely than his predecessors to grant individuals, churches and monasteries exemption from taxes and the right to settle peasants who were bankrupt and did not pay taxes to the treasury on their land as wigs. Grants of land from the state fund and from the estates of the ruling family into full ownership also became stingier. Secondly, Alexey I began to strictly condition the distribution of benefits and awards on personal connections and relationships. His favors were either a reward for service to the throne, or a guarantee for its performance, and preference was given to people who were personally devoted, first of all, to representatives of the vast Komnenos clan and families related to them.

The policy of the Komnenos could only bring temporary success - it suffered from internal contradictions: new forms of relations between representatives of the ruling class could become the basis for the revival of the state only with a radical restructuring of the centralized control system, but its strengthening remained the main goal. Moreover, the distribution of awards and privileges to comrades-in-arms led inevitably, no matter how devoted they were to the throne at the moment, to the growth of large landownership, the weakening of the free peasantry, a fall in tax revenues and the strengthening of the very centrifugal tendencies against which it was directed. The military aristocracy overpowered the bureaucratic nobility, but, having retained the previous system of power and central administrative apparatus, it needed the services of “bureaucrats” and, when carrying out its reforms, found itself hostage to them, limiting itself to half measures.

By the turn of the XI-XII centuries. A significant part of the peasantry found themselves in parikia. A large fiefdom has strengthened. By granting her master excussion (full or partial exemption from taxes), the emperor removed his possessions from the control of the fiscus. Immunity similar to Western European immunity was established: the patrimony of the court within the limits of his possessions, excluding the rights of higher jurisdiction associated with particularly serious crimes. Some patrimonial owners expanded the demenial economy, increased the production of grain, wine, and livestock, becoming involved in commodity-money relations. A considerable number of them, however, preferred to accumulate wealth, most of it from many noble persons and in the 12th century. they acquired not from the income of the estate, but from payments from the treasury and gifts from the emperor.

Wider Komnenos began to grant favors to the provinces, mainly on the terms of military service. Contemporaries compared pronia with benefice. Under Manuel I Komnenos (1143-1180), a fundamentally new type of pronia arose - not on the lands of the treasury, but on the private lands of free taxpayers. In other words, the emperors asserted the right of supreme ownership of the state to the lands of free peasants. Complained along with the right to appropriate state taxes, the right to manage the territory granted to the land contributed to the rapid transformation of conditional land ownership into full, hereditary property, and free taxpayers into the wigs of the owner of land, which in its social essence turned into private ownership.

In search of funds, Alexei I and his immediate successors resorted to a practice that was ruinous for free taxpayers - tax farming (having paid to the treasury an amount that exceeded the officially established amount from the tax district, the tax farmer more than compensated for the costs with the help of the authorities). Alexei I also encroached on the share of the clergy’s wealth. He confiscated the treasures of the church for the needs of the army and the ransom of prisoners, donated the possessions of those monasteries that were in decline to secular persons for management with the obligation to organize the management of the monasteries for the right to appropriate part of their income. He also carried out extraordinary audits of monastery lands, partially confiscating them, because the monks bought estates for next to nothing through corrupt officials and evaded paying taxes, not always having such a right.

Large patrimonies in the second half of the 12th century. began, in turn, to grant part of their possessions to their confidants, who became their “people.” Some magnates had large detachments of warriors, consisting, however, mainly not of vassals (fief relations in the empire remained poorly developed), but of numerous servants and mercenaries, strengthened their estates and introduced orders within them, similar to the capital's court. The deepening process of rapprochement between the social structure of the estate and that of Western Europe was also reflected in the morals of the nobility of the empire. New fashions penetrated from the West, tournaments began to be organized (especially under Manuel I), and the cult of knightly honor and military valor was established. If, of the 7 direct representatives of the Macedonian dynasty, only Vasily II was a warrior sovereign, then almost all of the Komnenos themselves led their army in battle. The power of the magnates began to extend to the territory of the surrounding area, often far beyond the borders of their own possessions. Centrifugal tendencies grew. An attempt to curb the willfulness of the magnates and the arbitrariness of officials was made by the usurper, Manuel I’s cousin, Andronikos I. He lowered taxes, abolished their tax farming, increased the salaries of provincial rulers, eradicated corruption and brutally suppressed the resistance of Manuel’s former comrades. The magnates rallied in hatred of Andronicus. Having taken away his throne and life as a result of a bloody coup, representatives of the landed aristocracy and the founders of the new Angels dynasty (1185-1204) practically eliminated the control of the central government over large landownership. Lands with free peasants were generously distributed throughout the country. The estates confiscated by Andronik were returned to their former owners. Taxes were raised again. By the end of the 12th century. a number of magnates of the Peloponnese, Thessaly, South Macedonia, and Asia Minor, having established their power in entire regions, refused to obey the central government. There was a threat of the collapse of the empire into independent principalities.

Byzantine city at the end of the 11th-12th centuries. Began in the 9th-10th centuries. the rise of crafts and trade led to the flourishing of provincial cities. The reform of the monetary system carried out by Alexei I, increasing the mass of small change coins necessary for retail trade turnover, and defining a clear relationship between coins of different denominations improved monetary circulation. Trade ties between the rural area and local city markets expanded and strengthened. In cities, near large monasteries and estates, fairs were periodically organized. Every autumn, merchants from all over the Balkan Peninsula and from other countries (including Rus') came to Thessalonica.

Unlike Western European ones, Byzantine cities were not under the jurisdiction of noble persons. They were ruled by the sovereign's governors, relying on garrisons, which then consisted mainly of mercenaries. With the fall in income from taxes from peasants, the importance of levies and duties from townspeople grew. Cities were deprived of any tax, trade, or political privileges. Attempts by the trade and craft elite to achieve more favorable conditions for their professional activities continued to be severely suppressed. Large patrimonial owners entered the city markets and started wholesale trade with other merchants. They acquired houses in cities for warehouses, shops, ships, piers, and increasingly traded without the mediation of city merchants. Foreign merchants, who received benefits from the emperor in exchange for military support, paid two to three times lower duties than Byzantine traders or did not pay them at all. The townspeople had to wage a difficult struggle with both the magnates and the state. The alliance of the central government with the cities against the rebellious magnates in Byzantium did not work out.

By the end of the 12th century. signs of impending decline were barely visible in the provincial centers, but clearly manifested themselves in the capital. The petty tutelage of the authorities, a system of restrictions, high taxes and duties, and conservative management principles stifled corporations. Crafts and trade in the capital of Hireli. Italian merchants found increasingly wider markets for their goods, which began to surpass Byzantine ones in quality, but were much cheaper than them.

International position of Byzantium. Alexei I seized power as a result of a military coup. From the first days of his reign, the new emperor had to overcome extreme difficulties. External enemies squeezed the empire in pincers: almost all of Asia Minor was in the hands of the Seljuk Turks, the Normans, having crossed from Italy to the Adriatic coast of the Balkans, captured the strategic fortress city of Dyrrhachium, and destroyed, defeating the troops of the empire, Epirus, Macedonia, and Thessaly. And at the gates of the capital there are Pechenegs. At first, Alexei I threw all his forces against the Normans. Only in 1085, with the help of Venice, whose merchants were granted rights

Duty-free trade in the Empire managed to push the Normans out of the Balkans.

Even more formidable was the danger from the nomads. The Pechenegs left after the raids across the Danube - they began to settle within the empire. They were supported by the Cumans, hordes of whom also invaded the peninsula. The Seljuks entered into negotiations with the Pechenegs on a joint attack on Constantinople. In desperation, the emperor turned to the sovereigns of the West, appealing for help and seriously seducing some circles of the West and played a role both in the organization of the First Crusade and in the subsequent claims of Western lords to the wealth of the empire. Meanwhile, Alexei I managed to incite hostility between the Pechenegs and the Cumans. In the spring of 1091, the Pecheneg horde was almost completely destroyed with the help of the Polovtsians in Thrace.

The diplomatic skill of Alexei I in his relations with the crusaders of the First Campaign helped him to return Nicaea with minimal costs, and then, after the victories of the Western knights over the Seljuks, mired in civil strife, to recapture the entire north-west of Asia Minor and the entire southern coast of the Black Sea. The position of the empire strengthened. The head of the Principality of Antioch, Bohemond of Tarentum, recognized Antioch as a fief of the Byzantine Empire.

The works of Alexios I were continued by his son John II Komnenos (1118-1143). In 1122, he defeated the Pechenegs, who again invaded Thrace and Macedonia, and forever eliminated the danger from them. Soon there was a clash with Venice, after John II deprived the Venetians who had settled in Constantinople and other cities of the empire of trade privileges. The Venetian fleet responded by ravaging the islands and coasts of Byzantium, and John II acquiesced, reaffirming the privileges of the republic. The Seljuks also remained dangerous. John II conquered the southern coast of Asia Minor from them. But the struggle for Syria and Palestine with the crusaders only weakened the empire. The power of Byzantium was strong only in Northern Syria.

In the middle of the 12th century. the center of the empire's foreign policy again moved to the Balkans. Manuel I (1143-1180) repelled a new onslaught of the Sicilian Normans on the Adriatic coast, about. Corfu, Thebes and Corinth, islands of the Aegean Sea. But attempts to transfer the war with them to Italy ended in failure. Nevertheless, Manuel subjugated Serbia, returned Dalmatia, and made the kingdom of Hungary a vassal. The victories cost a huge amount of effort and money. The strengthened Iconian (Rum) Sultanate of the Seljuk Turks renewed pressure on the eastern borders. In 1176 they completely defeated the army of Manuel I at Myriokephalos. The Empire was forced everywhere to go on the defensive.

The Empire on the Eve of the Catastrophe of 1204 The deterioration of the empire's position in the international arena and the death of Manuel I sharply aggravated the internal political situation. Power was completely seized by the court camarilla, headed by Maria of Antioch, the regent under the young Alexei II (1180-1183). The treasury was plundered. The arsenals and equipment of the navy were taken away. Maria openly patronized the Italians. The capital was seething with indignation. In 1182, an uprising broke out. The rebels dealt with the inhabitants of wealthy Italian neighborhoods, turning them into ruins. Both Maria and then Alexei II were killed.

Andronikos I, who came to power on the crest of the uprising, sought support among the craft and trading circles of Constantinople. He stopped the extortion and arbitrariness of officials, abolished the so-called “coastal law” - a custom that made it possible to rob shipwrecked merchant ships. Contemporaries report some revival of trade during the short reign of Andronikos. However, he was forced to partially compensate for the damage suffered by the Venetians in 1182 and restore their privileges. The international position of the empire worsened year by year: back in 1183. The Hungarians captured Dalmatia in 1184. Cyprus was laid aside. The highest nobility incited the growing discontent of the capital's residents and weaved intrigues. The disgraced nobles appealed for help to the Normans, and they actually invaded the Balkans again in 1185, captured Thessalonica and subjected it to merciless destruction. Andronik was blamed for everything. A conspiracy was hatched. Andronikos was seized and literally torn to pieces by a crowd on the streets of the city.

During the reign of Isaac II Angelos (1185-1195, 1203-1204) and his brother Alexei III (1195-1203), the process of decomposition of the central government apparatus progressed rapidly. The emperors were powerless to influence the course of events. In 1186 The Bulgarians threw off the power of the empire, forming the Second Bulgarian Kingdom, and in 1190 the Serbs became independent and revived their statehood. The empire was falling apart before our eyes. In the summer of 1203, the crusaders approached the walls of Constantinople, and Alexei III, refusing to lead the defense of the city, fled from the capital, which was in chaos, giving the throne to Isaac, who had previously been overthrown by him, to his son Alexei IV (1203-1204).

Feudal estate at the end of the 11th-12th centuries.

The formation of the main institutions of feudal society was completed in Byzantium at the end of the 11th - beginning of the 12th century. At this time, a feudal estate took shape in its main features and a significant mass of the previously free peasantry was turned into feudal dependent holders. Reflecting the interests of the feudal lords, the central government granted them increasingly broader privileges. They received “excussion” - full or partial exemption from taxes and the removal of their lands from the control of treasury officials. At the same time, the collection of taxes did not stop, but they were collected for his own benefit within the boundaries of his possessions by the patrimonial owner himself. Sometimes he also exercised the right of court in this territory. The state officially consolidated the current situation by issuing charters to the feudal lords with the right to collect court fees (excluding cases of particularly serious crimes) and thus granting the feudal lords judicial rights. The immunity of the feudal estate developed, in many ways similar to that of Western Europe.

There was no serfdom in Byzantium during this period. The emperor's domain and treasury lands were quite extensive, but much of them were not cultivated, and those that were cultivated were quickly reduced by grants. The income from these possessions could not become the main source of strength for the imperial power. The main funds of the state continued to consist of taxes from the free peasantry and the wigs of those feudal lords who did not have full excussion. Therefore, the central government was not interested in attaching these wigs to the land of the patrimonial owners.

Containing the decentralizing tendencies of the feudal lords and trying to “tie” them to the throne, the emperors began to grant them income from a certain territory inhabited by free peasants, and then these territories themselves, subject to service in favor of the state. In the 11th century these awards - pronias - consisted of transferring state lands to secular persons for management, and in the 12th century. The debate began to turn into a semblance of a Western European beneficiary, granted for life on the condition of performing primarily military service. But the debate soon showed a tendency to become a hereditary possession. Having originated as a means of strengthening central power, it became a means of strengthening the feudal lords, contributing to the feudal fragmentation of the country.

Both ordinary fiefdoms and proniars had their own military detachments, sometimes reaching up to a thousand soldiers. They had their own court, their own prison, bodyguards and numerous servants; They allocated some of their warriors to villages, and these small feudal lords performed military service for their lords. Thus, in Byzantium there appeared a tendency towards the creation of a feudal hierarchy similar to that of Western Europe.

Feudal city in the 11th-12th centuries.

Began in the 9th century. the rise of crafts and trade led to the 11th-12th centuries. to the flourishing of provincial cities. Economic ties within small areas were strengthened. Fairs and markets arose not only in cities, but also near large monasteries and secular estates, which increased the production of products for sale.

Unlike Western cities, Byzantine cities did not belong to individual feudal lords; they were under the authority of the state, which therefore did not seek an alliance with the townspeople. Since with the decline of the free peasantry, income from taxes from townspeople became increasingly important, the government did not give the cities any privileges; and although the trade and craft elite of the cities, as in the West, tried to defend their interests, the state actively opposed their desire to independently manage the life of the city. The city was ruled by a strategist appointed by the emperor, whose troops often consisted of mercenaries.

In such conditions, the feudal lords strengthened their positions in the city. Here they acquired houses, farmsteads, warehouses, shops, piers, ships, and themselves, without the mediation of local merchants, sold the products of their estates. From the end of the 11th century. The emperors began to widely resort to military assistance from the Italian republics (Venice, Genoa, Pisa), granting them numerous privileges for this and, above all, the right to duty-free trade in the largest cities of the empire. The feudal lords launched a wide wholesale trade with foreigners, who paid more than local merchants, who were forced to pay high duties and taxes to the treasury.

Thus, the townspeople had to fight not directly with the feudal lords, but with the state. Placed in extremely unfavorable conditions, Byzantine cities could not withstand competition with foreigners. At the end of the 12th century. the symptoms of the impending decline were still quite weak in provincial cities, but in the capital they progressed rapidly from the beginning of the 12th century. The conservative system of management of craft and trade corporations, petty tutelage on the part of the state, high taxes - all this hindered the growth of urban crafts and trade, which gradually fell into decline. Italian traders brought more and more foreign handicrafts, which were cheaper than Byzantine ones, and soon surpassed them in quality.

Foreign policy of the empire under the Comneni

The accession to the throne of Alexios I Komnenos (1081-1118) meant the victory of the landowning feudal nobility over the bureaucratic aristocracy. The situation of the empire was extremely difficult. The Seljuk Turks took almost all of Asia Minor from Byzantium. The Normans, having conquered the last possessions of the empire in Italy, landed in 1081 on the Adriatic coast and captured an important strategic point - Dyrrachium (Drach). They plundered Epirus, Macedonia and Thessaly. In the fight against the Normans, Alexei Komnin suffered defeats. Only in 1085, calling on Venice for help, for which the Venetian merchants received great trading privileges, did the emperor achieve the departure of the Normans from the Balkan Peninsula.

But then an even more serious danger arose. The Pechenegs, who had previously made short-term raids and usually returned across the Danube, began to spend the winter within the empire. Alexei's campaign against them ended in the complete defeat of his army. The Pechenegs were helped by the Polovtsians, hordes of whom also invaded the empire. The Turks entered into negotiations with the Pechenegs about joint actions against Constantinople. The desperate emperor turned to the West with a request for military assistance. He managed to push the Polovtsy and Pechenegs together. In the spring of 1091; The Pecheneg horde was almost completely destroyed. With the help of diplomacy, Alexey returned Nicaea during the First Crusade, and then, using the victories of Western European knights and the civil strife of the Seljuk Turks, he reconquered the entire north-west of Asia Minor and the southern coast of the Black Sea. The position of the empire was significantly strengthened. The head of the Antioch Crusader Principality, Bohemond of Tarentum, recognized himself as a vassal of Byzantium.

In 1122, new hordes of Pechenegs ravaged Thrace and Macedonia, but John II Komnenos (1118-1143) managed to defeat the nomads. By this time, the Venetian merchants were firmly established in Constantinople and other Byzantine cities. The attempt to deprive the Venetians of privileges unfavorable for the empire was unsuccessful. The Venetian fleet devastated the islands and coast and forced the emperor to confirm the benefits given to him by Alexei I. The main danger threatened Byzantium from the East. In the fight against the Seljuk Turks, the empire recaptured the southern coast of the Asia Minor Peninsula, but the wars with the crusaders for Syria and Palestine only weakened the country. Only in Northern Syria did the empire maintain a strong position.

From the middle of the 12th century. the center of gravity of Byzantine foreign policy was transferred to Europe. The Empire repelled the new invasion of the Sicilian Normans on the Adriatic coast, the island of Corfu, Corinth, Thebes and the islands of the Aegean Sea. The attempt of Manuel I Komnenos (1143-1180) to transfer the war with the Normans to Italy ended in defeat. However, Manuel managed to establish his power in Serbia, return Dalmatia and place Hungary in vassal dependence on Byzantium. But the empire's forces were exhausted. In 1176, Manuel was completely defeated at Myriocephalus by the Seljuk Turks of the Iconian (Rum) Sultanate (Asia Minor). The empire was forced to go on the defensive on all its borders.

At the end of the 12th century. The situation within the empire was extremely unstable: there was an intense struggle for power, accompanied by frequent palace coups.

After the death of Manuel I, power fell into the hands of the court camarilla, headed by the regent of the young Alexei II - Maria of Antioch. The new rulers plundered the treasury and openly patronized the Italians, from whom they sought support. The capital was seething with indignation.

In 1182, the rebellious people reduced the rich Italian (“Latin”) quarters of Constantinople to ruins. Taking advantage of the popular uprising, power was seized by a representative of the Komnenos side line - Andronikos I Komnenos (1183-1185).

In the fight against the large feudal lords, against whose will he came to power, Andronik sought to rely on small landowners and gain the support of the merchants. He abolished coastal law, according to which large feudal lords could seize the cargo of ships in distress off the coast of their possessions. To curb the arbitrariness of officials, tax collection was streamlined. The sale of positions was prohibited. Contemporaries speak of a noticeable revival of crafts and trade at this time and of some improvement in the situation of the peasantry.

But Andronicus’s reforms left the entire existing system of the feudal state intact. Taxes remained very high. In order for officials to stop extortion, they were given exorbitantly high salaries. The Italians were not expelled. Even the privileges of the Venetians, abolished by Manuel in 1171, were restored. The merchants of Constantinople expressed dissatisfaction; The metropolitan aristocracy and provincial nobility raised uprising after uprising against the emperor. Andronik responded with unheard-of terror - mass executions began. Warring factions of large feudal lords united against the emperor. They called on the Sicilian king for help. In 1185, the Sicilian Normans took Thessalonica and devastated it. A conspiracy was drawn up against Andronicus. He was captured, tortured and executed.

Isaac II Angelos (1185-1195) seized power. Under him, all Andronicus' innovations were canceled. The confiscated possessions of the great nobility were returned. The remnants of lands with a free population were generously distributed. Tax burden has increased even more. The emperor lavished his treasury on feasts and entertainment. Bribery flourished. The empire lost one region after another. Back in 1183, the Hungarians captured Dalmatia, in 1184 Cyprus seceded, in 1185 Northern Bulgaria was liberated, and in 1187 the independence of the Bulgarian state was recognized by Byzantium.

In the mid-90s, the largest feudal lords of Macedonia refused to obey the emperor. In 1190, Byzantium had to recognize the independence of the Serbian state, which had formed back in the 10th century. and from the beginning of XI that. dependent on Byzantium. Trebizond declared itself independent. Feudal unrest flared up again. Isaac II was overthrown and blinded by his brother Alexios III (1195-1203).

The last (third) stage of the Middle Byzantine period covers the time from the accession of Alexios I Komnenos (1081) to the capture of Constantinople by the crusaders in 1204. This was the era of the Komnenos (1081-1185). Four of them left a deep mark on the history of Byzantium, and after the departure of the last, Andronikos I (1183-1185), the empire itself ceased to exist as a single state. The Comnenians were fully aware of the critical situation of their state and energetically, like zealous householders (they were blamed by their contemporaries for turning the empire into their fiefdom), took economic, social, and political measures to save it. They delayed the collapse of the empire, but were unable to strengthen its state system for a long time.

Agrarian relations. Economic and social policy of Komnenos. For the history of Byzantium in the 12th century. characterized by the manifestation of two opposing trends that emerged already in the 11th century. On the one hand, there was a rise in agricultural production (in modern historiography this time is referred to as the “epoch of economic expansion”), on the other hand, the process of political disintegration progressed. The prosperity of the economy not only led to the strengthening of the state system, but, on the contrary, accelerated its further decomposition. The traditional organization of power in the center and in the provinces, the previous forms of relations within the ruling class have objectively become an obstacle to further social development.

The Komnenians faced an intractable alternative: in order to consolidate central power and secure treasury revenue (a necessary condition for maintaining a strong army), they had to continue to protect small landownership and restrain the growth of large landownership, as well as the distribution of grants and privileges. But this kind of policy infringed on the interests of the military aristocracy, which brought them to power and remained their social support. The Komnenos (primarily Alexius I) tried to solve this problem in two ways, avoiding a radical breakdown of the socio-political system, which was considered an unshakable value. The thought of changes in “taxis” (the time-honored law and order) was alien to the mentality of the Byzantines. The introduction of innovations was considered a sin unforgivable by the emperor.

Firstly, Alexey I became less likely than his predecessors to grant individuals, churches and monasteries exemption from taxes and the right to settle peasants who were bankrupt and did not pay taxes to the treasury on their land as wigs. Grants of land from the state fund and from the estates of the ruling family into full ownership also became stingier. Secondly, Alexey I began to strictly condition the distribution of benefits and awards on personal connections and relationships. His favors were either a reward for service to the throne, or a guarantee for its performance, and preference was given to people who were personally devoted, first of all, to representatives of the vast Komnenos clan and families related to them.

The policy of the Komnenos could only bring temporary success - it suffered from internal contradictions: new forms of relations between representatives of the ruling class could become the basis for the revival of the state only with a radical restructuring of the centralized control system, but its strengthening remained the main goal. Moreover, the distribution of awards and privileges to comrades-in-arms led inevitably, no matter how devoted they were to the throne at the moment, to the growth of large landownership, the weakening of the free peasantry, a fall in tax revenues and the strengthening of the very centrifugal tendencies against which it was directed. The military aristocracy overpowered the bureaucratic nobility, but, having retained the previous system of power and central administrative apparatus, it needed the services of “bureaucrats” and, when carrying out its reforms, found itself hostage to them, limiting itself to half measures.

By the turn of the XI-XII centuries. A significant part of the peasantry found themselves in parikia. A large fiefdom has strengthened. By granting her master excussion (full or partial exemption from taxes), the emperor removed his possessions from the control of the fiscus. Immunity similar to Western European immunity was established: the patrimony of the court within the limits of his possessions, excluding the rights of higher jurisdiction associated with particularly serious crimes. Some patrimonial owners expanded the demenial economy, increased the production of grain, wine, and livestock, becoming involved in commodity-money relations. A considerable number of them, however, preferred to accumulate wealth, most of it from many noble persons and in the 12th century. they acquired not from the income of the estate, but from payments from the treasury and gifts from the emperor.

Wider Komnenos began to grant favors to the provinces, mainly on the terms of military service. Contemporaries compared pronia with benefice. Under Manuel I Komnenos (1143-1180), a fundamentally new type of pronia arose - not on the lands of the treasury, but on the private lands of free taxpayers. In other words, the emperors asserted the right of supreme ownership of the state to the lands of free peasants. Complained along with the right to appropriate state taxes, the right to manage the territory granted to the land contributed to the rapid transformation of conditional land ownership into full, hereditary property, and free taxpayers into the wigs of the owner of land, which in its social essence turned into private ownership.

In search of funds, Alexei I and his immediate successors resorted to a practice that was ruinous for free taxpayers - tax farming (having paid to the treasury an amount that exceeded the officially established amount from the tax district, the tax farmer more than compensated for the costs with the help of the authorities). Alexei I also encroached on the share of the clergy’s wealth. He confiscated the treasures of the church for the needs of the army and the ransom of prisoners, donated the possessions of those monasteries that were in decline to secular persons for management with the obligation to organize the management of the monasteries for the right to appropriate part of their income. He also carried out extraordinary audits of monastery lands, partially confiscating them, because the monks bought estates for next to nothing through corrupt officials and evaded paying taxes, not always having such a right.

Large patrimonies in the second half of the 12th century. began, in turn, to grant part of their possessions to their confidants, who became their “people.” Some magnates had large detachments of warriors, consisting, however, mainly not of vassals (fief relations in the empire remained poorly developed), but of numerous servants and mercenaries, strengthened their estates and introduced orders within them, similar to the capital's court. The deepening process of rapprochement between the social structure of the estate and that of Western Europe was also reflected in the morals of the nobility of the empire. New fashions penetrated from the West, tournaments began to be organized (especially under Manuel I), and the cult of knightly honor and military valor was established. If, of the 7 direct representatives of the Macedonian dynasty, only Vasily II was a warrior sovereign, then almost all of the Komnenos themselves led their army in battle. The power of the magnates began to extend to the territory of the surrounding area, often far beyond the borders of their own possessions. Centrifugal tendencies grew. An attempt to curb the willfulness of the magnates and the arbitrariness of officials was made by the usurper, Manuel I’s cousin, Andronikos I. He lowered taxes, abolished their tax farming, increased the salaries of provincial rulers, eradicated corruption and brutally suppressed the resistance of Manuel’s former comrades. The magnates rallied in hatred of Andronicus. Having taken away his throne and life as a result of a bloody coup, representatives of the landed aristocracy and the founders of the new Angels dynasty (1185-1204) practically eliminated the control of the central government over large landownership. Lands with free peasants were generously distributed throughout the country. The estates confiscated by Andronik were returned to their former owners. Taxes were raised again. By the end of the 12th century. a number of magnates of the Peloponnese, Thessaly, South Macedonia, and Asia Minor, having established their power in entire regions, refused to obey the central government. There was a threat of the collapse of the empire into independent principalities.

Byzantine city at the end of the 11th-12th centuries. Began in the 9th-10th centuries. the rise of crafts and trade led to the flourishing of provincial cities. The reform of the monetary system carried out by Alexei I, increasing the mass of small change coins necessary for retail trade turnover, and defining a clear relationship between coins of different denominations improved monetary circulation. Trade ties between the rural area and local city markets expanded and strengthened. In cities, near large monasteries and estates, fairs were periodically organized. Every autumn, merchants from all over the Balkan Peninsula and from other countries (including Rus') came to Thessalonica.

Unlike Western European ones, Byzantine cities were not under the jurisdiction of noble persons. They were ruled by the sovereign's governors, relying on garrisons, which then consisted mainly of mercenaries. With the fall in income from taxes from peasants, the importance of levies and duties from townspeople grew. Cities were deprived of any tax, trade, or political privileges. Attempts by the trade and craft elite to achieve more favorable conditions for their professional activities continued to be severely suppressed. Large patrimonial owners entered the city markets and started wholesale trade with other merchants. They acquired houses in cities for warehouses, shops, ships, piers, and increasingly traded without the mediation of city merchants. Foreign merchants, who received benefits from the emperor in exchange for military support, paid two to three times lower duties than Byzantine traders or did not pay them at all. The townspeople had to wage a difficult struggle with both the magnates and the state. The alliance of the central government with the cities against the rebellious magnates in Byzantium did not work out.

By the end of the 12th century. signs of impending decline were barely visible in the provincial centers, but clearly manifested themselves in the capital. The petty tutelage of the authorities, a system of restrictions, high taxes and duties, and conservative management principles stifled corporations. Crafts and trade in the capital of Hireli. Italian merchants found increasingly wider markets for their goods, which began to surpass Byzantine ones in quality, but were much cheaper than them.

International position of Byzantium. Alexei I seized power as a result of a military coup. From the first days of his reign, the new emperor had to overcome extreme difficulties. External enemies squeezed the empire in pincers: almost all of Asia Minor was in the hands of the Seljuk Turks, the Normans, having crossed from Italy to the Adriatic coast of the Balkans, captured the strategic fortress city of Dyrrhachium, and destroyed, defeating the troops of the empire, Epirus, Macedonia, and Thessaly. And at the gates of the capital there are Pechenegs. At first, Alexei I threw all his forces against the Normans. Only in 1085, with the help of Venice, whose merchants were granted rights

Duty-free trade in the Empire managed to push the Normans out of the Balkans.

Even more formidable was the danger from the nomads. The Pechenegs left after the raids across the Danube - they began to settle within the empire. They were supported by the Cumans, hordes of whom also invaded the peninsula. The Seljuks entered into negotiations with the Pechenegs on a joint attack on Constantinople. In desperation, the emperor turned to the sovereigns of the West, appealing for help and seriously seducing some circles of the West and played a role both in the organization of the First Crusade and in the subsequent claims of Western lords to the wealth of the empire. Meanwhile, Alexei I managed to incite hostility between the Pechenegs and the Cumans. In the spring of 1091, the Pecheneg horde was almost completely destroyed with the help of the Polovtsians in Thrace.

The diplomatic skill of Alexei I in his relations with the crusaders of the First Campaign helped him to return Nicaea with minimal costs, and then, after the victories of the Western knights over the Seljuks, mired in civil strife, to recapture the entire north-west of Asia Minor and the entire southern coast of the Black Sea. The position of the empire strengthened. The head of the Principality of Antioch, Bohemond of Tarentum, recognized Antioch as a fief of the Byzantine Empire.

The works of Alexios I were continued by his son John II Komnenos (1118-1143). In 1122, he defeated the Pechenegs, who again invaded Thrace and Macedonia, and forever eliminated the danger from them. Soon there was a clash with Venice, after John II deprived the Venetians who had settled in Constantinople and other cities of the empire of trade privileges. The Venetian fleet responded by ravaging the islands and coasts of Byzantium, and John II acquiesced, reaffirming the privileges of the republic. The Seljuks also remained dangerous. John II conquered the southern coast of Asia Minor from them. But the struggle for Syria and Palestine with the crusaders only weakened the empire. The power of Byzantium was strong only in Northern Syria.

In the middle of the 12th century. the center of the empire's foreign policy again moved to the Balkans. Manuel I (1143-1180) repelled a new onslaught of the Sicilian Normans on the Adriatic coast, about. Corfu, Thebes and Corinth, islands of the Aegean Sea. But attempts to transfer the war with them to Italy ended in failure. Nevertheless, Manuel subjugated Serbia, returned Dalmatia, and made the kingdom of Hungary a vassal. The victories cost a huge amount of effort and money. The strengthened Iconian (Rum) Sultanate of the Seljuk Turks renewed pressure on the eastern borders. In 1176 they completely defeated the army of Manuel I at Myriokephalos. The Empire was forced everywhere to go on the defensive.

The Empire on the Eve of the Catastrophe of 1204 The deterioration of the empire's position in the international arena and the death of Manuel I sharply aggravated the internal political situation. Power was completely seized by the court camarilla, headed by Maria of Antioch, the regent under the young Alexei II (1180-1183). The treasury was plundered. The arsenals and equipment of the navy were taken away. Maria openly patronized the Italians. The capital was seething with indignation. In 1182, an uprising broke out. The rebels dealt with the inhabitants of wealthy Italian neighborhoods, turning them into ruins. Both Maria and then Alexei II were killed.

Andronikos I, who came to power on the crest of the uprising, sought support among the craft and trading circles of Constantinople. He stopped the extortion and arbitrariness of officials, abolished the so-called “coastal law” - a custom that made it possible to rob shipwrecked merchant ships. Contemporaries report some revival of trade during the short reign of Andronikos. However, he was forced to partially compensate for the damage suffered by the Venetians in 1182 and restore their privileges. The international position of the empire worsened year by year: back in 1183. The Hungarians captured Dalmatia in 1184. Cyprus was laid aside. The highest nobility incited the growing discontent of the capital's residents and weaved intrigues. The disgraced nobles appealed for help to the Normans, and they actually invaded the Balkans again in 1185, captured Thessalonica and subjected it to merciless destruction. Andronik was blamed for everything. A conspiracy was hatched. Andronikos was seized and literally torn to pieces by a crowd on the streets of the city.

During the reign of Isaac II Angelos (1185-1195, 1203-1204) and his brother Alexei III (1195-1203), the process of decomposition of the central government apparatus progressed rapidly. The emperors were powerless to influence the course of events. In 1186 The Bulgarians threw off the power of the empire, forming the Second Bulgarian Kingdom, and in 1190 the Serbs became independent and revived their statehood. The empire was falling apart before our eyes. In the summer of 1203, the crusaders approached the walls of Constantinople, and Alexei III, refusing to lead the defense of the city, fled from the capital, which was in chaos, giving the throne to Isaac, who had previously been overthrown by him, to his son Alexei IV (1203-1204).

The end has come. But even at the beginning of the 4th century. the center of power moved to the calmer and richer eastern, Balkan and Asia Minor provinces. Soon the capital became Constantinople, founded by Emperor Constantine on the site of the ancient Greek city of Byzantium. True, the West also had its own emperors - the administration of the empire was divided. But it was the sovereigns of Constantinople who were considered the eldest. In the 5th century The Eastern, or Byzantine, as they said in the West, empire withstood the attack of the barbarians. Moreover, in the VI century. its rulers conquered many lands of the West occupied by the Germans and held them for two centuries. Then they were Roman emperors not only in title, but also in essence. Having lost by the 9th century. a significant part of the Western possessions, Byzantine Empire nevertheless, she continued to live and develop. It lasted up to 1453 g., when the last stronghold of her power, Constantinople, fell under the pressure of the Turks. All this time, the empire remained the legitimate successor in the eyes of its subjects. Its inhabitants called themselves Romans, which means “Romans” in Greek, although the majority of the population was Greek.

The geographical position of Byzantium, which spread its possessions over two continents - Europe and Asia, and sometimes extended its power to areas of Africa, made this empire a kind of connecting link between East and West. The constant bifurcation between the Eastern and Western worlds became the historical destiny of the Byzantine Empire. The mixture of Greco-Roman and Eastern traditions left its mark on public life, statehood, religious and philosophical ideas, culture and art of Byzantine society. However, Byzantium went on its own historically, in many ways different from the destinies of the countries of both the East and the West, which also determined the features of its culture.

Map of the Byzantine Empire

History of the Byzantine Empire

The culture of the Byzantine Empire was created by many peoples. In the first centuries of the existence of the Roman Empire, all the eastern provinces of Rome were under the rule of its emperors: Balkan Peninsula, Asia Minor, southern Crimea, Western Armenia, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, northeastern Libya. The creators of the new cultural unity were the Romans, Armenians, Syrians, Egyptian Copts and barbarians who settled within the borders of the empire.

The most powerful cultural layer in this cultural diversity was the ancient heritage. Long before the advent of the Byzantine Empire, thanks to the campaigns of Alexander the Great, all the peoples of the Middle East were subjected to the powerful unifying influence of ancient Greek, Hellenic culture. This process was called Hellenization. Migrants from the West also adopted Greek traditions. So the culture of the renewed empire developed as a continuation mainly of the ancient Greek culture. The Greek language already in the 7th century. reigned supreme in the written and oral speech of the Romans (Romans).

The East, unlike the West, did not experience devastating barbarian raids. Therefore, there was no terrible cultural decline here. Most ancient Greco-Roman cities continued to exist in the Byzantine world. In the first centuries of the new era, they retained their previous appearance and structure. As in Hellas, the heart of the city remained the agora - a vast square where public meetings were previously held. Now, however, people increasingly gathered at the hippodrome - the place of performances and races, the announcement of decrees and public executions. The city was decorated with fountains and statues, magnificent houses of the local nobility and public buildings. In the capital - Constantinople - the best craftsmen erected monumental palaces of the emperors. The most famous of the early ones - the Great Imperial Palace of Justinian I, the famous conqueror of the Germans, who ruled in 527-565 - was erected above the Sea of Marmara. The appearance and decoration of the capital's palaces were reminiscent of the times of the ancient Greco-Macedonian rulers of the Middle East. But the Byzantines also used Roman urban planning experience, in particular the water supply system and baths (therms).

Most of the large cities of antiquity remained centers of trade, crafts, science, literature and art. Such were Athens and Corinth in the Balkans, Ephesus and Nicaea in Asia Minor, Antioch, Jerusalem and Berit (Beirut) in Syro-Palestines, Alexandria in ancient Egypt.

The collapse of many Western cities led to a shift of trade routes to the east. At the same time, barbarian invasions and captures made land roads unsafe. Law and order were preserved only in the domains of the Constantinople emperors. Therefore, the “dark” centuries filled with wars (V-VIII centuries) sometimes became heyday of Byzantine ports. They served as transit points for military detachments going to numerous wars, and as anchorages for the Byzantine fleet, the strongest in Europe. But the main meaning and source of their existence was maritime trade. The trade ties of the Romans extended from India to Britain.

Ancient crafts continued to develop in cities. Many products of early Byzantine masters are real works of art. The masterpieces of Roman jewelers - made of precious metals and stones, colored glass and ivory - aroused admiration in the countries of the Middle East and barbaric Europe. The Germans, Slavs, and Huns adopted the skills of the Romans and imitated them in their own creations.

Coins in the Byzantine Empire

For a long time, only Roman coins circulated throughout Europe. The emperors of Constantinople continued minting Roman money, making only minor changes to its appearance. The right of the Roman emperors to rule was not questioned even by their fierce enemies, and the only mint in Europe was proof of this. The first in the West who dared to start minting his own coin was the Frankish king in the second half of the 6th century. However, even then the barbarians only imitated the Roman example.

Legacy of the Roman Empire

The Roman heritage of Byzantium can be traced even more noticeably in the system of government. Politicians and philosophers of Byzantium never tired of repeating that Constantinople is the New Rome, that they themselves are Romans, and their power is the only empire preserved by God. The extensive apparatus of the central government, the tax system, and the legal doctrine of the inviolability of the imperial autocracy were preserved without fundamental changes.

The life of the emperor, furnished with extraordinary pomp, and admiration for him were inherited from the traditions of the Roman Empire. In the late Roman period, even before the Byzantine era, palace rituals included many elements of eastern despotism. Basileus, the emperor, appeared before the people only accompanied by a brilliant retinue and an impressive armed guard, following in a strictly defined order. They prostrated themselves before the basileus, during the speech from the throne he was covered with special curtains, and only a few were given the right to sit in his presence. Only the highest ranks of the empire were allowed to eat at his meal. The reception of foreign ambassadors, whom the Byzantines tried to impress with the greatness of the emperor's power, was especially pompous.

The central administration was concentrated in several secret departments: the Schwaz department of the logothet (manager) of the henikon - the main tax institution, the department of the military treasury, the department of post and external relations, the department for managing the property of the imperial family, etc. In addition to the staff of officials in the capital, each department had officials sent on temporary assignments to the provinces. There were also palace secrets that controlled the institutions that directly served the royal court: food stores, dressing rooms, stables, repairs.

Byzantium retained Roman law and the basics of Roman legal proceedings. In the Byzantine era, the development of the Roman theory of law was completed, such theoretical concepts of jurisprudence as law, law, custom were finalized, the difference between private and public law was clarified, the foundations for regulating international relations, the norms of criminal law and procedure were determined.

The legacy of the Roman Empire was a clear tax system. A free city dweller or peasant paid taxes and duties to the treasury on all types of his property and on any kind of labor activity. He paid for the ownership of the land, and for the garden in the city, and for the mule or sheep in the barn, and for the rented premises, and for the workshop, and for the shop, and for the ship, and for the boat. Almost no product on the market changed hands without the watchful eye of officials.

Warfare

Byzantium also preserved the Roman art of waging “correct war.” The empire carefully preserved, copied and studied ancient strategikons - treatises on the art of war.

Periodically, the authorities reformed the army, partly due to the emergence of new enemies, partly to suit the capabilities and needs of the state itself. The basis of the Byzantine army became cavalry. Its number in the army ranged from 20% in late Roman times to more than one third in the 10th century. An insignificant part, but very combat-ready, became the cataphracts - heavy cavalry.

Navy Byzantium was also a direct inheritance of Rome. The following facts speak about his strength. In the middle of the 7th century. Emperor Constantine V was able to send 500 ships to the mouth of the Danube to conduct military operations against the Bulgarians, and in 766 - even over 2 thousand. The largest ships (dromons) with three rows of oars took on board up to 100-150 soldiers and about the same number oarsmen

An innovation in the fleet was "Greek fire"- a mixture of petroleum, flammable oils, sulfur asphalt, - invented in the 7th century. and terrified enemies. He was thrown out of siphons arranged in the form of bronze monsters with gaping mouths. The siphons could be turned in different directions. The ejected liquid ignited spontaneously and burned even in water. It was with the help of “Greek fire” that the Byzantines repulsed two Arab invasions - in 673 and 718.

Military construction was excellently developed in the Byzantine Empire, based on a rich engineering tradition. Byzantine engineers - builders of fortresses were famous far beyond the borders of the country, even in distant Khazaria, where a fortress was built according to their plans

Large coastal cities, in addition to walls, were protected by underwater piers and massive chains that blocked the enemy fleet from entering the bays. Such chains closed the Golden Horn in Constantinople and the Gulf of Thessalonica.

For the defense and siege of fortresses, the Byzantines used various engineering structures (ditches and palisades, mines and embankments) and all kinds of weapons. Byzantine documents mention battering rams, movable towers with walkways, stone-throwing ballistae, hooks for capturing and destroying enemy siege equipment, cauldrons from which boiling tar and molten lead were poured onto the heads of the besiegers.